How to Avoid Population Overshoot and Collapse. Michael Mills, Psychology Today. Nov. 2, 2011.

Manipulating psychological adaptations to help to prevent ecological overshoot.

"All species expand as much as resources allow and predators, parasites, and physical conditions permit. When a species is introduced into a new habitat with abundant resources that accumulated before its arrival, the population expands rapidly until all the resources are used up."

- David Price, Energy and Human Evolution

Life scientists are aware of the concept of ecological "carrying capacity" (the maximum population that can be supported by the environment) and Malthus' application of these ideas to human populations. Malthus wrote:

"It is an obvious truth, which has been taken notice of by many writers, that population must always be kept down to the level of the means of subsistence; but no writer that the Author recollects has inquired particularly into the means by which this level is effected..." Thomas Malthus, 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population

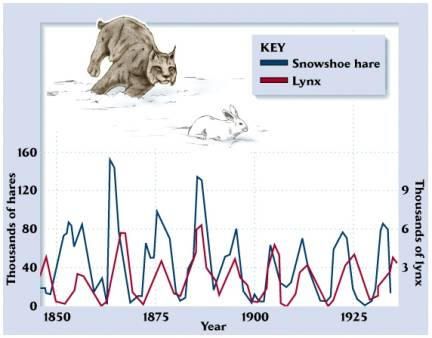

Often, there is a cyclical relationship between the populations of predators and their prey. This keeps the populations of both species in check.

But, what happens when there are no predators?

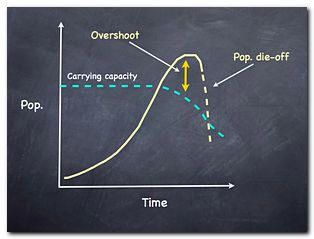

This issue was addressed in a paper by David Klein, "The Introduction, Increase and Crash of Reindeer on St. Matthew Island." Klein reported that in 1944, 29 reindeer were brought to St. Matthew Island. Initially there were abundant food sources, and the reindeer population increased dramatically. There were no predators to cull the population.

About 20 years after they were first introduced, the reindeer had overshot the food carrying capacity of the island, and there was a sudden, massive die-off. About 99% of the reindeer died of starvation.

Source: http://dieoff.org/page80.htm

As shown in the graph below, this is an example of a general phenomenon. All species suffer population collapse or species extinction if they overshoot and degrade the carrying capacity of their ecology.

This is also the fate that awaits bacteria growing in a Petri dish, as you might remember from your high school biology course. Imagine a Petri dish with enough nutrients to support a growing bacteria culture until the dish is completely full of them. One bacterium is placed inside the dish at 11:00am, and the population of bacteria doubles every minute -- such that the Petri dish will be full by noon.

At what time will the Petri dish be half full of bacteria?

Most people reply incorrectly that the Petri dish will be half full at 11:30am, because we are more familiar with linear, rather than with exponential, rates of growth. The correct answer is 11:59am -- which seems rather unintuitive. However, because the rate of growth is exponential (doubling every minute) the time at which the Petri dish is half full is 11:59am. With just one more doubling, in the next minute, the Petri dish is completely full, at noon.

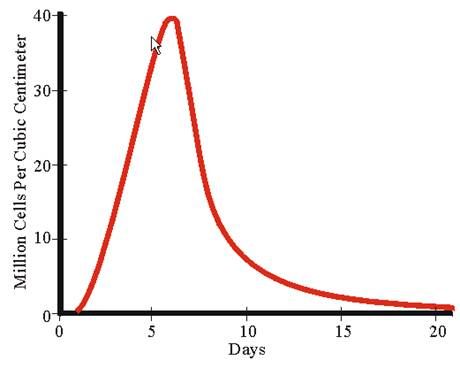

Below is another example of a population overshoot and collapse scenario. This is the population graph of yeast cells in a 10% sugar solution. Note that the yeast population first explodes exponentially, and is then followed by population die-off as the finite nutrients are exhausted and their own waste products pollute their environment.

This is how yeast turns grape juice into wine. The next time you say "cheers" over a glass of wine, remember that you are drinking the waste products (alcohol) of a collapsed yeast colony with poor ecological management skills!

Anyone who perceives a linear rate of growth, but who is actually up against an exponential rate of growth, is likely to be very surprised at how the end comes very quickly and seemingly out of nowhere. They will be completely blindsided.

For more information about the dangers of exponential growth, I highly recommend the video Arithmetic, Population and Energy, by Prof. Albert Bartlett. The key point to remember about Professor Bartlett's lecture: "The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function."

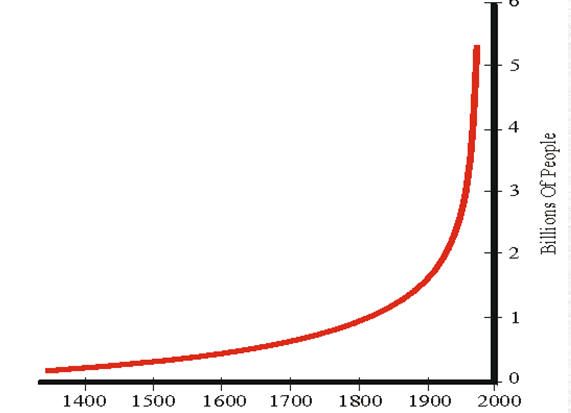

Notice how human population has also been on an exponential trend:

Are we humans smarter than yeast? Or will the graphic above of our population follow the overshoot and collapse graphic of the yeast? Unlike yeast, do we have any evolved psychological adaptations to help us to identify and avoid ecological overshoot?

The fate of humans on Easter Island may help to provide an answer. When the first humans arrived on the island, there were abundant resources to support the small population. Just like the yeast and the reindeer, the human population increased dramatically. There were no predators to cull the population. The human population continued to grow until it eventually overshot the island carrying capacity. After overshoot, most of the population starved. Apparently, they even turned on each other, sometimes resorting to cannibalism.

Human ecological exceptionalism?

It will be a race toward either paradise or oblivion, right to the last moment. -- Buckminster Fuller

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe. -- H.G. Wells, The Outline of History

At this point, many people refer to human exceptionalism. Of course we are smarter than yeast or reindeer, and our scientific advances and our technology will save us from ecological overshoot. We can expand the carrying capacity of the Earth.

Raymond Kurzweil has argued in his 2005 book The Singularity is Near that scientific knowledge, like populations, also grows exponentially. He believes that this will allow us to expand the Earth's ecological carrying capacity, cure disease and aging, and solve problems of energy depletion. He is confident that technology will help us prevent ecological overshoot and population collapse.

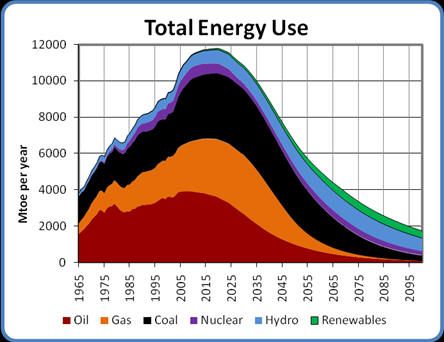

So, we have two opposing, exponentially increasing trends. One exponential trend leads to ecological overshoot and collapse; the other trend could lead to scientific/technological solutions to these problems. Which will arrive first? Ecological overshoot and collapse (Malthus), or a "techno-fix" (Kurzweil)? No one knows. But, we probably won't have to wait long to find out. One of these two scenarios will likely occur within the next several decades. But, which one? Generally it is healthy to be optimistic, but optimism can be deadly if it produces a Pollyannaish denial of real problems. We should not ignore ecological problems by assuming "someone else" will take care of it, or that "the free market" or "technological breakthroughs" will always come to the rescue in time. Solutions may not come in time, and we may get quite a rude Malthusian smack down later. To avoid this, one problem we must face is how to make the transition from our finite, depleting oil resources to renewable energy. Technological civilization depends on cheap, abundant energy.

Peak oil as an example of human ecological overshoot.

There is no substitute for energy. The whole edifice of modern society is built upon it. It is not "just another commodity" but the precondition of all commodities, a basic factor equal with air, water and earth.

-- E. F. Schumacher (1973)

We know that we cannot sustain a future powered by a fuel that is rapidly disappearing. ...breaking our oil addiction is one of the greatest challenges our generation will ever face. ...This will not be easy.

-- Barack Obama, August 4, 2008

One example of resource depletion is the gradual depletion of fossil fuels, especially oil. The amount of oil produced by a particular oil field, or a region, shows a regular pattern: first oil production increases, then it reaches a peak, and, finally, as the oil field begins to dry up, oil production starts to decline. World "peak oil" is when world oil production peaks, and then starts an inexorable decline as oil fields start to dry up. Many experts believe that world oil production has already peaked, or that it will occur within the next few years. This presents us with a problem: as of now, no combination of renewable energy sources can scale up quickly enough, or provide anywhere near the energy equivalent of oil. We can anticipate that the world is about to enter a severe, worldwide energy shortage. Since food production is so dependent on energy production, following an energy famine will be a food famine. Many poor people, especially in developing countries, will literally starve to death as oil energy depletes.

Unless scientists discover some energy breakthrough "miracle" that can provide scalable and energy dense renewable energy, the predictions made in the graphs below paint some very grim scenarios. As you review these graphs, keep in mind that these nightmares are not in some distant future. They may arrive in less than one or two decades from now.

Here is a brief video of the history of human energy consumption, and the energy challenges we will soon be facing.

General human ecological overshoot

The 1972 book Limits to Growth also made some pretty frightening predictions back in 1972, as did the follow-up book in 2004 Limits to Growth: The 30 Year Update. Using computer simulations, they predicted a world peak population around mid-century, followed by population decline.

Given that these predictions are now approaching 40 years old, how accurate were they? Are they still on track today?

In an article published in Science titled "Revisiting the Limits to Growth After Peak Oil," Hall and Day noted that "the values predicted by the limits-to-growth model and actual data for 2008 are very close." These findings are consistent with another study titled "A Comparison of the Limits of Growth with Thirty Years of Reality" which concluded: "The analysis shows that 30 years of historical data compares favorably with key features... [of the Limits to Growth] 'standard run' scenario, which results in collapse of the global system midway through the 21st Century." To prevent this scenario, the Limits to Growth authors suggested that we must achieve ecological sustainability by 2022 to avoid serious ecological overshoot and population collapse.

Can evolutionary psychology provide insights to aid in our survival?

Can humans be "smarter than yeast?" Can we be the only species that can successfully anticipate and avoid ecological overshoot and collapse? Issues of sustainability are psychological problems. Are we sufficiently psychologically sophisticated to manage our own collective behavior to achieve sustainability on a finite planet?

One sobering answer provided by evolutionary psychology is that we, like all other species, have no evolved psychological adaptations designed specifically to perceive, anticipate and avoid ecological overshoot. In fact, we have just the opposite.

One problem is that inclusive fitness, the "designer" of psychological adaptations, is always relative to others; it is not absolute. That is, nature doesn't "say," "Have two kids (or help 4 full sibs), and then you can stop. Good job! You did your genetic duty, you avoided contributing to ecological overshoot, and you may pass along now..." Instead, nature "says" (relative inclusive fitness): "Out-reproduce your competitors. Your competitors are all of the genes in your species' gene pool that you do not share. If the average inclusive fitness score is four, then you go for five... "In other words, our psychological adaptations are designed to not just "keep up with the Joneses" but to "do better than the Joneses." This is in whatever means that may have generally helped to increase inclusive fitness, such as status, conspicuous consumption, and resource acquisition and control.

If we are to have a fighting chance to be "smarter than yeast," we have to out-smart our own psychological adaptations; we have to "fool Mother Nature." Garrett Harden recognized that the problem of ecological overshoot is the tragedy of the commons writ large. He suggested that the way to solve the tragedy of the commons was "mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon by the majority of the people affected." That is, we must consent, collectively, to use our knowledge of our psychological adaptations to tweak them in the service of sustainability.

For example, we can use such knowledge to manipulate our own perceptions of status so that we actually compete to reduce our consumption of finite resources, such that we compete to "keep down with the Joneses."

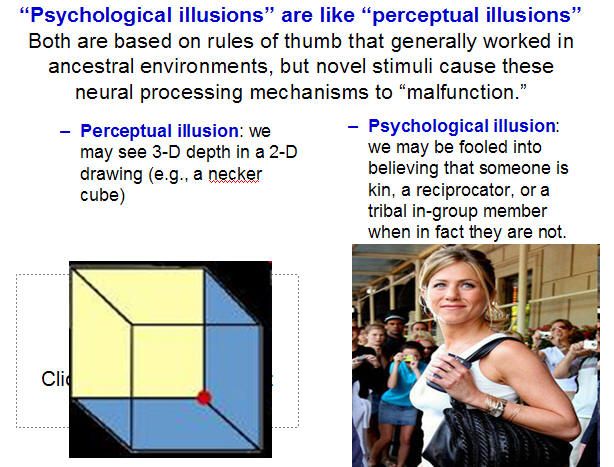

Psychologist Robert Cialdini has investigated the use of "psychological illusions" to persuade people to do things they otherwise might be disinclined to do. Here is one description of Cialdini's approach (from: "Finding the 'Weapons' of Persuasion to Save Energy"):

In one San Diego suburb, Cialdini's team went door to door, ringing the doorknobs with signs about energy conservation. There were four types of signs, and each home received one randomly, every week, ...for a month. The first sign urged the homeowner to save energy for the environment's sake; the second said to do it for future generations' benefit. The third sign pointed to the cash savings that would come from conservation. The fourth sign featured Cialdini's trick: "The majority of your neighbors are undertaking energy saving actions every day." ...(Cialdini also) decided to target the below-average energy users with a special message. "When we sent them the message saying you're doing better than your neighbors, we put a smiley face emoticon next to their score," he said. "And that kept them down below what any of their neighbors were doing."

Note how this psychological manipulation helped to redefine high status to "keeping down with the Joneses."

In addition, women may have a special role to play to promote sustainability. Women need to be prepped to find "ecological men" of limited resource consumption really, really sexy. Unfortunately, sexual selection has designed women to tend to prefer "alpha males" -- high status, high consumption, high resource control men (in ancestral times, they helped women's children survive and thrive). Men are adapted to do their best to give women what they want, or face reproductive oblivion. One way that today's men have demonstrated their high status has been to drive big sport utility vehicles (SUVs). However, what if women's psychological adaptations were manipulated (with collective consent) such that they found the guy behind the wheel of an electric car, electric scooter, or, better yet, a bicycle, irresistible? And, what if women sexually rejected the guy driving a big, gas-guzzling SUV?

Our natural tendencies toward nepotism and favoritism also militate against solving the ecological tragedy of the commons. Evolutionary psychology suggests that, when it comes to sharing valuable resources, especially those that are depleting, we will tend to be most altruistic to close genetic kin (inclusive fitness). We may play nice with non-kin if we have established an on-going, mutually beneficial reciprocal relationship (reciprocity). On the negative side, when the above conditions are not met, evolutionary psychology suggests that we will tend to act selfishly. We may even be spiteful (hurt others even at a cost to self) to reduce the relative inclusive fitness of others, especially when competition is increasing because the overall resource pie is shrinking.

But evolutionary psychology also suggests that we might cooperate with people that we identify as part of our "tribe" (strong reciprocity). This feature of human nature may be one of the keys to our ecological survival. Today, the capacity to be altruistic to in-group strangers may result from a serendipitous generalization (or "mismatch") between ancestral tribal living and today's large societies that entail many single interactions with anonymous strangers. Due to this mismatch, we may be fooled into thinking members of our society are part of our "tribe." Result: strong reciprocity -- acting like a "good Samaritan," cognitive concepts of justice, ethics and human rights, and a willingness to conserve finite depleting resources.

However, such strong reciprocity is more likely to occur in a "positive sum game," when the entire resource pie is growing. An individual simply has to cooperate with social rules to expect a progressively larger slice of the pie in the future. So strong reciprocity works well when the overall resource pie is growing (in a "positive sum game"). But, the world-wide depletion of finite resources is a "shrinking pie" situation (a "negative sum game"). Sustainable management of limited Earth resources requires that the whole world cooperate as these resources dwindle.

Such cooperation may be encouraged by using virtual reality to manipulate our psychological adaptations. Today we can enjoy films, TV, and photos precisely because they were not part of our ancestral environment. We have no adaptations to counter these novel tricks - at some unconscious psychological levels we cannot distinguish between reality and virtual reality.

For example, when we watch a TV sitcom, such as Friends, we are fooled (at least on an emotional level) into thinking the characters really are our friends. We may smile and say hello if we see Jennifer Aniston on the street because virtual reality tricked us into believing that we really are friends.

We cry and laugh at movies, despite the fact that we know what we are watching is just light projected through film, the actors are reciting from a script, and there is a sound guy holding a boom mic standing just out of the frame. Sure, it is sad that the ship sank, but no one on the set actually drowned. Nevertheless, our psychological adaptations are fooled, and we may leave the theater a bit misty.

So just as we can be fooled by perceptual illusions, we can also be fooled (and psychologically manipulated) by virtual reality illusions. By mutual consent, we could use virtual reality to intentionally trick ourselves into perceiving that everyone on the planet is a member of our "tribe," that the Earth is our tribal territory that needs to be defended and protected, and that we need to conserve and fairly share finite resources.

For example, we could collectively consent to allow Public Service Announcements (PSAs) - virtual reality media advertisements -- to tweak our psychological adaptations. PSAs have been effective to reduce other self-destructive behaviors, such as smoking. PSAs could help to develop a strong social narrative of mutual cooperation and sustainability on a finite planet.

Needed: A sustainability movement

A new social movement is needed - a sustainability movement. This is particularly important for anyone who plans to live in the future. A grass-roots movement of the magnitude of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and the women's rights movement of the 1970s, is needed. Today no one wants to be called a racist or a sexist (but being called a "consumerist" does not yet sting). Those movements had clearly defined out-groups to vilify as the "enemy" -- and that may have helped to mobilize and motivate activists.

But who is the enemy now? There is no out-group. The enemy is us. We are fighting against ourselves -- our base psychological adaptations to compete for relative status, mates and resources. Evolutionary psychology can help by identifying which of our "psychological buttons" might be manipulated to promote sustainability. But we must collectively agree to manipulate our psychological adaptations to attempt to "transcend" our self-ecocidal nature. If we succeed, there may be a glimmer of hope of mitigating our own ecological overshoot, and the potential Malthusian nightmares of the future.

For an expanded exploration of these topics, with a particular emphasis on energy depletion, see my webpage: Evolutionary psychology and peak oil.

References and further reading:

Diamond, J. Collapse. NY: Viking, 2005.

Hall, C. A. S., & Day, J. W. Revisiting the Limits to Growth After Peak Oil. American Scientist, 97 (2009): 230 -238.

Hardin G. The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162 (1968): 1243-1248.

Heinberg, H. Peak Everything: Waking Up to the Century of Declines. NY: New Society Publishers, 2007.

Klein, D. R. The Introduction, Increase and Crash of Reindeer on St. Matthew Island. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 32 (1968): 235-267

Kustler, J. H. The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century. NY: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2005.

Kurzweil, R. The Singularity is Near. NY: Penguin, 2005.

Meadows, D. Limits to growth. NY: Signet, 1972.

Meadows, D. H., Randers, J., & Meadows, D. L. Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. NY: Chelsea Green, 2004.

Rahim, S. Finding the 'weapons' of persuasion to save energy. New York Times, June 21, 2010.

Turner, G. A Comparison of the Limits of Growth with Thirty Years of Reality. CSIRO Working Paper Series, (2010). Available at: http://www.csiro.au/files/files/plje.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment