The Collapse of Civilization May Have Already Begun. Nafeez Ahmed, vice. com. November 22, 2019.

Scientists disagree on the timeline of collapse and whether it's imminent. But can we afford to be wrong? And what comes after?

“It is now too late to stop a future collapse of our societies because of climate change.”

These are not the words of a tinfoil hat-donning survivalist. This is from a paper delivered by a senior sustainability academic at a leading business school to the European Commission in Brussels, earlier this year. Before that, he delivered a similar message to a UN conference:

“Climate change is now a planetary emergency posing an existential threat to humanity.”

In the age of climate chaos, the collapse of civilization has moved from being a fringe, taboo issue to a more mainstream concern.

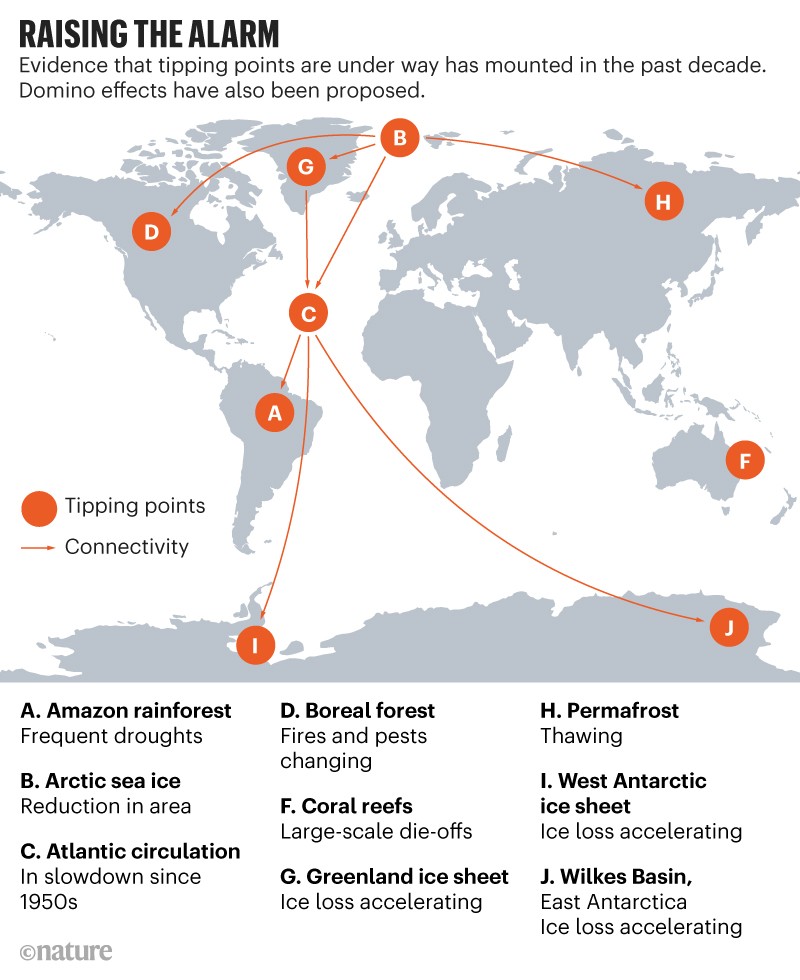

As the world reels under each new outbreak of crisis—record heatwaves across the Western hemisphere, devastating fires across the Amazon rainforest, the slow-moving Hurricane Dorian, severe ice melting at the poles—the question of how bad things might get, and how soon, has become increasingly urgent.

The fear of collapse is evident in the framing of movements such as ‘Extinction Rebellion’ and in resounding warnings that business-as-usual means heading toward an uninhabitable planet.

But a growing number of experts not only point at

the looming possibility that human civilization itself is at risk; some believe that the science shows it is already too late to prevent collapse. The outcome of the debate on this is obviously critical: it throws light on whether and how societies should adjust to this uncertain landscape.

Yet this is not just a scientific debate. It also raises difficult moral questions about what kind of action is warranted to prepare for, or attempt to avoid, the worst. Scientists may disagree about the timeline of collapse, but many argue that this is entirely beside the point. While scientists and politicians quibble over timelines and half measures, or how bad it'll all be, we are losing precious time. With the stakes being total collapse, some scientists are increasingly arguing that

we should fundamentally change the structure of society just to be safe.

Jem Bendell, a former consultant to the United Nations and longtime Professor of Sustainability Leadership at the University of Cumbria’s Department of Business, delivered a paper in May 2019 explaining how people and communities might “adapt to climate-induced disruption.”

Bendell’s thesis is not only that societal collapse due to climate change is on its way, but that it is, in effect, already here. “Climate change will disrupt your way of life in your lifetimes,” he told the audience at a climate change conference organized by the European Commission.

Devastating consequences, like “the cascading effects of widespread and repeated harvest failures” are now unavoidable, Bendell’s paper says.

He argues

this is not so much a doom-and-gloom scenario as a case of waking up to reality, so that we can do as much as we can to save as many lives as possible. His recommended response is what he calls “Deep Adaptation,” which requires going beyond “mere adjustments to our existing economic system and infrastructure, in order

to prepare us for the breakdown or collapse of normal societal functions.”

Bendell’s message has since gained a mass following and high-level attention. It is partly responsible for inspiring the new wave of climate protests reverberating around the world.

In March, he launched the Deep Adaptation Forum to connect and support people who, in the face of “inevitable” societal collapse, want to explore how they can “reduce suffering, while saving more of society and the natural world.” Over the last six months, the Forum has gathered more than 10,000 participants. More than 600,000 people have downloaded Bendell’s paper, called Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating our Climate Tragedy, published by the University of Cumbria’s Institute of Leadership and Sustainability (IFALS). And many of the key organizers behind the Extinction Rebellion (XR) campaign joined the protest movement after reading it.

“There will be a near-term collapse in society with serious ramifications for the lives of readers,” concludes that paper, released in 2017.

Catastrophe is “probable,” it adds, and extinction “is possible.” Over coming decades, we will see the escalating impacts of the fossil fuel pollution we have already pumped into the atmosphere and oceans.

Even if we ceased emissions tomorrow, Bendell argues, the latest climate science shows that “we are now in a climate emergency, which will increasingly disrupt our way of life… a societal collapse is now inevitable within the lifetimes of readers of this paper.”

Bendell puts a rough timeline on this. Collapse will happen within 10 years and inflict disruptions across nations, involving “increased levels of malnutrition, starvation, disease, civil conflict, and war.”

Yet this diagnosis opens up far more questions than it answers. I was left wondering: Which societies are at risk of collapsing due to climate change, and when? Some societies or all societies? Simultaneously or sequentially? Why some rather than others? And how long will the collapse process take? Where will it start, and in what sector? How will that impact others sectors? Or will it take down all sectors of societies in one fell swoop? And what does any of this imply for whether, or how, we might prepare for collapse?

In attempting to answer these questions, I spoke to a wide-range of scientists and experts, and took a deep dive into the obscure but emerging science of how societies and civilizations collapse. I wanted to understand not just whether Bendell’s forecast was right, but to find out what a range experts from climate scientists to risk analysts were unearthing about the possibility of our societies collapsing in coming years and decades.

The emerging science of collapse is still, unfortunately, a nascent field. That's because it's an interdisciplinary science that encompasses not only the incredibly complex, interconnected natural systems that comprise the Earth System, but also has to make sense of how those systems interact with the complex, interconnected social, political, economic, and cultural systems of the Human System.

What I discovered provoked a wide range of emotions. I was at times surprised and shocked, often frightened, sometimes relieved. Mostly, I was unsettled. Many scientists exposed flaws in Bendell’s argument. Most rejected the idea of inevitable near-term collapse outright. But to figure out whether a near-term collapse scenario of some kind was likely led me far beyond Bendell. A number of world leading experts told me that

such a scenario might, in fact, be far more plausible than conventionally presumed.

Science, gut, or a bit of both?

According to Penn State professor

Michael Mann, one of the world’s most renowned climate scientists, Bendell’s grasp of the climate science is deeply flawed.

“To me, this paper is a perfect storm of misguidedness and wrongheadedness,” he told me.

Bendell’s original paper had been rejected for publication by the peer-reviewed Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. According to Bendell, the changes that editorial reviewers said were necessary to make the article fit for publication made no sense. But among them, one referee questioned whether Bendell’s presentation of climate data actually supported his conclusion: “I am not sure that the extensive presentation of climate data supports the core argument of the paper in a meaningful way.”

In his response, sent in the form of a letter to the journal’s chief editor, Bendell wrote: “Yet the summary of science is the core of the paper as everything then flows from the conclusion of that analysis. Note that the science I summarise is about what is happening right now, rather than models or theories of complex adaptive systems which the reviewer would have preferred.”

But in Mann’s view, the paper’s failure to pass peer review was not simply because it didn’t fit outmoded academic etiquette, but for the far more serious reason that it lacks scientific rigor. Bendell, he said, is simply “wrong on the science and impacts: There is no credible evidence that we face ‘inevitable near-term collapse.’”

Dr. Gavin Schmidt, head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, who is also world-famous, was even more scathing.

“There are both valid points and unjustified statements throughout,” he told me about Bendell's paper. “Model projections have not underestimated temperature changes, not everything that is non-linear is therefore ‘out of control.’ Blaming ‘increased volatility from more energy in the atmosphere’ for anything is silly. The evidence for ‘inevitable societal collapse’ is very weak to non-existent.”

Schmidt did not rule out that we are likely to see more instances of local collapse events. “Obviously we have seen such collapses in specific locations associated with extreme storm impacts,” he said. He listed off a number of examples—Puerto Rico, Barbuda, Haiti, and New Orleans—explaining that while local collapses in certain regions could be possible, it's a "much harder case to make" at a global level. "And this paper doesn't make it. I’m not particularly sanguine about what is going to happen, but this is not based on anything real.”

Jeremy Lent, systems theorist and author of The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, argues that throughout Bendell’s paper he frequently slips between the terms “inevitable,” “probably,” and “likely.”

“If he chooses to go with his gut instinct and conclude collapse is inevitable, he has every right to do so,” Lent said, “but I believe it’s irresponsible to package this as a scientifically valid conclusion, and thereby criticize those who interpret the data otherwise as being in denial.”

When I pressed Bendell on this issue, he pushed back against the idea that he was putting forward a hard, scientifically-valid forecast, describing it as a “guess”: “I say in the original paper that I am only guessing at when social collapse will occur. I have said or written that every time I mention that time horizon.”

But why offer this guess at all? “The problem I have with the argument that I should not give a time horizon like 10 years is that

not deciding on a time horizon acts as a psychological escape from facing our predicament. If we can push this problem out into 2040 or 2050, it somehow feels less pressing. Yet, look around. Already harvests are failing because of weather made worse by climate change.”

Bendell points out that such impacts are already damaging more vulnerable, poorer societies than our own. He says it is only a matter of time before they damage the normal functioning of “most countries in the world.”

Global food system failure

According to Dr. Wolfgang Knorr, Principal Investigator at Lund University’s Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in a Changing Climate Program,

the risk of near-term collapse should be taken far more seriously by climate scientists, given the fact that so much is unknown about climate tipping points: “I am not saying that Bendell is right or wrong. But the criticism of Bendell’s points focuses too much on the detail and in that way studiously tries to avoid the bigger picture. The available data points to the fact that some

catastrophic climate change is inevitable."

Bendell argues that the main trigger for some sort of collapse—which he defines as “an uneven ending of our normal modes of sustenance, security, pleasure, identity, meaning, and hope”—will come from

accelerating failures in the global food system.

We know that it is a distinct possibility that so-called multi-breadbasket failures (when major yield reductions take place simultaneously across agricultural areas producing staple crops like rice, wheat, or maize) can be triggered by climate change—and have already happened.

As shown by American physicist Dr. Yaneer Ban Yam and his team at the New England Complex Systems Institute, in the years preceding 2011, global food price spikes linked to climate breakdown played a role in triggering the ‘Arab Spring’ uprisings. And according to hydroclimatologist Dr. Peter Gleick, climate-induced drought amplified the impact of socio-political and economic mismanagement, inflicting agricultural failures in Syria. These drove mass migrations within the country, in turn laying the groundwork for sectarian tensions that spilled over into a protracted conflict.

In my own work, I found that the Syrian conflict was not just triggered by climate change, but a range of intersecting factors—Syria’s domestic crude oil production had peaked in the mid-90s, leading state revenues to hemorrhage as oil production and exports declined. When global climate chaos triggered food price spikes, the state had begun slashing domestic fuel and food subsidies, already reeling from the impact of economic mismanagement and corruption resulting in massive debt levels. And so, a large young population overwhelmed with unemployment and emboldened by decades of political repression took to the streets when they could not afford basic bread. Syria has since collapsed into ceaseless civil war.

This is a case of what Professor

Thomas-Homer Dixon, University Research Chair in the University of Waterloo’s Faculty of Environment, describes as “

synchronous failure”—when

multiple, interconnected stressors amplify over time before triggering self-reinforcing feedback loops which result in them all failing at the same time. In his book, The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity and the Renewal of Civilization, he explains how the resulting convergence of crises overwhelms disparate political, economic and administrative functions, which are not designed for such complex events.

From this lens, climate-induced collapse has already happened, though it is exacerbated by and amplifies the failure of myriad human systems. Is Syria a case-study of what is in store for the world? And is it inevitable within the next decade?

In a major report released in August, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that hunger has already been rising worldwide due to climate impacts. A senior NASA scientist, Cynthia Rosenzweig, was a lead author of the study, which warned that the continued rise in carbon emissions would drive a rise in global average temperatures of 2°C in turn

triggering a “very high” risk to food supplies toward mid-century. Food shortages would hit vulnerable, poorer regions, but affluent nations may also be in the firing line. As a new study from the UK Parliamentary Environment Audit Committee concludes, fruit and vegetable imports to countries like Britain might be cut short if a crisis breaks out.

When exactly such a crisis might happen is not clear. Neither reports suggest it would result in the collapse of civilization, or even most countries, within 10 years. And the UN also emphasizes that it is not too late to avert these risks through a shift to organic and agro-ecological methods.

NASA’s Gavin Schmidt acknowledged “increasing impacts from climate change on global food production,” but said that a collapse “is not predicted and certainly not inevitable.”

The catastrophic ‘do-nothing’ scenario

A few years ago, though, I discovered first-hand that a catastrophic collapse of the global food system is possible in coming decades if we don’t change course. At the time I was a visiting research fellow at Anglia Ruskin University’s Global Sustainability Institute, and I had been invited to a steering committee meeting for the Institute’s Global Research Observatory (GRO), a research program developing new models of global crisis.

One particular model, the Dawe Global Security Model, was focused on the risk of another global food crisis, similar to what triggered the Arab Spring.

“We ran the model forward to the year 2040, along a business-as-usual trajectory based on ‘do-nothing’ trends—that is, without any feedback loops that would change the underlying trend,” said institute director Aled Jones to the group of stakeholders in the room, which included UK government officials. “The results show that

based on plausible climate trends, and a total failure to change course, the global food supply system would face catastrophic losses, and an unprecedented epidemic of food riots. In this scenario, global society essentially collapses as food production falls permanently short of consumption.”

Jones was at pains to clarify that this model-run could not be taken as a forecast, particularly as mitigation policies are already emerging in response to concern about such an outcome: “This scenario is based on simply running the model forward,” he said. “The model is a short-term model. It’s not designed to run this long, as in the real world trends are always likely to change, whether for better or worse.”

Someone asked, “Okay, but what you’re saying is that

if there is no change in current trends, then this is the outcome?”

“Yes,” Jones replied quietly.

The Dawe Global Security Model put this potential crisis two decades from now. Is it implausible that the scenario might happen much earlier? And if so why aren’t we preparing for this risk?

When I asked UN disaster risk advisor Scott Williams about a near-term global food crisis scenario, he pointed out that this year’s UN flagship global disaster risk assessment was very much aware of the

danger of another global "multiple breadbasket failure."

“A projected increase in extreme climate events and an increasingly interdependent food supply system pose a threat to global food security,” warned the UN Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction released in May. “For instance, local shocks can have far-reaching effects on global agricultural markets.”

Climate models we've been using are not too alarmist; they are consistently too conservative, and we have only recently understood how bad the situation really is.

Current agricultural modelling, the UN report said, does not sufficiently account for these complex interconnections. The report warns that “climate shocks and consequent crop failure in one of the global cereal breadbaskets might have knock-on effects on the global agricultural market. The turbulences are exacerbated if more than one of the main crop-producing regions suffers from losses simultaneously.”

Williams, who was a coordinating lead author of the UN global disaster risk assessment, put it more bluntly: “

In a nutshell, Bendell is closer to the mark than his critics.”

He pointed me to the second chapter of the UN report which, he said, expressed the imminent risk to global civilization in a “necessarily politically desensitized” form.

The chapter is “close to stating that ‘collapse is inevitable’ and that the methods that we—scientists, modellers, researchers, etc—are using are wholly inadequate to understand that nature of complex, uncertain ‘transitions,’ in other words, collapses.”

Williams fell short of saying that such a collapse scenario was definitely unavoidable, and the UN report—while setting out an alarming level of risk—did not do so either. What they did make clear is that a major global food crisis could erupt unexpectedly, with climate change as a key trigger.

Climate tipping points

A new study by a team of scientists at Oxford, Bristol, and Austria concludes that our current carbon emissions trajectory hugely increases this risk. Published in October in the journal Agricultural Systems, the study warns that the rise in global average temperatures is increasing the likelihood of “production shocks” affecting an increasingly interconnected global food system.

Surpassing the 1.5 °C threshold could potentially trigger major “production losses” of millions of tonnes of maize, wheat and soybean.

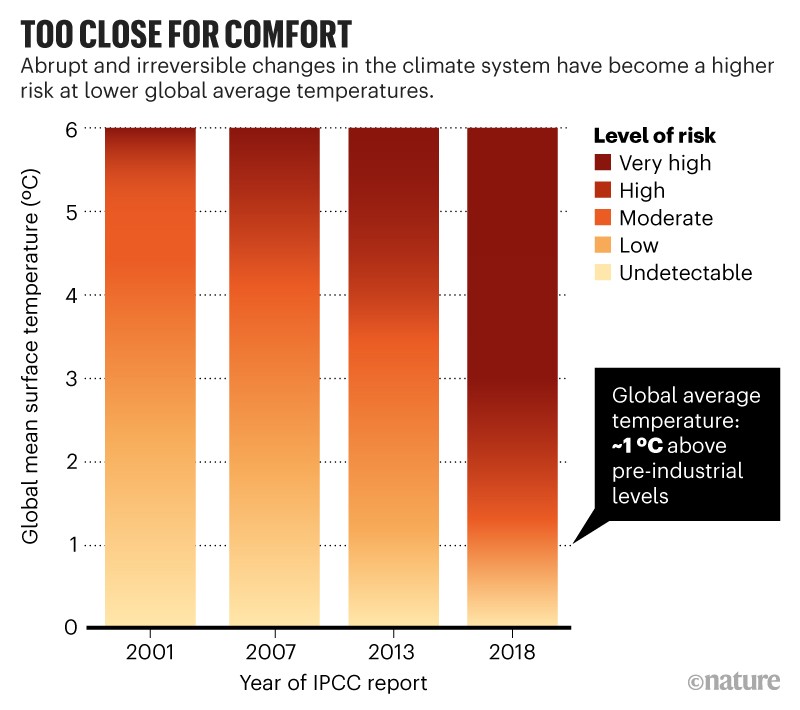

Right now, carbon dioxide emissions are on track to dramatically increase this risk of multi-breadbasket failures. Last year, the IPCC found that

unless we reduce our emissions levels by five times their current amount, we could hit 1.5°C as early as 2030, and no later than mid-century. This would dramatically increase the risk of simultaneous crop failures, food production shocks and other devastating climate impacts.

In April this year, the

European Commission’s European Strategy and Policy Analysis System published its second major report to EU policymakers, Global Trends to 2030: Challenges and Choices for Europe. The report, which explores incoming national security, geopolitical and socio-economic risks, concluded: “An increase of 1.5 degrees is the maximum the planet can tolerate; should temperatures increase further beyond 2030, we will face even more droughts, floods, extreme heat and poverty for hundreds of millions of people; the likely demise of the most vulnerable populations—

and at worst, the extinction of humankind altogether.”

But the IPCC’s newer models suggest that

the situation is even worse than previously thought. Based on increased supercomputing power and sharper representations of weather systems, those new climate models—presented at a press conference in Paris in late September—reveal the latest findings of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report now underway.

The models now show that

we are heading for 7°C by the end of the century if carbon emissions continue unabated, two degrees higher than last year’s models. This means

the earth is far more sensitive to atmospheric carbon than previously believed.

This suggests that

the climate models we've been using are not too alarmist; they are consistently too conservative, and we have only recently understood how bad the situation really is.

I spoke to Dr. Joelle Gergis, a lead author on the IPCC’s sixth assessment report, about the new climate models. Gergis admitted that at least eight of the new models being produced for the IPCC by scientists in the US, UK, Canada and France suggest a much higher climate sensitivity than older models of 5°C or warmer. But she pushed back against the idea that these findings prove the inevitability of collapse, which she criticized as outside the domain of climate science. Rather, the potential implications of the new evidence are not yet known.

“Yes, we are facing alarming rates of change and

this raises the likelihood of abrupt, non-linear changes in the climate system that may cause tipping points in the Earth’s safe operating space,” she said. “But we honestly don’t know how far away we are from that just yet. It may also be the case that

we can only detect that we’ve crossed such a threshold after the fact.”

In an article published in August in the Australian magazine The Monthly, Dr. Gergis wrote: “When these results were first released at a climate modelling workshop in March this year, a flurry of panicked emails from my IPCC colleagues flooded my inbox. What if the models are right? Has the Earth already crossed some kind of tipping point? Are we experiencing abrupt climate change right now?”

Half the Great Barrier Reef’s coral system has been wiped out at current global average temperatures which are now hovering around 1°C higher than pre-industrial levels. Gergis describes this as “

catastrophic ecosystem collapse of the largest living organism on the planet.” At 1.5°C, between 70 and 90 percent of reef-building corals are projected to be destroyed, and at 2°C, some 99 percent may disappear: “

An entire component of the Earth’s biosphere—our planetary life support system—would be eliminated. The knock-on effects on the 25 percent of all marine life that depends on coral reefs would be profound and immeasurable…

The very foundation of human civilization is at stake.”

But Gergis told me that despite the gravity of the new models, they do not prove conclusively that past emissions will definitely induce collapse within the next decade.

“While we are undeniably observing rapid and widespread climate change across the planet, there is no concrete evidence that suggests we are facing ‘an inevitable, near term society collapse due to climate change,’” she said. “Yes, we are absolutely hurtling towards conditions that will create major instabilities in the climate system, and time is running out, but I don’t believe it is a done deal just yet.”

Yet

it is precisely the ongoing absence of strong global policy that poses the fatal threat. According to Lund University climate scientist Wolfgang Knorr, the new climate models mean that practically implementing the Paris Accords target of keeping temperatures at 1.5 degrees is now extremely difficult. He referred me to his new analysis of the challenge published on the University of Cumbria’s ILFAS blog, suggesting that

the remaining emissions budget given by the IPCC “will be exhausted at the beginning of 2025.” He also noted that

past investment in fossil-fuel and energy infrastructure alone will put us well over that budget.

[MW: and recall the earlier point that new climate science has determined that earth climate sensitivity is greater than previously believed, so those carbon budget estimates were predicated on overly-optimistic assumptions... i.e. our remaining carbon budget to avoid +2C is quite likely to be closer to 0, given that GhGs in atmosphere are now higher than has been the case for millions of years]

The scale of the needed decarbonization is so great and so rapid, according to

Tim Garrett, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah, that

civilization would need to effectively “collapse” its energy consumption to avoid collapsing due to climate catastrophe. In a 2012 paper in Earth System Dynamics, he concluded therefore that

“civilization may be in a double-bind.”

"We still have time to try and avert the scale of the disaster, but we must respond as we would in an emergency"

In a previous paper in Climatic Change, Garrett calculated that the world would need to switch to non-carbon renewable energy sources at a rate of about 2.1 percent a year just to stabilize emissions. “That comes out [equivalent] to almost one new nuclear power plant per day,” Garrett said. Although he sees this as

fundamentally unrealistic, he concedes that a crash transition programme might help: “If society invests sufficient resources into alternative and new, non-carbon energy supplies, then perhaps it can continue growing without increasing global warming.”

Gergis goes further, insisting that it is not yet too late: “We still have time to try and avert the scale of the disaster, but we must respond as we would in an emergency. The question is, can we muster the best of our humanity in time?”

There is no straightforward answer to this question. To get there,

we need to understand not just climate science, but the nature, dynamics, and causes of civilizational collapse.

Limits to Growth

One of the most famous scientific forecasts of collapse was conducted nearly 50 years ago by a team of scientists at MIT. Their "

Limits to Growth" (LTG) model, known as "World3," captured the interplay between exponential population and economic growth, and the consumption of raw materials and natural resources. Climate change is an implicit feature of the model.

LTG implied that

business-as-usual would lead to civilizational breakdown, sometime between the second decade and middle of the 21st century,

due to overconsumption of natural resources far beyond their rate of renewal. This would escalate costs, diminish returns, and accelerate environmental waste, ecosystem damage, and global heating. With more capital diverted to the cost of extracting resources, less is left to invest in industry and other social goods, driving long-term economic decline and political unrest.

The forecast was widely derided when first published, and its core predictions were often wildly misrepresented by commentators who claimed it had incorrectly forecast the end of the world by the year 2000 (it didn’t).

Systems scientist

Dennis Meadows had headed up the MIT team which developed the ‘World3’ model. Seven years ago, he updated the original model in light of new data with co-author

Jorgen Randers, another original World3 team-member.

“For those who respect numbers, we can report that the highly aggregated scenarios of World3 still appear… to be surprisingly accurate,” they wrote in Limits to Growth: the 30 year update. “The world is evolving along a path that is consistent with the main features of the scenarios in LTG.”

One might be forgiven for suspecting that the old MIT team were just blowing their own horn. But a range of independent scientific reviews, some with the backing of various governments, have repeatedly confirmed that

the LTG ‘base scenario’ of overshoot and collapse has continued to fit new data. This includes studies by Professor

Tim Jackson of the University of Surrey, an economics advisor to the British government and Ministry of Defense; Australia’s federal government scientific research agency CSIRO; Melbourne University’s Sustainable Society Institute; and the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries in London.

“Collapse is not a very precise term. It is possible that there would be a general, drastic, uncontrolled decline in population, material use, and energy consumption by 2030 from climate change," Meadows told me when I asked him whether the LTG model shines any light on the risk of imminent collapse. "But I do not consider it to be a high probability event,” he said. Climate change would, however, “certainly suffice to alter our industrial society drastically by 2100.” It could take centuries or millennia for ecosystems to recover.

But there is a crucial implication of the LTG model that is often overlooked: what happens during collapse. During an actual breakdown, new and unexpected social dynamics might come into play which either worsen or even lessen collapse.

Those dynamics all depend on human choices. They could involve positive changes through reform in political leadership or negative changes such as regional or global wars.

That’s why modelling what happens during the onset of collapse is especially tricky, because the very process of collapse alters the dynamics of change.

Growth, complexity and resource crisis

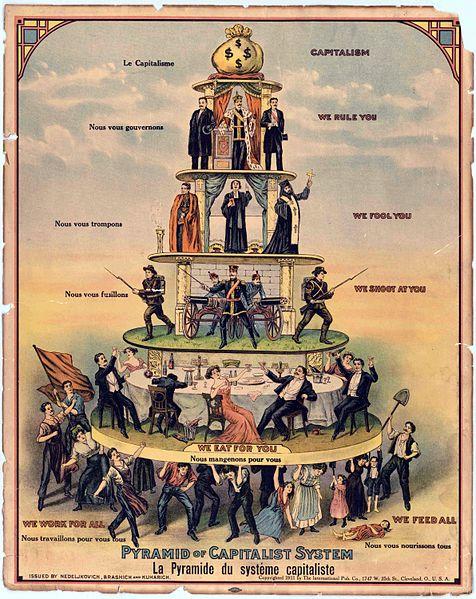

What if, then, collapse is not necessarily the end? That’s the view of

Ugo Bardi, of the University of Florence, who has developed perhaps the most intriguing new scientific framework for understanding collapse.

Earlier this year, Bardi and his team co-wrote a paper in the journal BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, drawing on the work of anthropologist

Joseph Tainter at Utah State University’s Department of Environment and Society. Tainter’s seminal book,

The Collapse of Complex Societies, concluded that societies collapse when their investments in social complexity reach a point of diminishing marginal returns.

Tainter studied the fall of the Western Roman empire, Mayan civilization, and Chaco civilization. As societies develop more complex and specialized bureaucracies to solve emerging problems, these new layers of problem-solving infrastructure generate new orders of problems. Further infrastructure is then developed to solve those problems, and the spiral of growth escalates.

As each new layer also requires a new ‘energy’ subsidy (greater consumption of resources), it eventually cannot produce enough resources to both sustain itself and resolve the problems generated. The result is that society collapses to a new equilibrium by shedding layers of complex infrastructure amassed in previous centuries. This descent takes between decades and centuries.

In his recent paper, Bardi used computer models to test how Tainter’s framework stood-up. He found that diminishing returns from complexity were not the main driver of a system’s decline; rather the decline in complexity of the system is due to diminishing returns from exploiting natural resources.

In other words,

collapse is a result of a form of endless growth premised on the unsustainable consumption of resources, and the new order of increasingly unresolvable crises this generates.

In my view,

we are already entering a perfect storm feedback loop of complex problems that existing systems are too brittle to solve. The collapse of Syria, triggered and amplified partly by climate crisis, did not end in Syria. Its reverberations have not only helped destabilize the wider Middle East, but contributed to the destabilization of Western democracies.

In January, a study in Global Environment Change found that the impact of “climatic conditions” on “drought severity” across the Middle East and North Africa amplified the “likelihood of armed conflict.” The study concluded that climate change therefore played a pivotal role in driving the mass asylum seeking between 2011 and 2015—including the million or so refugees who arrived in Europe in 2015 alone, nearly 50 percent of whom were Syrian. The upsurge of people fleeing the devastation of their homes was a gift to the far-right, exploited by British, French and other nationalists campaigning for the break-up of the European Union, as well as playing a role in Donald Trump’s political campaigning around The Wall.

To use my own terminology, Earth System Disruption (ESD) is driving Human System Destabilization (HSD). Preoccupied with the resulting political chaos, the Human System becomes even more vulnerable and incapable of ameliorating ESD. As ESD thus accelerates, it generates more HSD. The self-reinforcing cycle continues, and we find ourselves in an amplifying feedback loop of disruption and destabilization.

Beyond collapse

Is there a way out of this self-destructive amplifying feedback loop? Bardi’s work suggests there might be—that

collapse can pave the way for a new, more viable form of civilization, whether or not countries and regions experience collapses, crises, droughts, famine, violence, and war as a result of ongoing climate chaos.

Bardi’s analysis of Tainter’s work extends the argument he first explored in his 2017 peer-reviewed study,

The Seneca Effect: When Growth is Slow but Collapse is Rapid. The book is named after the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, who once said that “fortune is of sluggish growth, but ruin is rapid.”

Bardi examines a wide-range of collapse cases across human societies (from the fall of past empires, to financial crises and large-scale famines), in nature (avalanches) and through artificial structures (cracks in metal objects). His verdict is that collapse is not a “bug,” but a “varied and ubiquitous phenomena” with multiple causes, unfolding differently, sometimes dangerously, sometimes not. Collapse also often paves the way for the emergence of new, evolutionary structures.

In an unpublished manuscript titled

Before the Collapse: A Guide to the Other Side of Growth, due to be published by science publisher Springer-Nature next year, Bardi’s examination of the collapse and growth of human civilizations reveals that after collapse, a "Seneca Rebound" often takes place in which new societies grow, often at a rate faster than preceding growth rates.

This is because collapse eliminates outmoded, obsolete structures, paving the way for new structures to emerge which often thrive from the remnants of the old and in the new spaces that emerge.

He thus explains the Seneca Rebound as “as an engine that propels civilizations forward in bursts. If this is the case, can we expect a rebound if the world’s civilization goes through a new Seneca Collapse in the coming decades?”

Bardi recognizes that the odds are on a knife-edge. A Seneca Rebound after a coming collapse would probably have different features to what we have seen after past civilizational collapses and might still involve considerable violence, as past new civilizations often did—or may not happen at all.

On our current trajectory, he said, “the effects of the destruction we are wreaking on the ecosystem could cause humans to go extinct, the ultimate Seneca Collapse.” But if we change course, even if we do not avoid serious crises, we might lessen the blow of a potential collapse. In this scenario, “the coming collapse will be just one more of the series of previous collapses that affected human civilizations: it might lead to a new rebound.”

It is in this possibility that Bardi sees the seeds of a new, different kind of civilization within the collapse of civilization-as-we-know-it.

I asked Bardi how soon he thought this collapse would happen. Although emphasizing that collapse is not yet inevitable, he said that

a collapse of some kind within the next decade could be “very likely” if business-as-usual continues.

“

Very little if anything is being done to stop emissions and the general destruction of the ecosystem,” Bardi said. “

So, an ecosystemic collapse is not impossible within 10 years."

Yet he was also careful to point out that the worst might be avoided: “On the other hand, there are many elements interacting that may change things a little, a lot, or drastically. We don’t know how the system may react… maybe the system would react in a way that could postpone the worst.”

Release and renewal

The lesson is that even if collapse is imminent, all may not be lost. Systems theorist Jeremy Lent, author of The Patterning Instinct, draws on the work of the late University of Florida ecologist C. S. Holling, whose detailed study of natural ecosystems led him to formulate a general theory of social change known as the adaptive cycle.

Complex systems, whether in nature or in human societies, pass through four phases in their life cycle, writes Lent. First is a rapid growth phase of innovation and opportunity for new structures; second is a phase of stability and consolidation, during which these structures become brittle and resistant to change; third is a release phase consisting of breakdown, generating chaos and uncertainty; the fourth is reorganization, opening up the possibility that small, seemingly insignificant forces might drastically change the future of the forthcoming new cycle.

It is here, in the last two phases, that the possibility of triggering and shaping a Seneca Rebound becomes apparent. The increasing chaos of global politics, Lent suggests, is evidence that we are “entering the chaotic release phase,” where the old order begins to unravel. At this point, the system could either regress, or it could reorganize in a way that enables a new civilizational rebound. “This is a crucially important moment in the system’s life cycle for those who wish to change the predominant order.”

So as alarming as the mounting evidence of the risk of collapse is, it also indicates that we are moving into a genuinely new and indeterminate phase in the life cycle of our current civilization, during which we have a radical

opportunity to mobilize the spread of new ideas that can transform societies.

I have been tracking the risks of collapse throughout my career as a journalist and systems theorist. I could not find any decisive confirmation that climate change will inevitably produce near-term societal collapse.

But the science does not rule this out as a possibility. Therefore,

dismissing the risk of some sort of collapse—whether by end of century, mid-century, or within the next 10 years—contravenes the implications of the most robust scientific models we have.

All the scientific data available suggests that if we continue on our current course of resource exploitation, human civilization could begin experiencing collapse within coming decades. Exactly where and how such a collapse process might take off is not certain; and whether it is already locked in is as yet unknown. And as NASA’s Gavin Schmidt told me, local collapses are already underway.

From Syria to Brexit, the destabilizing socio-political impacts of ecosystemic collapse are becoming increasingly profound, far-reaching and intractable. In that sense, debating whether or not near-term collapse is inevitable overlooks the stark reality that we are already witnessing climate collapse.

And yet, there remains an almost total absence of meaningful conversation and action around this predicament, despite it being perhaps the most important issue of our times.

The upshot is that we don’t know for sure what is round the corner, and we need better conversations about how to respond to the range of possibilities. Preparation for worst-case scenarios does not require us to believe them inevitable, but vindicates the adoption of a rational, risk-based approach designed to proactively pursue the admirable goal for Deep Adaptation: safeguarding as much of society as possible.

Jem Bendell’s Deep Adaptation approach, he told me, is not meant to provide decisive answers about collapse, but to catalyze conversation and action.

“For the Deep Adaptation groups that I am involved with, we ask people to agree that societal collapse is either likely, inevitable or already unfolding, so that we can have meaningful engagement upon that premise,” he said. “Deep Adaptation has become an international movement now, with people mobilizing to share their grief, discuss what to commit to going forward, become activists, start growing food, all kinds of things.”

Confronting the specter of collapse, he insisted is not grounds to give-up, but to do more. Not later, but right now, because we are already out of time in terms of the harm already inflicted on the planet: “My active and radical hope is that we will do all kinds of amazing things to reduce harm, buy time and save what we can," he said. "Adaptation and mitigation are part of that agenda. I also know that many people will act in ways that create more suffering."

Most of all, the emerging science of collapse suggests that civilization in its current form, premised on endless growth and massive inequalities, is unlikely to survive this century. It will either evolve into or be succeeded by a new configuration, perhaps an “ecological civilization”, premised on a fundamentally new relationship with the Earth and all its inhabitants—or it will, whether slowly or more abruptly, regress and contract.

What happens next is still up to us. Our choices today will not merely write our own futures, they determine who we are, and what our descendants will be capable of becoming. As we look ahead, this strange new science hints to us at a momentous opportunity to become agents of change for an emerging paradigm of life and society that embraces, not exploits, the Earth.

Because doing so is now a matter of survival.

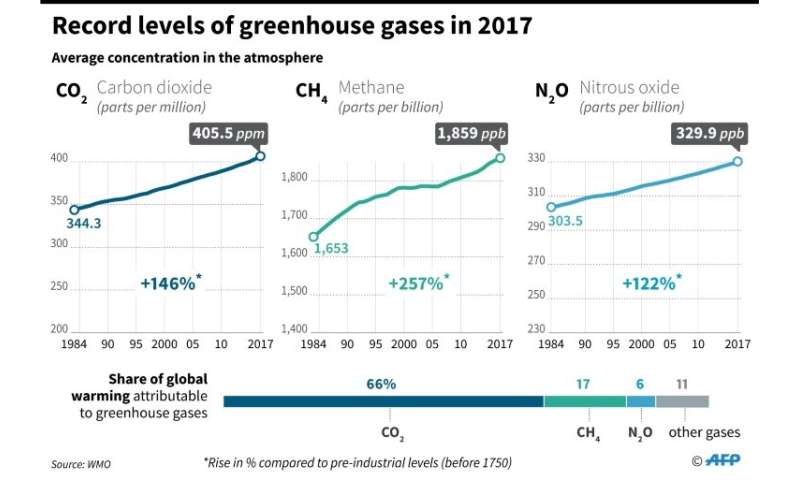

The last time there was so much CO2 in Earth's atmosphere, ice caps virtually disappeared

The last time there was so much CO2 in Earth's atmosphere, ice caps virtually disappeared Change in levels of CO2, methane and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere since 1984

Change in levels of CO2, methane and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere since 1984 Manmade emissions on the other hand have added some 120 ppm of CO2 in a little over a century and a half

Manmade emissions on the other hand have added some 120 ppm of CO2 in a little over a century and a half