Sometimes realisation comes in a blinding flash. Blurred outlines snap into shape and suddenly it all makes sense. Underneath such revelations is typically a much slower-dawning process. Doubts at the back of the mind grow. The sense of confusion that things cannot be made to fit together increases until something clicks. Or perhaps snaps.

Collectively we three authors of this article must have spent more than 80 years thinking about climate change. Why has it taken us so long to speak out about the obvious dangers of the concept of net zero? In our defence, the premise of net zero is deceptively simple – and we admit that it deceived us.

The threats of climate change are the direct result of there being too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. So it follows that we must stop emitting more and even remove some of it. This idea is central to the world’s current plan to avoid catastrophe. In fact, there are many suggestions as to how to actually do this, from mass tree planting, to high tech direct air capture devices that suck out carbon dioxide from the air.

Read more: There aren’t enough trees in the world to offset society’s carbon emissions – and there never will be

The current consensus is that if we deploy these and other so-called “carbon dioxide removal” techniques at the same time as reducing our burning of fossil fuels, we can more rapidly halt global warming. Hopefully around the middle of this century we will achieve “net zero”. This is the point at which any residual emissions of greenhouse gases are balanced by technologies removing them from the atmosphere.

This is a great idea, in principle. Unfortunately, in practice it helps perpetuate a belief in technological salvation and diminishes the sense of urgency surrounding the need to curb emissions now.

We have arrived at the painful realisation that the idea of net zero has licensed a recklessly cavalier “burn now, pay later” approach which has seen carbon emissions continue to soar. It has also hastened the destruction of the natural world by increasing deforestation today, and greatly increases the risk of further devastation in the future.

To understand how this has happened, how humanity has gambled its civilisation on no more than promises of future solutions, we must return to the late 1980s, when climate change broke out onto the international stage.

On June 22 1988, James Hansen was the administrator of Nasa’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, a prestigious appointment but someone largely unknown outside of academia.

By the afternoon of the 23rd he was well on the way to becoming the world’s most famous climate scientist. This was as a direct result of his testimony to the US congress, when he forensically presented the evidence that the Earth’s climate was warming and that humans were the primary cause: “The greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.”

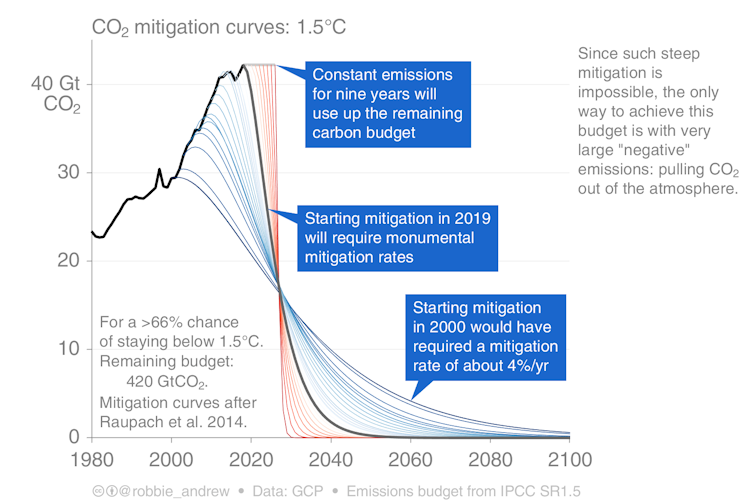

If we had acted on Hanson’s testimony at the time, we would have been able to decarbonise our societies at a rate of around 2% a year in order to give us about a two-in-three chance of limiting warming to no more than 1.5°C. It would have been a huge challenge, but the main task at that time would have been to simply stop the accelerating use of fossil fuels while fairly sharing out future emissions.

Graph demonstrating how fast mitigation has to happen to keep to 1.5℃. © Robbie Andrew,

Four years later, there were glimmers of hope that this would be possible. During the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, all nations agreed to stabilise concentrations of greenhouse gases to ensure that they did not produce dangerous interference with the climate. The 1997 Kyoto Summit attempted to start to put that goal into practice. But as the years passed, the initial task of keeping us safe became increasingly harder given the continual increase in fossil fuel use.

It was around that time that the first computer models linking greenhouse gas emissions to impacts on different sectors of the economy were developed. These hybrid climate-economic models are known as Integrated Assessment Models. They allowed modellers to link economic activity to the climate by, for example, exploring how changes in investments and technology could lead to changes in greenhouse gas emissions.

They seemed like a miracle: you could try out policies on a computer screen before implementing them, saving humanity costly experimentation. They rapidly emerged to become key guidance for climate policy. A primacy they maintain to this day.

Unfortunately, they also removed the need for deep critical thinking. Such models represent society as a web of idealised, emotionless buyers and sellers and thus ignore complex social and political realities, or even the impacts of climate change itself. Their implicit promise is that market-based approaches will always work. This meant that discussions about policies were limited to those most convenient to politicians: incremental changes to legislation and taxes.

Around the time they were first developed, efforts were being made to secure US action on the climate by allowing it to count carbon sinks of the country’s forests. The US argued that if it managed its forests well, it would be able to store a large amount of carbon in trees and soil which should be subtracted from its obligations to limit the burning of coal, oil and gas. In the end, the US largely got its way. Ironically, the concessions were all in vain, since the US senate never ratified the agreement.

Postulating a future with more trees could in effect offset the burning of coal, oil and gas now. As models could easily churn out numbers that saw atmospheric carbon dioxide go as low as one wanted, ever more sophisticated scenarios could be explored which reduced the perceived urgency to reduce fossil fuel use. By including carbon sinks in climate-economic models, a Pandora’s box had been opened.

It’s here we find the genesis of today’s net zero policies.

That said, most attention in the mid-1990s was focused on increasing energy efficiency and energy switching (such as the UK’s move from coal to gas) and the potential of nuclear energy to deliver large amounts of carbon-free electricity. The hope was that such innovations would quickly reverse increases in fossil fuel emissions.

But by around the turn of the new millennium it was clear that such hopes were unfounded. Given their core assumption of incremental change, it was becoming more and more difficult for economic-climate models to find viable pathways to avoid dangerous climate change. In response, the models began to include more and more examples of carbon capture and storage, a technology that could remove the carbon dioxide from coal-fired power stations and then store the captured carbon deep underground indefinitely.

This had been shown to be possible in principle: compressed carbon dioxide had been separated from fossil gas and then injected underground in a number of projects since the 1970s. These Enhanced Oil Recovery schemes were designed to force gases into oil wells in order to push oil towards drilling rigs and so allow more to be recovered – oil that would later be burnt, releasing even more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Carbon capture and storage offered the twist that instead of using the carbon dioxide to extract more oil, the gas would instead be left underground and removed from the atmosphere. This promised breakthrough technology would allow climate friendly coal and so the continued use of this fossil fuel. But long before the world would witness any such schemes, the hypothetical process had been included in climate-economic models. In the end, the mere prospect of carbon capture and storage gave policy makers a way out of making the much needed cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

The rise of net zero

When the international climate change community convened in Copenhagen in 2009 it was clear that carbon capture and storage was not going to be sufficient for two reasons.

First, it still did not exist. There were no carbon capture and storage facilities in operation on any coal fired power station and no prospect the technology was going to have any impact on rising emissions from increased coal use in the foreseeable future.

The biggest barrier to implementation was essentially cost. The motivation to burn vast amounts of coal is to generate relatively cheap electricity. Retrofitting carbon scrubbers on existing power stations, building the infrastructure to pipe captured carbon, and developing suitable geological storage sites required huge sums of money. Consequently the only application of carbon capture in actual operation then – and now – is to use the trapped gas in enhanced oil recovery schemes. Beyond a single demonstrator, there has never been any capture of carbon dioxide from a coal fired power station chimney with that captured carbon then being stored underground.

Just as important, by 2009 it was becoming increasingly clear that it would not be possible to make even the gradual reductions that policy makers demanded. That was the case even if carbon capture and storage was up and running. The amount of carbon dioxide that was being pumped into the air each year meant humanity was rapidly running out of time.

With hopes for a solution to the climate crisis fading again, another magic bullet was required. A technology was needed not only to slow down the increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but actually reverse it. In response, the climate-economic modelling community – already able to include plant-based carbon sinks and geological carbon storage in their models – increasingly adopted the “solution” of combining the two.

So it was that Bioenergy Carbon Capture and Storage, or BECCS, rapidly emerged as the new saviour technology. By burning “replaceable” biomass such as wood, crops, and agricultural waste instead of coal in power stations, and then capturing the carbon dioxide from the power station chimney and storing it underground, BECCS could produce electricity at the same time as removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. That’s because as biomass such as trees grow, they suck in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. By planting trees and other bioenergy crops and storing carbon dioxide released when they are burnt, more carbon could be removed from the atmosphere.

With this new solution in hand the international community regrouped from repeated failures to mount another attempt at reining in our dangerous interference with the climate. The scene was set for the crucial 2015 climate conference in Paris.

A Parisian false dawn

As its general secretary brought the 21st United Nations conference on climate change to an end, a great roar issued from the crowd. People leaped to their feet, strangers embraced, tears welled up in eyes bloodshot from lack of sleep.

The emotions on display on December 13, 2015 were not just for the cameras. After weeks of gruelling high-level negotiations in Paris a breakthrough had finally been achieved. Against all expectations, after decades of false starts and failures, the international community had finally agreed to do what it took to limit global warming to well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement was a stunning victory for those most at risk from climate change. Rich industrialised nations will be increasingly impacted as global temperatures rise. But it’s the low lying island states such as the Maldives and the Marshall Islands that are at imminent existential risk. As a later UN special report made clear, if the Paris Agreement was unable to limit global warming to 1.5°C, the number of lives lost to more intense storms, fires, heatwaves, famines and floods would significantly increase.

But dig a little deeper and you could find another emotion lurking within delegates on December 13. Doubt. We struggle to name any climate scientist who at that time thought the Paris Agreement was feasible. We have since been told by some scientists that the Paris Agreement was “of course important for climate justice but unworkable” and “a complete shock, no one thought limiting to 1.5°C was possible”. Rather than being able to limit warming to 1.5°C, a senior academic involved in the IPCC concluded we were heading beyond 3°C by the end of this century.

Instead of confront our doubts, we scientists decided to construct ever more elaborate fantasy worlds in which we would be safe. The price to pay for our cowardice: having to keep our mouths shut about the ever growing absurdity of the required planetary-scale carbon dioxide removal.

Taking centre stage was BECCS because at the time this was the only way climate-economic models could find scenarios that would be consistent with the Paris Agreement. Rather than stabilise, global emissions of carbon dioxide had increased some 60% since 1992.

Alas, BECCS, just like all the previous solutions, was too good to be true.

Across the scenarios produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) with a 66% or better chance of limiting temperature increase to 1.5°C, BECCS would need to remove 12 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year. BECCS at this scale would require massive planting schemes for trees and bioenergy crops.

The Earth certainly needs more trees. Humanity has cut down some three trillion since we first started farming some 13,000 years ago. But rather than allow ecosystems to recover from human impacts and forests to regrow, BECCS generally refers to dedicated industrial-scale plantations regularly harvested for bioenergy rather than carbon stored away in forest trunks, roots and soils.

Currently, the two most efficient biofuels are sugarcane for bioethanol and palm oil for biodiesel – both grown in the tropics. Endless rows of such fast growing monoculture trees or other bioenergy crops harvested at frequent intervals devastate biodiversity.

It has been estimated that BECCS would demand between 0.4 and 1.2 billion hectares of land. That’s 25% to 80% of all the land currently under cultivation. How will that be achieved at the same time as feeding 8-10 billion people around the middle of the century or without destroying native vegetation and biodiversity?

Read more: Carbon capture on power stations burning woodchips is not the green gamechanger many think it is

Growing billions of trees would consume vast amounts of water – in some places where people are already thirsty. Increasing forest cover in higher latitudes can have an overall warming effect because replacing grassland or fields with forests means the land surface becomes darker. This darker land absorbs more energy from the Sun and so temperatures rise. Focusing on developing vast plantations in poorer tropical nations comes with real risks of people being driven off their lands.

And it is often forgotten that trees and the land in general already soak up and store away vast amounts of carbon through what is called the natural terrestrial carbon sink. Interfering with it could both disrupt the sink and lead to double accounting.

Pipe dreams

Given the dawning realisation of how difficult Paris would be in the light of ever rising emissions and limited potential of BECCS, a new buzzword emerged in policy circles: the “overshoot scenario”. Temperatures would be allowed to go beyond 1.5°C in the near term, but then be brought down with a range of carbon dioxide removal by the end of the century. This means that net zero actually means carbon negative. Within a few decades, we will need to transform our civilisation from one that currently pumps out 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year, to one that produces a net removal of tens of billions.

Mass tree planting, for bioenergy or as an attempt at offsetting, had been the latest attempt to stall cuts in fossil fuel use. But the ever-increasing need for carbon removal was calling for more. This is why the idea of direct air capture, now being touted by some as the most promising technology out there, has taken hold. It is generally more benign to ecosystems because it requires significantly less land to operate than BECCS, including the land needed to power them using wind or solar panels.

Unfortunately, it is widely believed that direct air capture, because of its exorbitant costs and energy demand, if it ever becomes feasible to be deployed at scale, will not be able to compete with BECCS with its voracious appetite for prime agricultural land.

It should now be getting clear where the journey is heading. As the mirage of each magical technical solution disappears, another equally unworkable alternative pops up to take its place. The next is already on the horizon – and it’s even more ghastly. Once we realise net zero will not happen in time or even at all, geoengineering – the deliberate and large scale intervention in the Earth’s climate system – will probably be invoked as the solution to limit temperature increases.

One of the most researched geoengineering ideas is solar radiation management – the injection of millions of tons of sulphuric acid into the stratosphere that will reflect some of the Sun’s energy away from the Earth. It is a wild idea, but some academics and politicians are deadly serious, despite significant risks. The US National Academies of Sciences, for example, has recommended allocating up to US$200 million over the next five years to explore how geoengineering could be deployed and regulated. Funding and research in this area is sure to significantly increase.

In principle there is nothing wrong or dangerous about carbon dioxide removal proposals. In fact developing ways of reducing concentrations of carbon dioxide can feel tremendously exciting. You are using science and engineering to save humanity from disaster. What you are doing is important. There is also the realisation that carbon removal will be needed to mop up some of the emissions from sectors such as aviation and cement production. So there will be some small role for a number of different carbon dioxide removal approaches.

The problems come when it is assumed that these can be deployed at vast scale. This effectively serves as a blank cheque for the continued burning of fossil fuels and the acceleration of habitat destruction.

Carbon reduction technologies and geoengineering should be seen as a sort of ejector seat that could propel humanity away from rapid and catastrophic environmental change. Just like an ejector seat in a jet aircraft, it should only be used as the very last resort. However, policymakers and businesses appear to be entirely serious about deploying highly speculative technologies as a way to land our civilisation at a sustainable destination. In fact, these are no more than fairy tales.

The only way to keep humanity safe is the immediate and sustained radical cuts to greenhouse gas emissions in a socially just way.

Academics typically see themselves as servants to society. Indeed, many are employed as civil servants. Those working at the climate science and policy interface desperately wrestle with an increasingly difficult problem. Similarly, those that champion net zero as a way of breaking through barriers holding back effective action on the climate also work with the very best of intentions.

The tragedy is that their collective efforts were never able to mount an effective challenge to a climate policy process that would only allow a narrow range of scenarios to be explored.

Most academics feel distinctly uncomfortable stepping over the invisible line that separates their day job from wider social and political concerns. There are genuine fears that being seen as advocates for or against particular issues could threaten their perceived independence. Scientists are one of the most trusted professions. Trust is very hard to build and easy to destroy.

But there is another invisible line, the one that separates maintaining academic integrity and self-censorship. As scientists, we are taught to be sceptical, to subject hypotheses to rigorous tests and interrogation. But when it comes to perhaps the greatest challenge humanity faces, we often show a dangerous lack of critical analysis.

In private, scientists express significant scepticism about the Paris Agreement, BECCS, offsetting, geoengineering and net zero. Apart from some notable exceptions, in public we quietly go about our work, apply for funding, publish papers and teach. The path to disastrous climate change is paved with feasibility studies and impact assessments.

Rather than acknowledge the seriousness of our situation, we instead continue to participate in the fantasy of net zero. What will we do when reality bites? What will we say to our friends and loved ones about our failure to speak out now?

The time has come to voice our fears and be honest with wider society. Current net zero policies will not keep warming to within 1.5°C because they were never intended to. They were and still are driven by a need to protect business as usual, not the climate. If we want to keep people safe then large and sustained cuts to carbon emissions need to happen now. That is the very simple acid test that must be applied to all climate policies. The time for wishful thinking is over.