WASF.

There is nothing they can do about it.

It may sound defeatist, but it's the honest truth.

WASF.

The train has left the station.

There hasn't been this much CO2 in the atmosphere in millions of years.

We can't stop putting it in the atmosphere.

We certainly can't capture it back out of the atmosphere and safely store it at the pace or scale we've been putting it up there.

I've been suffering from anxiety and depression for a decade.

Why burden them with my knowledge?

I would if it would serve a purpose.

My kids' futures are going to be severely compromised by what we are doing to our biosphere, I might as well at least allow them to enjoy their present.

Fortunately, at least we already live in Canada... one of the best-positioned countries to adapt to the new climate realities we will face.

On the plus side: huge territory; low population; plenty of water.

On the minus side: a ruthless empire on our border, one that will need not just more water but also more arable land (in the new climate conditions of the future) and has the military means to take what they want.

Alas, that problem of Canada's (becoming officially the 51st state) will have to be dealt with as best we can at a later date.

For now, I've decided to not encumber my kids with the distress that other kids are experiencing.

(they are well aware of my significant concern about climate change, and that it is a significant factor contributing to my on-going mental health issues; what they don't know is that I have concluded WASF, that billions are going to die, that we will be lucky not to cause our own extinction, and that if we do escape that fate, it will only be by virtue of some # of millions, perhaps, certainly not billions, finding some way to survive at the poles.)

Climate-Alarmist Parents Warned Not To Cause 'Eco-Anxiety' By Terrifying Children. zerohedge. Sept. 20, 2019.

Climate activist parents are freaking out their kids, according to a group of psychologists working with the University of Bath - who say they are receiving a growing number of cases in which children are 'terrified' of climate catastrophe and have "eco-anxiety.

According to The Telegraph, "Protests by groups such as Extinction Rebellion, the recent fires in the Amazon and apocalyptic warnings by the teenage activist Greta Thunberg have prompted a "tsunami" of young people seeking help.

"A lot of parents are coming into therapy asking for help with the children and it has escalated a lot this summer," said Bath teaching fellow and CPA executive Caroline Hickman.

The symptoms are the same [as clinical anxiety], the feelings are the same, but the cause is different," she added. "The fear is of environmental doom - that we’re all going to die."

Climate activist parents are freaking out their kids, according to a group of psychologists working with the University of Bath - who say they are receiving a growing number of cases in which children are 'terrified' of climate catastrophe and have "eco-anxiety.

There is nothing they can do about it.

It may sound defeatist, but it's the honest truth.

WASF.

The train has left the station.

There hasn't been this much CO2 in the atmosphere in millions of years.

We can't stop putting it in the atmosphere.

We certainly can't capture it back out of the atmosphere and safely store it at the pace or scale we've been putting it up there.

I've been suffering from anxiety and depression for a decade.

Why burden them with my knowledge?

I would if it would serve a purpose.

My kids' futures are going to be severely compromised by what we are doing to our biosphere, I might as well at least allow them to enjoy their present.

Fortunately, at least we already live in Canada... one of the best-positioned countries to adapt to the new climate realities we will face.

On the plus side: huge territory; low population; plenty of water.

On the minus side: a ruthless empire on our border, one that will need not just more water but also more arable land (in the new climate conditions of the future) and has the military means to take what they want.

Alas, that problem of Canada's (becoming officially the 51st state) will have to be dealt with as best we can at a later date.

For now, I've decided to not encumber my kids with the distress that other kids are experiencing.

(they are well aware of my significant concern about climate change, and that it is a significant factor contributing to my on-going mental health issues; what they don't know is that I have concluded WASF, that billions are going to die, that we will be lucky not to cause our own extinction, and that if we do escape that fate, it will only be by virtue of some # of millions, perhaps, certainly not billions, finding some way to survive at the poles.)

Climate-Alarmist Parents Warned Not To Cause 'Eco-Anxiety' By Terrifying Children. zerohedge. Sept. 20, 2019.

Climate activist parents are freaking out their kids, according to a group of psychologists working with the University of Bath - who say they are receiving a growing number of cases in which children are 'terrified' of climate catastrophe and have "eco-anxiety.

According to The Telegraph, "Protests by groups such as Extinction Rebellion, the recent fires in the Amazon and apocalyptic warnings by the teenage activist Greta Thunberg have prompted a "tsunami" of young people seeking help.

A group of psychologists working with the University of Bath says it is receiving a growing volume of enquiries from teachers, doctors and therapists unable to cope.

The Climate Psychology Alliance (CPA) told The Daily Telegraph some children complaining of eco-anxiety have even been given psychiatric drugs.

The body is campaigning for anxiety specifically caused by fear for the future of the planet to be recognised as a psychological phenomenon.

However, they do not want it classed as a mental illness because, unlike standard anxiety, the cause of the worry is “rational”. -The Telegraph

"A lot of parents are coming into therapy asking for help with the children and it has escalated a lot this summer," said Bath teaching fellow and CPA executive Caroline Hickman.

The symptoms are the same [as clinical anxiety], the feelings are the same, but the cause is different," she added. "The fear is of environmental doom - that we’re all going to die."

Climate activist parents are freaking out their kids, according to a group of psychologists working with the University of Bath - who say they are receiving a growing number of cases in which children are 'terrified' of climate catastrophe and have "eco-anxiety.

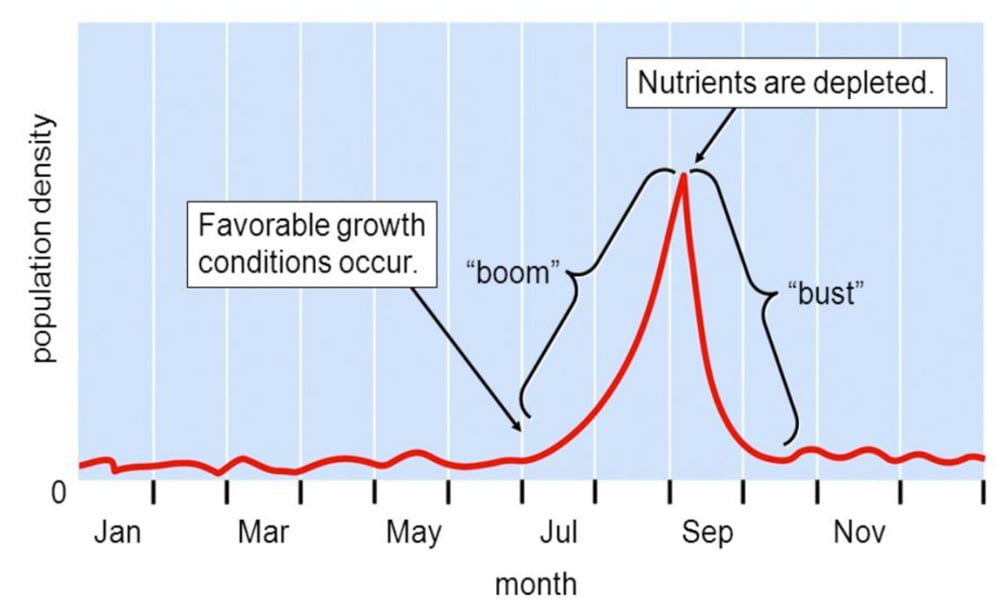

The ‘boom-bust’ population cycle. Note the resemblance of the human population growth curve in Fig. 1 to the exponential ‘boom’ phase of the cycle. The world community can still choose to influence the speed and depth of the coming bust phase. Source of graph:Biology: Life on Earth, 8th ed., Fig. 26-3.

The ‘boom-bust’ population cycle. Note the resemblance of the human population growth curve in Fig. 1 to the exponential ‘boom’ phase of the cycle. The world community can still choose to influence the speed and depth of the coming bust phase. Source of graph:Biology: Life on Earth, 8th ed., Fig. 26-3.