An insightful quote from Mark Twain says:

It is easier to fool people than it is to convince them that they have been fooled.

What often happens, in fact, is that people on opposite sides of an issue suspect (or are convinced) that the other side has been brainwashed. Sometimes one side is more justified in the charge than the other, in which case the brainwashed victims effectively assert a sort of projected symmetry that rings false.

Bi-directional allegations of brainwashing show up in the context of COVID: masks provide a clear means of identifying either those (masked individuals) who have been fooled into controlled submission to believe that the pandemic is real and deadly vs. those (unmasked fighters for freedom) who have been sadly misled to think it’s all a hoax and in so doing endanger us all. Each side may feel anger or pity toward the other. Climate change is similar: its denial has become an article of faith for the brainwashed non-believers, who accuse the gullible believers of being brainwashed by self-serving scientists vying for funding, power, or something (cake, maybe?).

To either side, it seems inconceivable that someone could deny the truths that are so obvious to them. For me, an uptick in total deaths closely matching reports of COVID deaths is pretty convincing, and it is hard for me to make out why anyone in power would want to wreck the economy and could somehow convince countries around the world to overlook a competitive advantage and follow suit. It boggles the mind. Likewise, I can see how climate change threatens powerful interests like the fossil fuel industry and even perhaps capitalism writ large—via the imposition of unwelcome limits on what we can do. But I have a much harder time understanding the bizarre allegations of scientists rolling in dough by hopping on the climate change bandwagon. That’s not how it works, people.

In this post, I will provide an example of how I evaluate the question of whether I have been brainwashed in the case of climate change, contrasting the way my knowledge is “received” to that of the opposition.

Precipitating Event

This post was motivated by someone in the financial world noticing my textbook, thinking well of it, and writing a piece that began with an extended quote from Appendix D.6:

So here’s the thing. The first species smart enough to exploit fossil fuels will do so with reckless abandon. Evolution did not skip steps and create a wise being—despite the fact that the sapiens in our species name means wise (self-assigned flattery). A wise being would recognize early on the damage inherent in profligate use of fossil fuels and would have refrained from unfettered exploitation. Not only is climate change a problem, but building an entire civilization dependent on a finite energy resource and also enabling a widespread degradation of natural ecosystems seems like an amateur blunder.The piece got picked up and published at Zero Hedge, where I made the mistake of scanning the comments. I was appalled, and depressed at the sampling of humanity that we hope will act rationally to avoid the worst fate. It gave me an instant appreciation for the high quality, thoughtful comments posted to Do the Math. Granted, I don’t agree with all commenters, and do reject the occasional vacuous or vitriolic entry. But the Zero Hedge comments were dominated by empty posturing. A common refrain followed the formula:

I stopped reading as soon as I saw climate change.and

Who pays these people to keep writing this BS about climate change?The former showed up so often that I took it as a learned reaction to signal one’s virtue as a denier: an expression and re-validation of tribal identity. The latter made me laugh, on the basis that my book is offered for free, and actually required me to pay for some permissions, ISBN numbers, etc. I also am abandoning a well-funded research career in astrophysics to do this more important work on planetary limits. In academia, by the way, how much grant funding I receive does not determine my salary, so the often-assumed personal gain incentive is not as direct as is imagined. In any case, I am walking away from any known or likely prospect of research funding. So there! I’ll bet that in the eyes of those who think I am grievously wrong, this choice just makes me the saddest sack: duped into believing a big lie and doing the exact opposite of profiting from it. Stupid, squared!

Ironically, climate change was not even the main point of the quoted message, as it seldom is for me. Yet it’s a third rail that made some readers’ eyes bug out, hair stand on end, ears vent steam, and brains shut out the possibility of absorbing anything else in the article.

My Programming on Climate Change

So let me unpack how I became brainwashed to believe that climate change is anthropogenic, and is responsible for rising global temperatures.

Climate change for me is not as much a matter of belief as it is personal investigation and scientific understanding. Like many or most scientists, I see myself as a skeptic, not a follower. Presumably my out-of-the-mainstream message that our entire system and set of values are pointing us toward self-inflicted ruin, or the fact that my primary astrophysics endeavor was to test whether General Relativity is really correct (it seems to be so far), should give credence to this assertion. As a social animal, it can be hard to adopt an isolating, minority view within a department focused on very different matters.

Is climate change a belief for me? I suppose everything in my head could be described at some (pointless?) philosophical level as a belief. I believe the earth is round. True, I have personally measured its radius myself in various validating ways. I believe that air is made of molecules, themselves composed of atoms, even though I have never seen an atom in my direct experience. I believe that light is carried by photons (okay, I have seen/measured individual photons in my lab, and sent them on round-trip journeys to the moon). Any time I have had an opportunity to check some “known” piece of physics/chemistry for myself, I have come out satisfied that the textbooks are not lying to me. I haven’t checked everything: I’m just one person. But myriad other scientists are just like me, and have checked the things I haven’t—over and over, around the world, for decades and even centuries. Believe me, if a scientist has an opportunity to effect the rewriting of standard textbook material, they’ll jump on it—such is the glory of changing a paradigm. Nobel prizes tend to go to those who have made such a revolutionary impact on knowledge and understanding. I think what I’m saying is that scientists—almost by definition—are better described as explorers than as sheep.

But let’s get to climate change, and why for me it’s not entirely “received wisdom” but checks out through my own independent explorations.

First, I am convinced that methane (natural gas) molecules are formed by one carbon and four hydrogen atoms. I cannot claim direct evidence, but understand the process by which such things are determined—having performed similar experiments in chemistry labs to elucidate ratios of atoms in compounds (it also makes sense in terms of shared electrons and number of bonds). Likewise, I trust that oil is composed of hydrocarbon chains: a backbone of carbon atoms and two hydrogen atoms for each carbon, plus one more at each end. If you’re not on board with me at this point, I can’t decide whether to admire your hairshirt-level scientific empiricism or to shake my head at a lost cause.

The next step is easy: once understanding the composition of fossil fuels, it is almost literally childs’ play to introduce diatomic oxygen molecules from air and then rearrange the “balls-on-sticks” models of the molecules into new arrangements that leave CO2 and H2O—carbon dioxide and water. Together with the masses of the constituents (I understand several angles of verifying this, from both chemistry and nuclear physics), it is straightforward to understand that the resulting carbon dioxide mass is roughly three times the mass of the hydrocarbon input—much of the mass coming from the oxygen molecules.

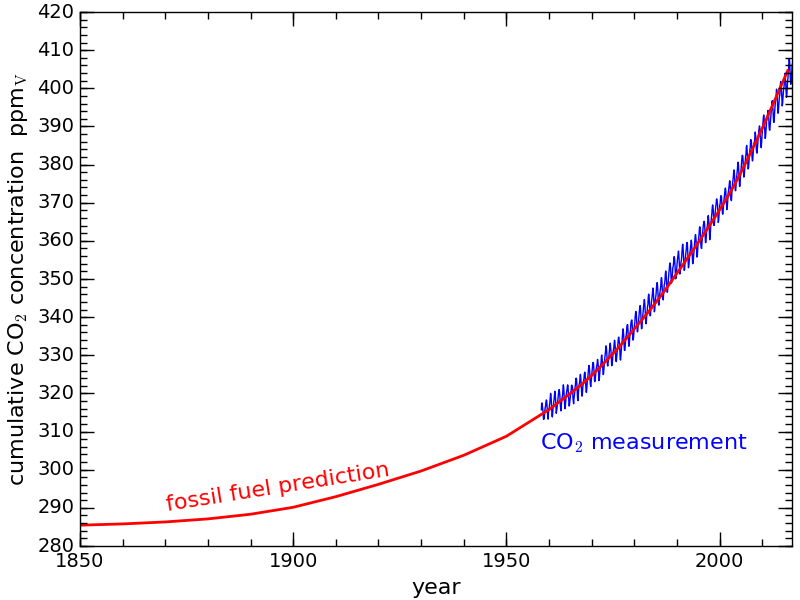

Many years back, I independently checked my understanding—as scientists are prone to do—of the observed CO2 build-up in the atmosphere by estimating how much I would expect it to rise per year based on reported knowledge of global annual fossil fuel consumption, and also the total post-industrial CO2 rise to date based on cumulative fossil fuel use (later conveyed in a Do the Math blog post). The result was actually twice as high as the observed rise, upon which I learned (or “discovered” for myself) that half of the emitted CO2 is absorbed by the ocean/ground. But even leaving this wrinkle aside, it was very powerful to realize that anthropogenic CO2 emission has no problem accounting for enough CO2 to explain the observed rise: we need not look elsewhere for the source.

I took this to a new level in preparing my textbook, deciding to produce a “prediction” graph of CO2 emission over time using as inputs only historical fossil fuel records and knowledge of the chemistry. I overlaid the prediction on the measured CO2 from Mauna Kea (the Keeling curve) to just see how well they agreed. The result, reproduced below, made my jaw drop. I mean, I knew it would be decent, having crudely verified annual increase and cumulative increase before. But seeing the entire shape line up gave me a mic-drop moment. I didn’t do anything to force it to be so good!

Predicted CO2 rise from fossil fuel use (red) atop measured CO2 (blue).

No one gave me this plot. I didn’t find it somewhere. I don’t recall ever having seen one like it. I was curious, and went exploring to see what I would find. I wrote the Python program from scratch that read and parsed the historical fossil fuel data file, performed the chemistry calculations, and generated the graph (see text for details). I feel like I own this result in a way that I never would if somebody just showed it to me. I know what went into it, and why I can trust it.

The final step is an understanding of heat transfer and radiative transport in the atmosphere—both of which I have enough personal context to comfortably assess and understand (believe?). Radiative heat transfer is dear to my heart, and I have made loads of personal measurements/confirmations of how this process works. I have thoroughly explored my world using a thermal-infrared camera, performing supporting calculations; dealt with cryogenics in which radiative heat transfer is an enemy that must be well understood/quantified; validated planetary surface temperatures based on this phenomenon; and obtained countless spectra of stars and galaxies that emit radiative power. No talking head can undo all that personal experience. Also, like all astronomers, my observations have been constrained by atmospheric transmission windows, and I know what happens when I try or hope to get infrared light through the atmosphere at absorbed wavelengths. Those absorption features are real and limit the wavelengths I could observe. It’s not just words in a textbook, for me, but direct experiences at observatories where I have (not) seen the blocked wavelengths with my own tools. Incidentally, my gold-standard reference for describing radiative transport in the atmosphere is by Pierrehumbert in a short article in Physics Today.

Given an understanding of how infrared radiation interacts with atmospheric constituents, I can perform calculations of expected heating from trapped solar input that reasonably match observations and climate science. It all becomes rather transparent and personally accessible.

Epistemology

I should be careful throwing around words I rarely use (physics does not often concern itself with lofty language), but I think this one fits: how we know what we know. I have given an account of my background understanding of climate change. It would be fascinating to get a comparably explicit account from one of the Zero Hedge deniers. I suspect many of them would not operate on that plane, and may not even see the value in such a challenge. But if someone did try to articulate their opposition, what themes would emerge?

Most would present second-hand wisdom: repeating what (select) others had said. Even though I am doing some of that as well (though less selective, concerning chemical composition of octane; historical fossil fuel use; absorption spectrum of the atmosphere), the pieces I rely upon are more foundational and not (really) in dispute. I would call these “facts,” but even that word gets called into question by philosopher-deniers. I might also expect to see plenty of distracting anecdotes, anomalies, and even scientific literature waved around that pokes holes in certain temperature records or the like. In enormous, heterogeneous data sets, some data will inevitably have systematic errors or point to unresolved anomalies at the margins. Sometimes those little wrinkles turn out to be profoundly impactful, but scientists are weighing the totality of evidence, careful not to cherry-pick, always seeking the underlying truth. In the case of climate change denial, the flow seems to be from ideology to evidence/anecdote rather than the other way around. It’s not objective science, at that point.

I don’t have to be cryptic about where one might find a climate change viewpoint opposed to my own: right-wing outlets really thump this stuff. The issue has become politicized, so that a proper citizen of the right-hand tribe should adopt and parrot what they are told from their own trusted sources about climate change. It is easy to imagine the almost inevitable projection: that such a person would assume the left-hand side—teeming with dirty hippies and scientists—is similarly educated/inculcated and just parroting what their side tells them. Brainwashing accusations fly in both directions.

But I hope I have provided a window into the asymmetry of the situation. I stand to gain nothing from climate change being real. In fact, I think we all stand to lose a great deal as a result. Like many scientists, I don’t subscribe to the ideology of climate change because of some handed-down strategy, but because I see its straightforward plausibility flowing out of a solid foundation of directly-experienced physical reality. I don’t give a fig about what Al Gore says just because Al Gore says it. But when so many people—including myself—have independently arrived at the same inconvenient truth based on observation and physical reality, that’s a powerful outcome.

As a result, it is easier for me to accept the veracity of scientific outcomes than it is for me to embrace proclamations from other domains. I know something about the process. While not every scientific publication stands up to the inevitable scrutiny of the scientific community (especially if appearing in the sensational-leaning journal Nature, as we often joke), I have some basis for trusting that experts in the field will pick it apart if they can. Surviving results are strong, indeed. The fact that it’s not a blind trust in science is what makes science trustworthy at all.

On Who’s Authority?

One last comment is that academics who actually use the term “epistemology” on a daily basis often concern themselves with the question of authority. In philosophy, for instance, the body of work has come entirely from the words of people (authorities)—whose names we remember, and whose pictures will be in textbooks (why the picture of a bearded fellow has any relevance, I’ll never know—maybe the beard certifies authority?). When coupled with a political predilection toward authoritarianism, one can see how a statement of some right-wing ideology (e.g., about climate change or COVID) from an authority figure might be taken for truth.

Science, on the other hand, receives its “authority” from nature itself—not from people. The findings are repeatable and testable by experimenters, with or without beards. We would still understand electromagnetism without Maxwell (bearded), or relativity without Einstein (no beard). These bright but happenstance people were in the right place at the right time to be the first to stumble on these emergent truths, but they did not create those truths—much as continents and islands would be just as well known today without Columbus or Magellan having ever been born. The individual is incidental, and authority is irrelevant. This ties to my last post on the primacy of physical constructs over artificial human ones. It’s not all about humans, people!

Brainwashing, Perfected

I must say that part of me admires the clever and effective manipulation that right-wing media outlets have perfected. Rather than studying political science, international relations, and history, politicos on the right often study marketing, psychology, and communications. The recipe that hooks the audience is to hammer the messages:

- The condescending elitists on the other side think you’re dumb.

- We know that you’re smart (wink; we’re experts at lying).

- In fact, we can trust you to understand the following insight that the elitists will label as conspiratorial: you will know it (in your bones) to be true, being as smart as you are.

- Only we can be trusted to tell the truth: don’t bother even looking at the pack of lies in all the the “lamestream” media outlets, even if they are all oddly and independently consistent with each other (see: conspiracy!).