You can't stop a wave... but you can surf. Albert Bates. July 8, 2018.

"Will common sense conservation be enough? Probably not."

Part One

Below is a kite sailboat outracing a 1000 HP speed-boat. Three years ago a lone kiteboarder out-sprinted a 50-meter racing yacht in San Francisco Bay. Team Oracle was in practice sessions for the America’s Cup when they got their clock cleaned.

Whether you come at this from peak oil, financial collapse or climate change, we are about to have a radical shift in global energy.

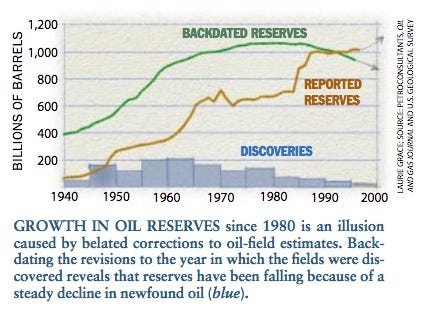

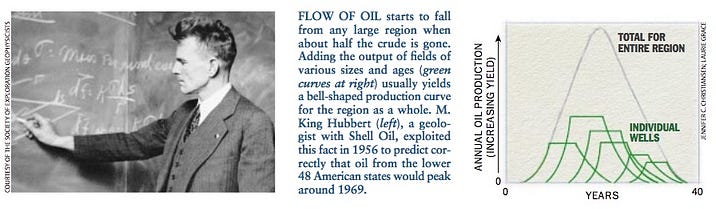

Peak Oil began its tour of the meme-sphere more than 70 years ago when Shell Oil geologist Marion King Hubbert started drawing waves on a chalkboard.

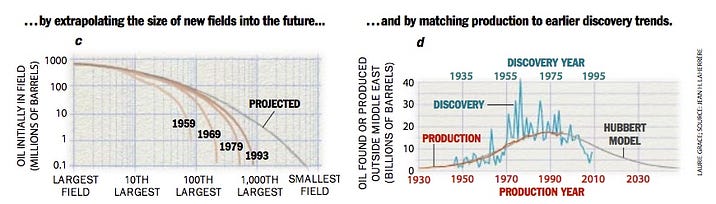

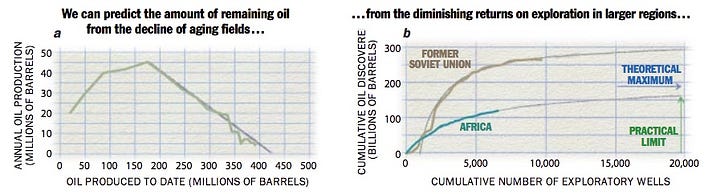

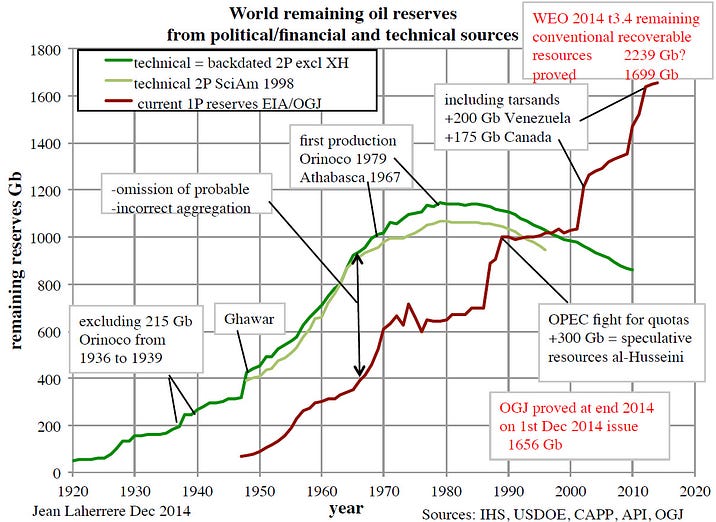

A chart of discoveries and production of crude oil published in Scientific American in 1998 lent renewed urgency to Hubbert’s forecast. Oil geologists were predicting global oil production would plateau soon and start a gradual decline.

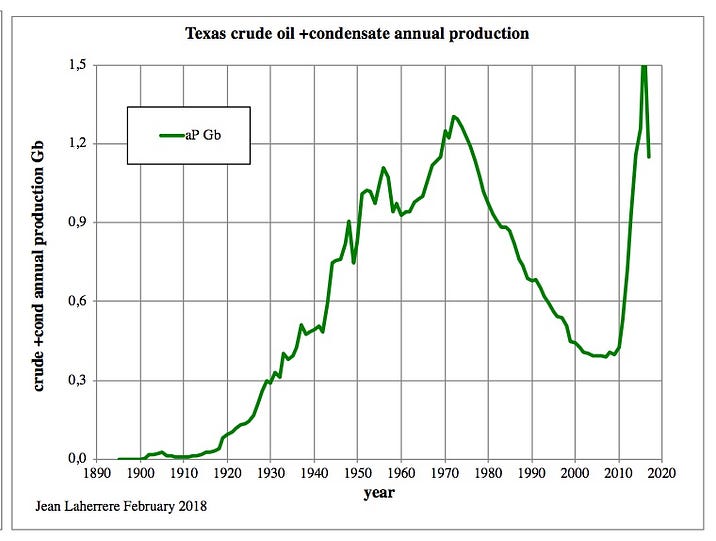

The actual peak for conventional crude came in 2005, but by then the oil companies had a card up their sleeve — hydrofracturing — that opened up previously inaccessible reserves. Just look at what happened to fossil production in the United States, the first to frack.

Hall and Laherrere, 2018

There is just one hitch. Well, actually a couple. Fracking involves cracking rock as far as a mile deep in the Earth, and stimulating gases or fluids trapped there to rise through the fissures and be gathered in wells, then directed to the surface.

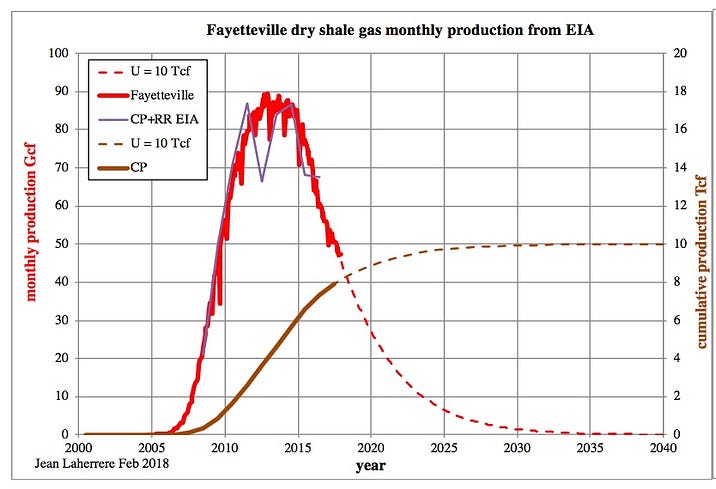

The first hitch is that it is expensive. Even the most profitable companies in the world have been feeling the pinch at present oil prices. The second hitch is that it is only ambulatory care, not a cure. You can see the problem in the upper right corner of the chart above. Fracked formations give up their gas in a burst and then production falls off rapidly. Because of this companies are forced to blast more fractures just to keep pace. The sweet spots are quickly exhausted and what are left are the more expensive, less productive dregs.

Hall and Laherrere, 2018

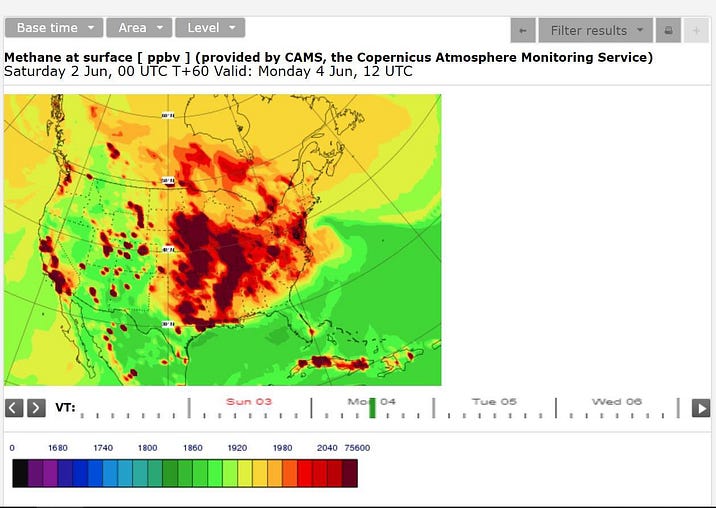

The third hitch is really the most serious, although its been economically externalized by the oil companies. Only some of the fracked gas makes its way to the wells. A lot of it finds fissures not connected to wells and goes straight to the atmosphere. Also, wells leak. All of them. Anywhere from 10 to 30 percent of the reserve goes to the atmosphere through casing cracks, brittle seals, and shifts in the earth, often caused by other nearby drilling.

Methane is 20 to 100 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than Carbon Dioxide

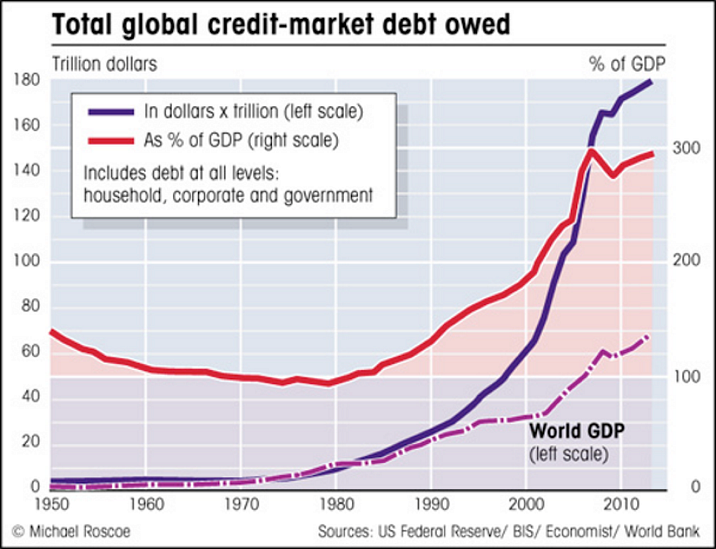

Strapped for cash to keep feeding insatiable consumer demand for petro-utopia, oil companies and governments do what they had always done. They print money. And print. And print. Oh, and sometimes they flip real estate.

That dark cloud you might have noticed on the horizon is the simply gargantuan sovereign debt of $217 trillion. The US leads the pack, with over $20 trillion in debt, but the EU is not far behind with $18 trillion. Japan has racked up $11.5 trillion and Britain has $7.5 trillion. Global debt is more than three times the size of the global economy, the highest it has ever been. The debt is made up of three groups: non-financial corporates, governments and households. The only ones who are doing well are those in the financial sector, and they are now buying private islands and stocking up on canned goods and ammunition.

Then we have Paris. We’ll always have Paris, won’t we? The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change told the 195 assembled heads of state, essentially, their goose is cooked. Smell that fine odor wafting from the kitchen? It is starting to smell a little burnt. It might be time to take it out of the oven.

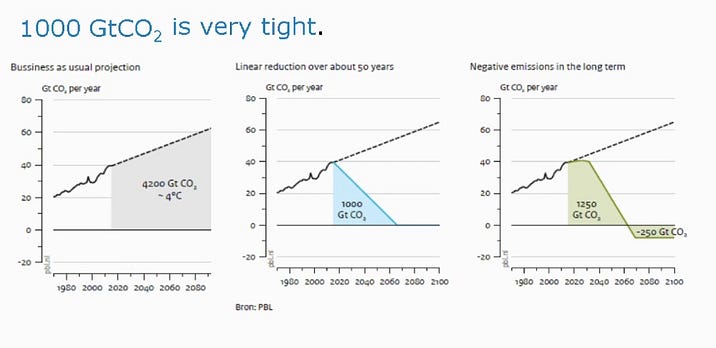

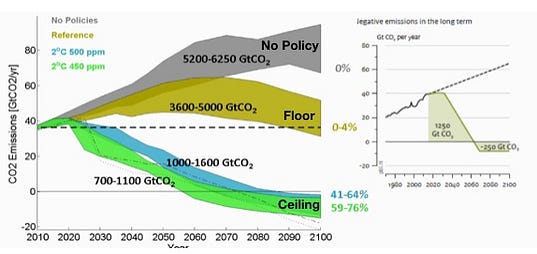

VanVuuren 2018

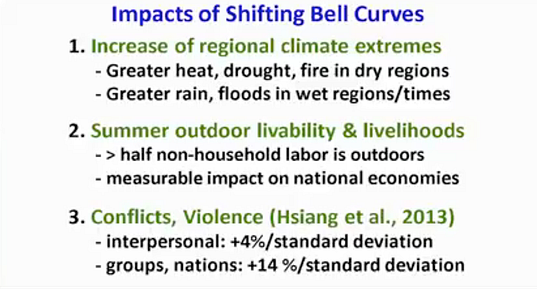

In fact, it is already too late. We will pass the 1.5 degree “aspirational goal” for arresting climate change in a few years, and 2 degrees in another decade or two. We are on a path for nearly 4 degrees by the end of the century, and that assumes everyone meets their pledges to reduce, not a very safe assumption. One of the biggest emitters has already announced it is reneging and is pulling its rusting coal plants out of mothballs. 5 degrees by 2100 is more likely.

Delegates gathered in Marrakech and Bonn to try to find a way back from the cliff and made very slow progress. What is required, beginning about 2020, is a gradually steepening decline in fossil emissions, followed by a half century of negative emissions, or drawdown. There is nothing technologically or economically standing in the way of drawdown now, the impediments are all social and cultural.

Probably the largest impediment is an epidemic addiction to growth. It is still a political mantra most places.

Consider what happens if you propose degrowth. In 1977, Jimmy Carter was briefed on Hubbert’s curve and rushed to tell the public that serious cutbacks would be required. Carter explained that exponential functions have doubling times, and in each successive doubling more is produced than in all the previous doublings combined. Unsustainable on a finite planet, he said.

"The world now uses about 60 million barrels of oil a day and demand increases each year about 5 percent. This means that just to stay even we need the production of a new Texas every year, an Alaskan North Slope every nine months, or a new Saudi Arabia every three years. Obviously, this cannot continue.

***

"The world has not prepared for the future. During the 1950s, people used twice as much oil as during the 1940s. During the 1960s, we used twice as much as during the 1950s. And in each of those decades, more oil was consumed than in all of mankind’s previous history.

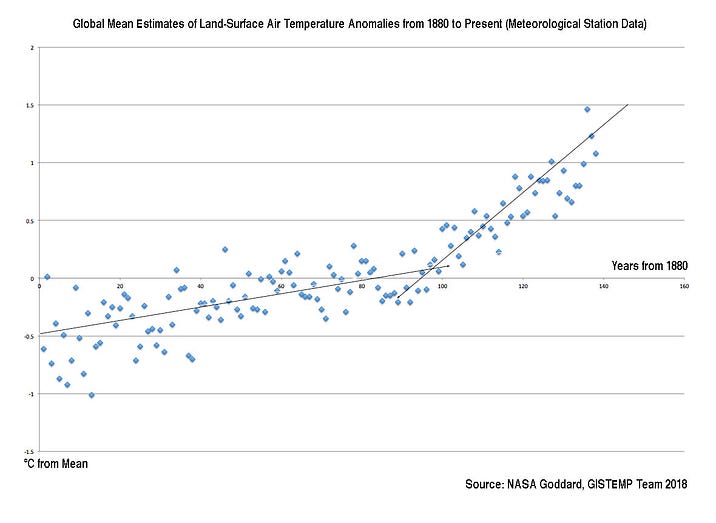

Hansen 2018

"World consumption of oil is still going up. If it were possible to keep it rising during the 1970s and 1980s by 5 percent a year as it has in the past, we could use up all the proven reserves of oil in the entire world by the end of the next decade"

Carter then laid out ten principles, among them “we must start now to develop the new, unconventional sources of energy we will rely on in the next century,” the country had to reduce gasoline consumption by ten percent below its current level, and by the end of his first term there should be solar energy powering more than two and one-half million houses.

Carter urged that prices should generally reflect the true replacement costs of energy. “We are only cheating ourselves if we make energy artificially cheap and use more than we can really afford,” he said.

Peter Menzel, Material World, a Global Family Portrait

“We must ask equal sacrifices from every region, every class of people, every interest group. Industry will have to do its part to conserve, just as the consumers will. The energy producers deserve fair treatment, but we will not let the oil companies profiteer.”

Carter called the challenge the country faced “The Moral Equivalent of War.” We all know what happened next. A deep state cabal, working with the country’s enemies, engineered an October surprise that replaced Carter with a bumbling, affable, senile Hollywood actor who resolutely kept the nation out of that war. It was morning in America. Oil man Dick Cheney ran for Congress.

Bill Clinton opined: “You can’t get elected by promising people less.”

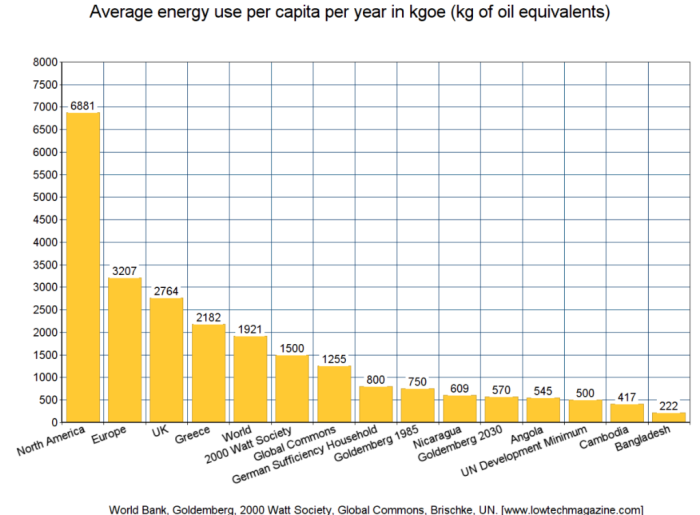

Emissions and energy use are usually framed in terms of national and international percentage reductions, but the energy use per head of the human population varies enormously between and within countries, no matter how it is calculated.

Peter Menzel, Material World, a Global Family Portrait

If we were to divide total primary energy use by regional population, we’d see that the average North American uses more than twice the energy of the average European (6,881 kgoe versus 3,207 kgoe, meaning kg of oil equivalent). Within Europe, the average Norwegian (5,818 kgoe) uses almost three times more energy than the average Greek (2,182 kgoe). The latter uses three to five times more energy than the average Angolan (545 kgoe), Cambodian (417 kgoe) or Nicaraguan (609 kgoe), who uses two to three times the energy of the average Bangladeshi (222 kgoe).

Peter Menzel, Material World, a Global Family Portrait

According to Kris De Decker writing for The DEMAND Centre:

The highest energy users worldwide can contribute 1,000 times as much carbon emissions as the lowest energy users. Inequality not only concerns the quantity of energy, but also its quality. People in industrialized countries have access to a reliable, clean and (seemingly) endless supply of electricity and gas. On the other hand, two in every five people worldwide (3 billion people) rely on wood, charcoal or animal waste to cook their food, and 1.5 billion of them don’t have electric lighting. These fuels cause indoor air pollution [8 million child mortalities per year — more than malaria], and can be time- and labor-intensive to obtain. If modern fuels are available in these countries, they’re often expensive and/or less reliable.

And if provided at that scale, they would wreck the climate even faster, which would seem to be the conflicting agenda of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Decker, Low Tech Magazine 2018.

Decker suggests that:

Focusing on energy services or basic needs can help to specify maximum levels of energy use. Instead of defining minimum energy service levels (such as 300 lumens of light per household), we could define maximum energy services levels (say 2,000 lumens of light per household). These energy service levels could then be combined to calculate maximum energy use levels per capita or household. However, these would be valid only in specific geographical and cultural contexts, such as countries, cities, or neighborhoods — and not universally applicable. Likewise, we could define basic needs and then calculate the energy that is required to meet them in a specific context. For example, central heating and daily hot showers are only a few decades old, but these technologies are now considered to be an essential need by a majority of people in industrialized countries.

Sadly, these days in the industrial world, even the energy poor are living above the carrying capacity of the planet. For example, if the entire UK population were to live according to the minimum energy budget that has been determined in workshops with members of the public, then (consumption-based) emissions per capita would only decrease from 11.8 to 7.3 tonnes per person. The UN Development Program’s Paris-based target is less than 2 long tons C per person per year. The ‘floor’ is 3–6 times higher than the ‘ceiling.’ We need to get to 2 metric tons per capita.

Will common sense conservation be enough? Probably not.

And just how much is 2 tonnes per year?

164 to 227 hamburgers

one fifth of an automobile

1.9 m2 of concrete floor or swimming pool

or

one-eighth of a single BitCoin transaction

You Can't Stop A Wave But You Can Surf-2. Albert Bates. July 15, 2018.

An international team of climate scientists, economists and energy systems modelers have built a range of new “Shared Socioeconomic Pathways” (SSPs) that examine how global society, demographics and economics might change over the next century.

These SSPs are now being used as scenarios for the latest climate models, feeding into the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) due to be published in 2020–21. They are also being used to explore how societal choices will affect greenhouse gas emissions and, therefore, how the social inertia impeding the climate goals of the Paris Agreement could be overcome.

The SSPs are based on five narratives describing broad socioeconomic trends that could shape future society. These include one green economy approach and four variants of business as usual.

Here is how they predict the energy mix will play out through the remainder of this century. Each chart takes 2010 as the starting point, lining up nicely with that last image we used — of global energy consumption.

SSP1 takes the “Green Road.” Consumption is oriented toward low material growth and lower resource and energy intensity. This would be where everyone begins to live more like that family in the yurt.

SSP2 is business as usual. The world follows a path in which social, economic, and technological trends do not shift markedly from historical patterns.

SSP3 is regional rivalry, where reaction to peak oil causes a reflexive turn towards violent tribalism and hoarding. Population growth is low in industrialized and high in developing countries, which creates migration pressures worldwide. Low international priority for addressing environmental concerns, coupled with rapid climate change, leads to strong environmental degradation in some regions.

SSP4 is exploitation of the poor by the rich. Over time, a gap widens between an internationally-connected society that contributes to knowledge- and capital-intensive sectors of the global economy, and a fragmented collection of lower-income, poorly educated societies that work in a labor intensive, low-tech economy. Investments in both carbon-intensive fuels like coal and unconventional oil, and also in low-carbon energy sources, keep wealth inequality growing.

SSP5 is Burning Man. There is a push for economic and social growth coupled with exploitation of abundant fossil fuel resources opened by new technologies and the adoption of resource and energy intensive lifestyles around the world. Bill Gates and Elon Musk invest in geoengineering.

It is difficult to find earthly biophysical support for these projections. In the green pathway (SSP1), emissions peak between 2040 and 2060 — even in the absence of specific climate policies, declining to around 22 to 48 gigatonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) per year by 2100. This results in 3–3.5°C of warming by 2100.

All 5 pathways end in climate change that should be deemed unacceptable, and some would end higher order civilization. SSP5, the high-growth energy-intensive pathway, shows the most overall emissions of any SSP, ranging from 104 to 126 GtCO2 per year in 2100, resulting in warming of 4.7–5.1°C.

So those are your choices, friends. You can follow the path being laid out by IPCC and the United Nations and it marches you to the Gates of Hell.

You can shortcut that process if you follow the path being laid out by the current administration of the United States or its right wing clones soon to follow in goosestep across Europe.

Or you could follow the path mapped by Jimmy Carter on April 18, 1977 and learn to surf. Ride the wave to the beach. Learn to live on less and do it with style and panache.

One way or the other, living on less is in our common future.

Part 3. July 22, 2018.

Just when things seem most dire, and there is no possible escape, we catch another faint flicker of hope. In my two previous installments I laid out the predicament. By now anyone who has followed this blog for a while (and a tip of the hat to our loyal supporters) knows this mantra by heart:

There is a finite supply of fossil fuels, and even if we could discover more and refine them at a reasonable price, we can’t burn them because the atmosphere is so polluted that climate change will kill us.

The energy embodied in traditional fuels — sunlight, wind, tides, currents, plants, animals and humans — is several orders of magnitude more diffuse and difficult to harness than light sweet crude or bituminous coal. The energy density of fossil fuels has made possible the high-level civilization that allows me to type this into your phone.

Nuclear power, apart from the facts that it poisons future generations (ughhh!), or is a gateway drug to WMD (yark!), is also running out of fuel. Nukes all over the world would be shutting down already had not the FSU honored the Megatons to Megawatts Program (killed by Obama) and hammered warheads into zirconium-clad U-235 plowshares to sell on the nukefuels market. There are a few more years of that stuff still out there, especially if the US and Israel join in, but after that, lights out for our friendly atom.

The climate change long predicted (for at least 150 years by our reckoning) is now upon us with delayed vengeance, as are Malthus’ ill tidings. Overcharged fecundity is paired to outsized footprint inversely to what is required, which is no-one’s fault, just bad design. We are an Edsel that sees a Mustang in the mirror. We need eyewash more than anything else.

There are cures for myopic addictions, but the struggle with any addict is to produce permanent change. As we’ve chanted, if we expect to get out of this without going extinct there is only one biophysically verifiable path. We have to go over the Seneca Cliff of industrial collapse and follow an 11 to 20 percent decline grade in carbon emissions for the next 80 or more years, not just to zero, but well beyond. We have to raft through the cascades into Negative Emissions territory — the land called Drawdown — by 2030 if we can, but mid-century at the latest. Getting there somewhat later is not an option. The party will be over. We would be the final progeny of a 100,000-generation run for one magnificent mammal. Then we’ll be no different than the Dodo.

Recently Alex Smith at Radio Ecoshock rebroadcast one of my favorite Australian podcasts, Beyond Zero, and its interview with Oxford researcher Tina Fawcett, author of the book Suicidal Planet, concerning her concept of personal carbon rations.

Let me start by saying that I don’t like the framing of the word “rations.” It might sell well in a culture of stiff upper lips or shared social burdens, but would never get anyone elected in the USA. If you doubt that, go to Plains, Georgia and ask Jimmy Carter.

Fawcett agrees. She has switched to using “carbon allowances.” I still think that is too weak to get broad social buy-in. “Dividend,” after the style of the Alaska Permanent Fund, would be better, had it not already been devalued by deniers and put in the same dung bucket as carbon tax or cap and trade. My personal favorite would be “award” but perhaps readers have suggestions.

Fawcett explains:

“So you would have an annual amount of carbon credits, whatever they get called, in your account, and when you pay for your petrol or diesel at the petrol station or when you pay your electricity bill you’d have to have carbon credits deducted from your account, as well as the money. If you didn’t have a lot of carbon credits left, you know, if you’d already bought a lot of energy that year or had an overseas flight or two, you’d be able to buy additional carbon credits on the market from people who sell them who didn’t need all of them.

“Its not really a parallel currency but it’s a little like that, in that you have to think about both the money and whether you’ve got any carbon allowances left to spend that year. And if not, are you prepared to pay the price to get more?”

No comments:

Post a Comment