Doom and Bloom? Adapting deeply to likely collapse. Jem Bendell. Jan. 15, 2020.

Original version submitted for the XR handbook This is Not a Drill.

Our climate is changing rapidly, destroying lives and threatening our future.

We must act now to reduce harm and save what we can. In doing so we can rediscover what truly matters. That may seem less of a rallying cry than “this is our last chance to prevent disaster”. But I believe it is more truthful and will be more lasting. It will also invite less disillusionment over time. And help each of us to prepare. After all, when harvests collapse, we won’t be eating our placards. We will be relying on the love we have for each other and the ways we have prepared.

Scientists and activists have been shouting for the past fifteen years about the imminent disaster we are creating. The latest message is “we’ve only got 12 years” to prevent a disastrous 1.5 degrees of warming, but I’m not swayed any more. My reading of the latest data is that

climate change has gone too far, too fast, with too much momentum, so that any talk of prevention is actually a form of denial of what is really happening. It is a difficult conclusion to arrive at. And a difficult one to live with.

We have too little resilience in our agricultural, economic, and political systems to be able to cope. It is time to prepare, both emotionally and practically, for a disaster.I am social scientist, not a climatologist. So who am I to spread panic and fear when the world’s top scientists say we have 12 years? Like many readers,

I had assumed the authority on climate was the IPCC – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, but it turns out they’ve been consistently underestimating the changes. In 2007 they said an ice-free Arctic was a possibility by 2100. That sounds far enough away to calm the nerves. But real-time measurements are documenting such rapid loss of ice that some of the world’s top climate scientists are saying it could be ice free in the next few years.

Sea-level rise is a good indicator of the rate of change, because it is affected by many factors. In 2007 satellite data showed a sea level rise of 3.3 mm per year. Yet that year the IPCC offered 1.94mm a year as the lowest mark of its estimate for sea-level rise. Yes, you’re right: that’s lower than what was already happening. It’s like standing up to your knees in flood water in your living room, listening to the forecaster on the radio saying she is not sure if the river will burst its banks. It turned out that when scientists could not agree on how much the melting polar ice sheets would be adding to sea-level rise, they left out the data altogether. Yeah, that’s so poor, it’s almost funny.

Once I realised that the IPCC couldn’t be taken as climate gospel, I looked more closely at some key issues. The Arctic looms large. It acts as the planet’s refrigerator, by reflecting sunlight back into space and by absorbing energy when the ice melts from solid to liquid. Once the Arctic Ice has gone and the dark ocean starts absorbing sunlight, the additional global warming blows the global 2-degree warming target out the window.

The implications even of small changes are immense for our agriculture, water and ecosystems. Even just one warmer summer in the northern hemisphere in 2018 reduced yields of wheat and staples like potatoes by about a quarter in the UK. Unlike other years, the unusual weather was seen across the northern hemisphere, with declines in rain-fed agriculture reported across Europe. Globally we only have grain reserves for about 4 months, so a few consecutive summers like 2018 and the predicted return of El Nino droughts in Asia could cause food shortages on a global scale.

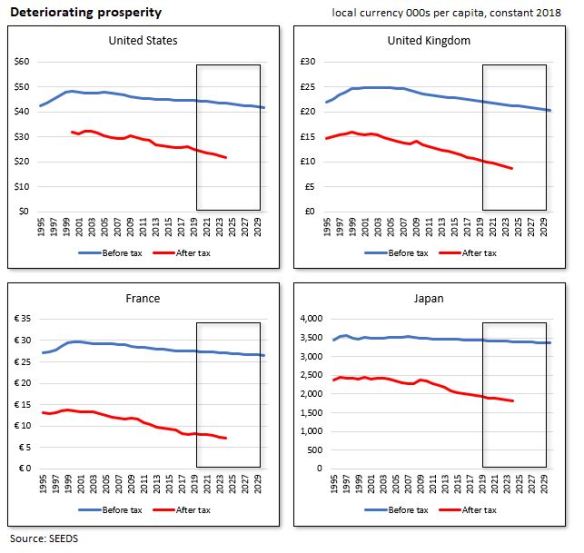

Having gathered a pile of this information I

concluded that our civilisation would struggle to hold itself together under such conditions. I hear many voices fending off despair with hopeful stories about technology, political revolution, or mass spiritual awakenings. But I cannot pin hopes on those things. We should be preparing for a social collapse. By that I mean an uneven ending of our normal modes of sustenance, security, pleasure, identity, meaning, and hope. It is very difficult to predict when a collapse would occur, especially given the complexity of our agricultural and economic systems. Yet everyone with whom I discussed this topic asked me for a prediction. So my guess is that within 10 years from now a social collapse, in some form, will have occurred in the majority of countries around the world.

Having worked for over 25 years in environmental sustainability, I found it hard to accept that my career added up to nothing; my sense of self was shaken because I had believed humanity would ‘win’ in the end. We had been walking up a landslide. I found myself regretting all the times I had settled for small changes when my heart was calling for large ones. I grieved how I may not grow old. I still grieve for those closest to me, and the fear and pain they may feel as their food, energy and social systems break down. Most of all I now grieve for the young, and the more beautiful world they will never inherit.

This realisation meant I began feeling the impermanence of everything in a far more tangible and immediate way than before. My attention had always been fixed in the future, but now arrived in the present, and I became aware as never before of other people and animals – of love, beauty, art, and expression. I was reminded of what my friend with terminal cancer had said about his experience of gratitude and wonder, and of the intense quality of our last meeting.

Over the past year I have met many people for whom an acceptance of the scale and imminence of the crisis has been transformative.

They prioritise truth seeking and telling, inner exploration and self-discovery, self-expression and creativity, connection with others and nature, as well as cultivating their capacity for loving kindness. They are experience a renewed ability to live in what we could call ‘Expressive Presence’.

I am not the first to notice this phenomenon. The mystics have been talking about it for millennia. The Russian author Dostoevsky described the delicious intensity of the last moments before his false execution. I believe we all need to go through such a process, individually and collectively. Putting all our hopes in a better future allows us to make compromises in the present, while letting go of a better future can allow us to drop false hopes and live the present with more integrity. It might even make our activism more effective.

This is a book [This is Not a Drill] about a global rebellion to stop the rapid extinction of species and avert the possible extinction of our own. Being loving and more connected is wonderful but might seem a bit vague and inconsequential. What might we do, as publicly engaged citizens?

If our view is that societal collapse or breakdown is now likely due to climate change, might we communicate that view as widely as possible without offering a set of “answers” and action agendas? When talking with individuals and to small groups, I have witnessed, over and over, that there is a lot that people can gain from feeling lost and despairing before then piecing things back together for themselves, in their personal, professional and political lives. But speaking through the mass media to the general public is a different matter. The limitations of a superficial and combative approach from the news media are well known to those of us who hope for a more informed and engaged public. But on this topic, we have an additional problem. Our dominant culture hides the matter of death and dying away from daily life. The feeling we are part of a society and species that is perpetually improving helps to contain our fear of personal mortality. Without loving support of any kind, a sudden acceptance that collapse is now likely or inevitable in the not-so-distant future could trigger some ugly responses to difficult emotions. A quiet form of hysteria could lead to an outpouring of blame turning inward, and destructive tendencies. Some say this is already happening as people intuit how the story of humanity’s progress has lost its nourishing (or numbing) power.

My view is that normalising discussions about how to prepare for and soften collapse will benefit society. Only collective preparations have a serious chance of working. Deep Adaptation to climate change means asking ourselves and our leaders these four questions.

“How do we keep what we really want to keep?” is the first question to ask, as we seek resilience – the capacity to adapt to changing circumstances, so as to survive with valued norms and behaviours. To illustrate, here are some ideas that can considered for resilience. First, a likely collapse in rain-fed agriculture means governments need to prepare for how to ration some basic foodstuffs as well as supporting the rapid expansion of irrigated production of key crops like potatoes. Second, the way our financial markets will respond to the realisation of climate shocks is unpredictable and the risk is that our systems of both credit and payments could seize up. That means governments need to ensure we have

electronic means of payment outside of the private banking system, so trade can continue if there is a financial collapse. Third, there are responses for resilience that will take a bit longer. For instance, and unfortunately, building desalinisation plants may be key across Southern Europe. Fourth, we should try to buy some more time. Many geoengineering ideas are highly dangerous and impractical. But one makes sense right now. We should be seeding and brightening the clouds above the Arctic immediately, as a global emergency response, similar in scale to how we would react if an Armageddon-sized meteor was hurtling towards Earth.

A second question to ask ourselves is

“what do we need to let go of in order to not make matters worse?” This question helps us explore relinquishment, where people and communities will let go of certain assets, behaviours and beliefs where retaining them could make matters worse. Examples include withdrawing from coastlines, shutting down vulnerable industrial facilities, or giving up expectations for certain types of consumption. There will be the psychological challenge of how to help people who experience dread, grief and confusion. Many of us may be deeply affected by the falling away of our assumption of progress or stability. How do we plan our lives now? That will pose huge communications challenges, if we want to enable compassionate and collaborative responses from each other as much as possible. Helping people with psychological support to let go of some old attachments and aspirations will be important work.

“What can we bring back to help us with the coming difficulties and tragedies?” is the third question I suggest guides our conversations about Deep Adaptation to our climate tragedy. It helps us explore the restoration of attitudes and approaches to life and organisation that our hydrocarbon-fuelled civilisation eroded. Examples include re-wilding landscapes, so they provide more ecological benefits and require less management, changing diets back to match the seasons, rediscovering non-electronically powered forms of play, and increased community-level productivity and support.

The fourth question I invite you to consider is

“what could I make peace with to lessen suffering?” As we contemplate endings our thoughts turn towards reconciliation: with our mistakes, with death, and some would add, with God. We can also seek to be part of reconciliations between peoples with different political persuasions, religions, nations, genders, classes and generations. Without this inner Deep Adaptation to climate collapse we risk tearing societies apart.

Bold emissions cuts and carbon drawdown measures are still necessary to reduce as much as possible the mass extinction and human suffering of climate change, but we must also prepare for what is now inevitable. This Deep Adaptation Agenda takes us beyond mainstream narratives and initiatives on adaptation to climate change, as we no longer assume that society as we know it can continue.

Faced with these scenarios, some people react by calling for whatever-it-takes to be done to stop such a collapse. That is, to attempt whatever draconian measures might cut emissions and drawdown carbon in case it might stop the disaster. The problem is that such a perspective can quickly lead to calls for those with power to impose on people without it. For the powerful to satisfy themselves that they are doing needs to be done no matter what the implication for peoples’ lives and wellbeing. It is now clear that there will be tough decisions ahead. But rather than suggest we can sacrifice our values for a chance to survive, instead we can make universal love our compass as we enter an entirely new physical and psychological terrain.

People often ask me where is the hope in my rather dark analysis of our situation – what vision Deep Adaptation offers to its adherents.

I cannot honestly hope for a better future, so instead I’m hoping for a better present. I’m earning less money and instead I’m eating better and feeling better. I’m not compromising my truth because I have nothing to lose. I’m sleeping more, enjoying more and loving more. In this sense, my life is not doom and gloom. Instead, both doom and bloom are complementary sides to my everyday experience. Climate activism can so easily become angry, dour, moralising, and self-sacrificing, but that must not happen to Extinction Rebellion. With so little future to hope for this rebellion is not worth our misery and pain.

In facing our climate predicament, I have learned that

there is no way to escape despair. But there seems to be a way through despair. It is to love love more than we fear death. That love is why we experience loss and grief. After loss and grief there is still that love. So as things get really difficult in the years to come, I hope I will keep asking myself – what does love invite of me now?