Why action on climate change gets stuck and what to do about it. Matthew Hoffmann (Professor of Political Science and Co-Director Environmental Governance Lab, University of Toronto) & Steven Bernstein (Professor of Political Science and Co-Director of the Environmental Governance Lab, University of Toronto). The Conversation. Jan. 16, 2020.

The Science is settled, the Politics not so much. Tim Watkins, The Consciousness of Sheep. Jan. 27, 2020.

Why Tourism Should Die—and Why It Won’t. Chuck Thompson, New Republic. Jan. 24, 2020.

"Sustainable" travel is an oxymoron.

Blue Acceleration: our dash for ocean resources mirrors what we’ve already done to the land. Robert Blasiak, The Conversation. Jan. 24, 2020.

Pie: Net Zero

Work crews descended on 12 commuter parking lots in Toronto in late November 2018, and headed to the electric vehicle (EV) charging stations. Their work came on the heels of an IPCC report that warned of dire environmental, economic and health consequences in the absence of any serious momentum toward decarbonization by 2030.

But the crews were not adding to the two charging stations installed in each parking lot in 2013. They came to remove them.

This erasure of one provincial government’s climate project by its successor was only the tip of the melting iceberg. The steady unravelling of climate policy began when the newly elected Conservative government cancelled the provincial cap and trade system and renewable energy contracts from Ontario’s feed-in-tariff system. It also removed subsidies for electric vehicles (up to $14,000 per vehicle under the previous government).

Despite being sold as cost-cutting, some of the reversals have been expensive. Cancelling 750 renewable-energy projects, for instance, cost $231 million.

It is tempting to view this unwinding through the lens of the polarized politics plaguing many western democracies. That misses the bigger picture.

Our research on more than two dozen climate initiatives around the world — from the community level to the global scale — revealed that the Ontario story is depressingly familiar. There is no lack of climate initiatives — our case studies are only a small cross-section of thousands. Rather, the problem is that these initiatives tend to get started, make some progress and then get stuck or even regress.

Dependence on fossil energy means it is difficult for a new policy or technology in isolation to catalyze breakthrough changes. Part of the story is the pushback they generate, as happened in Ontario, from political and economic interests that mobilize opposition.

But overt resistance is not the only obstacle to change. Changing one thing often runs into the powerful inertia of related policies, technologies, interests and patterns of behaviour.

The Science is settled, the Politics not so much. Tim Watkins, The Consciousness of Sheep. Jan. 27, 2020.

In the decades since the Kyoto Protocol was signed, the proportion of fossil fuels in the global energy mix shrank from 87 percent to 86 percent – and given China’s infamous lack of transparency, even this reduction has to be taken with a pinch of salt. Over the same period, non-renewable renewable energy-harvesting technologies (excepting hydroelectric) have grown from 1 percent to just under 4 percent; despite a Herculean effort to install them. If the aim were merely to replace our current fossil fuel consumption, we would need install 1,500 windfarms each covering 300 square miles every day between now and 2050. Alternatively, we might opt for nuclear power; in which case we would need to install two 1GW nuclear power stations every three days between now and 2050 (it currently takes around a decade to build just one). And, of course, the need is not just to stop adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere – we have to somehow permanently remove it. Planting trees – even trillions of them (which would involve massive additional fossil fuel use) – would barely scratch the surface; and would likely turn out to be just another corporate welfare scam to funnel money to wealthy landowners.

Cutting energy use is the only non-fossil fuelled means of tackling the issue; but nobody in a position of power is talking about that. For good reason; the 2008 crash, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the two oil shocks in the 1970s are the only times in modern history that global carbon emissions have decreased. Even this level of economic and social disruption barely dented the human carbon footprint. To meaningfully lower carbon emissions would require an economic slowdown on a par with the impact of the fourteenth century Black Death in Europe; and even then, the planet would continue to warm because the blanket of greenhouse gases now surrounding us prevent sufficient solar energy from radiating back into space.

Once, however, the rich realise that even retreating to their bunkers in New Zealand will not save them from the calamity that is racing to meet us; an entirely different – and far less “green” – set of proposals is likely to emerge. I don’t doubt that sooner or later the global rich will turn to geoengineering in a last ditch effort to curb global warming while reaching for a plethora of experimental nuclear technologies in a desperate attempt to offset the coming decline in fossil fuel production. Whether it will work is anybody’s guess; but it is worth remembering that all of the problems we face today are the result of solutions that we put in place in the past.

Why Tourism Should Die—and Why It Won’t. Chuck Thompson, New Republic. Jan. 24, 2020.

"Sustainable" travel is an oxymoron.

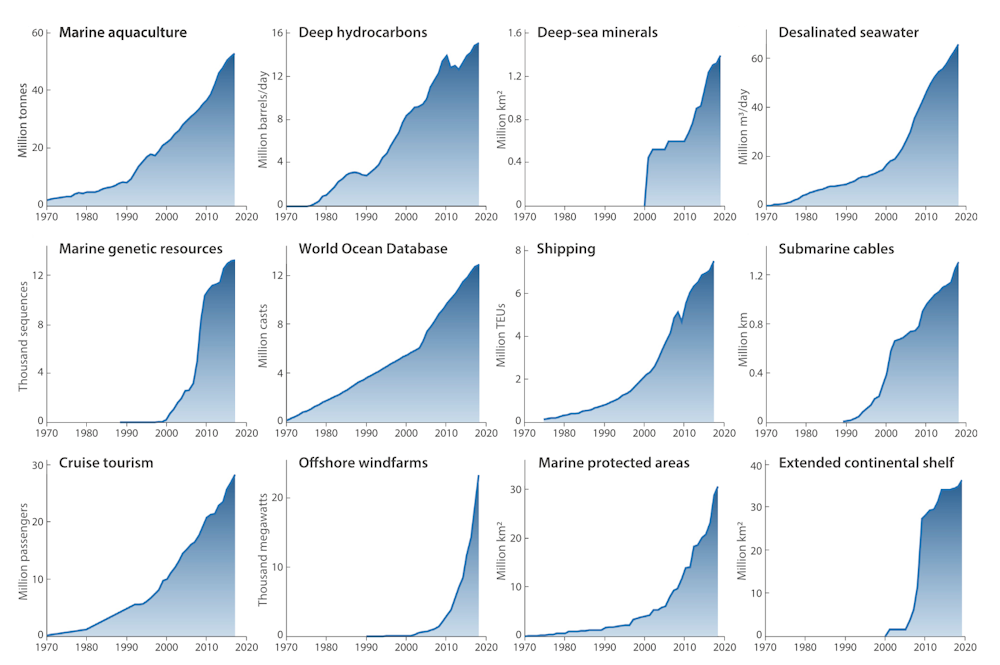

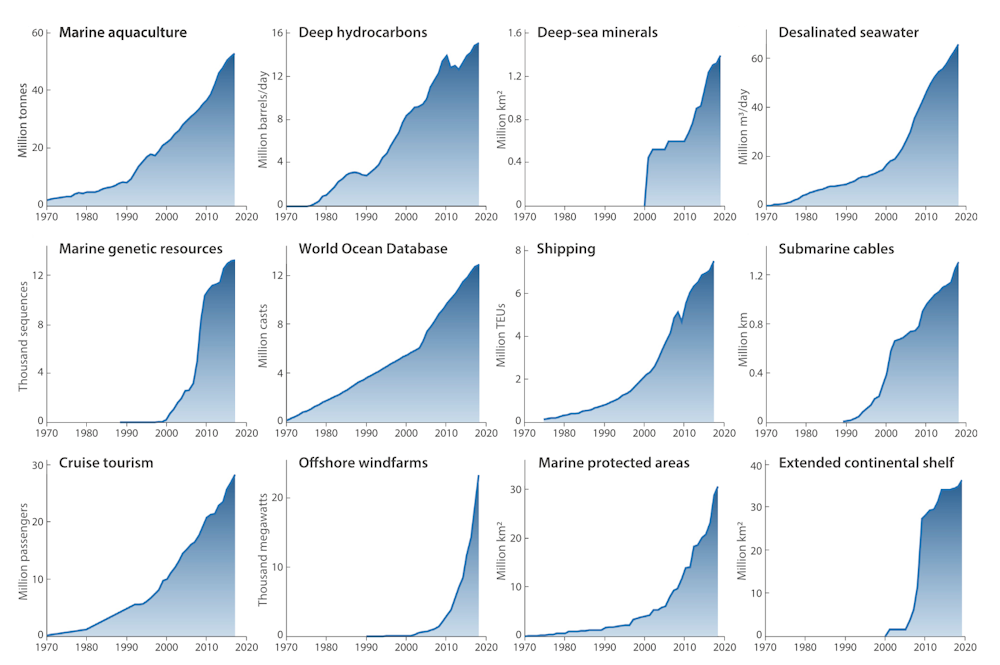

Blue Acceleration: our dash for ocean resources mirrors what we’ve already done to the land. Robert Blasiak, The Conversation. Jan. 24, 2020.

Pie: Net Zero

No comments:

Post a Comment