Another excellent post by Tim Morgan:

#156. Actual fantasy. Tim Morgan, Surplus Energy Economics. October 13, 2019.

OUR URGENT NEED FOR RATIONAL ECONOMICS

Everyone knows the quotation, of course, which says that “when it gets serious, you have to lie”.Actually, when it gets even more serious, we have to face the facts.

I’m indebted to Dutch rock music genius Arjen Lucassen for the observation that the counterpart to “virtual reality” is actual fantasy – and that’s where the world economy seems to be right now.

You may think it’s imminent, or you might believe that it still lies some distance in the future, but I’m pretty sure you know that we’re heading, inescapably, for “GFC II”, the much larger (and very different) sequel to the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC).

SEEDS 20 – the latest iteration of the Surplus Energy Economics Data System – has a new module which calculates the scale of exposure to “value destruction”. This exposure now stands at $320 trillion, compared with $67tn (at 2018 values) on the eve of GFC I at the end of 2007.

How this number is reached, and what it means, can be discussed later. Additionally, potential for value destruction needn’t mean that this is the quantity of value which actually will be destroyed when a crash happens. Rather, it gives us a starting order-of-magnitude.

For now, though, we can simply note that risk exposure seems now to be at least four times what it was back in 2008. Moreover, interest rates, now at or close to zero, cannot be slashed again, as they were in 2008-09. Neither can governments again put their now-stretched balance sheets behind their banking systems, even if global interconnectedness didn’t render such actions by individual countries largely ineffective.

Finally – in this litany of risk – two further points need to be borne in mind. First, global prosperity is weakening, and has been falling in most Western economies for at least a decade, so any new crash will test an already-weakened economic resilience.

Second, and relatedly, any attempt to repeat the rescues of 2008 would be unlikely to be accepted by a general public which now – and, in general, correctly – characterises those rescues as ‘bail-outs for the wealthy, and austerity for everyone else’.

The high price of ignorance

It’s tempting – looking at a world divided between struggling, often angry majorities, and tiny minorities rich beyond the dreams of avarice – to think the surreal state of the world’s financial system reflects some grand scheme, driven by greed. Alternatively, you might feel that far too many countries are run by people who simply aren’t up to the job.

Ultimately, though – and whilst greed, arrogance, incompetence and ambition have all been present in abundance – the factor driving most of what has gone wrong in recent years has been simple ignorance. For the most part, disastrous decisions have been made in good faith, because thinking has been conditioned by the false paradigm which states that ‘economics is the study of money’, and which adds, to compound folly still further, that energy is ‘just another input’.

I don’t want to labour a point familiar to most regular readers, so let’s wrap up recent history very briefly.

From the late 1990s, as “secular stagnation” kicked in (for reasons which very few actually understood, then or now), the siren voices of conventional economics argued that this could be ‘fixed’ by making it easier for people to borrow than it had ever been before. This created, not just debt escalation, but a lethal proliferation and dispersal of risk, which led directly to 2008.

In response, the same wise people, those whose insights caused the crisis in the first place, now counselled yet more bizarre gimmicks, the worst of which was that we should pay people to borrow, whilst simultaneously destroying the ability to earn returns on capital. Nobody seems to have wondered (still less explained) how we were supposed to operate a capitalist economy without returns on capital – and that, by the way, is why what we have now isn’t remotely a capitalist system based on properly-functioning markets.

When GFC II turns up, it’s as predictable as night following day that the zealots of the ‘economics is money’ fraternity will come up with yet more hare-brained follies. We already know what some of these are likely to be. There are certain to be strident calls for yet more money creation (but this time with a label saying that “it’s not QE – honest”). Some will advocate ‘helicopter money’, perhaps calling it ‘peoples’ QE’. There will be calls for negative nominal interest rates, with the necessary concomitant of the banning of cash. Ideas even more barking mad than these are likely to turn up, too.

Ultimately, what’s likely to happen is that the authorities will respond to GFC II by pouring into the system more additional money than the credibility of fiat currencies can withstand.

We know, of course, that any new gimmicks, just like the old ones, won’t ‘fix’ anything, and can be expected to make a bad situation even worse.

So the question facing everyone now – but especially decision-makers in government, business and finance, and those who influence their decisions – is whether we abandon conventional economics before, or after, the next mad turn of the roulette wheel.

Put another way, should the creators of “deregulation”, QE and ZIRP – and the facilitators of sub-prime and “cash-back” mortgages, collateralised debt obligations and the alphabet soup of “financial weapons of mass destruction” – be allowed to introduce yet more insanity into the system?

Before making this decision, there’s one further point that everyone needs to bear in mind. In 2008, financial gimmickry nearly, but not quite, destroyed the banking system. The only reason why this didn’t happen was that fiat money retained its credibility. But, whilst the follies which preceded the GFC imperilled only the credit (banking) system, those which have followed have put the credibility of money itself at risk.

This is perhaps the most powerful reason of all for not letting the practitioners of ‘conventional’ economics have another swing at the wrecking-ball.

I hope that, reflecting on this, you’ll agree with me that we can no longer afford the folly of financial economics.

Moreover, we need to say so, making fundamental points forcefully, and resisting any temptation to wander off into esoteric by-ways.

A scientific alternative?

If there can be no doubt at all that money-based interpretation of the economy has ended in abject failure, there can be very little doubt that a workable alternative is ready and waiting. That alternative is the recognition that the economy is an energy system.

This idea is by no means a new one and, though I’d prefer not to particularize, it’s been pioneered by some truly brilliant people. If those of us who base our interpretations on the energy-economics paradigm can see a long way into the future, it’s because we’re “standing on the shoulders of giants”.

Moreover, much of the work of the pioneers is rooted in solid science, meaning that, for the first time, there is the prospect of a genuine science of economics, firmly located within the laws of thermodynamics. This has to be a more rational option than continuing to rely on economic ‘laws’ which try to impute immutable patterns to the behaviour of money – something which is, after all, no more, than a human construct.

I like to think that my much more modest role in this direction of travel has been to recognize that, if energy economics is going to transition from the side-lines of the debate to its centre, it needs to tackle conventional economics on its own turf. That means that, whilst as purists we might prefer to set out our findings in calories, BTUs and joules, we have to talk in dollars, euros and yen if we’re to secure a hearing. It also means that we need models of the economy based firmly on energy principles.

If you’re a regular visitor to this site then the basics of what I call surplus energy economics will be familiar. Even so, and with new visitors in mind, a brief summary of its main principles seems apposite.

Core principles

The first principle of surplus energy economics is that everything that constitutes the economy is a function of energy. Literally nothing – goods, services, infrastructure, travel, information – can be supplied without it. Even in the most basic aspects of our lives, everything that we need – including somewhere to live, food and water – is a product of the application of energy. The more complex a society becomes, the more energy it requires, even if this is sometimes masked when energy-intensive activities are outsourced to other countries. The idea that we can somehow “decouple” economic activity from the use of energy has been debunked comprehensively by the European Environmental Bureau as “a haystack without a needle”.

You need only picture a society even temporarily deprived of energy to see the reality of this. Without energy, food cannot be grown, processed or delivered, water fails when the pumps stop working, our homes and places of work become cold and dark, and schools and hospitals cease to function. Without continuity of energy, machinery falls silent, nothing can move from where it is to where it is needed, individuals lose the mobility that we take for granted, and, in a pretty short time, social order fails and chaos reigns.

Ironically, financial systems are amongst the first to collapse when the energy plug is pulled. People cannot even write learned papers telling us that energy is ‘just another input’ when their computer screens have just gone down.

The second principle of surplus energy economics is that, whenever energy is accessed, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. Stated at its simplest, you cannot drill an oil or gas well, excavate a mine, or manufacture a wind turbine or a solar panel without using energy. Much of this energy goes into the provision of materials, of which just one example is copper. This is now extracted at ratios as low as one tonne of copper from five hundred tonnes of rock. Supplying copper, then, cannot be done with human or animal labour – and, of course, even if this were possible, the need for nutritional energy would keep the circular, ‘in-out’ energy linkage wholly in place.

Taken together, these principles dictate a division of available energy into two streams or components.

The first is the energy consumed in the access process, known here as the Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE).

The second – constituting all available energy other than ECoE – is known as surplus energy. This powers all economic activity, other than the supply of energy itself.

This makes ECoE an extremely important component, because, the higher ECoE is, the less surplus energy remains for those activities which constitute prosperity.

Four main factors drive trends in ECoEs. Taking oil, gas and coal as examples, these energy sources benefited in their early stages from economies of scale and expanding geographic reach. Latterly, though, with these drivers exhausted – and as a consequence of the natural process of using the most attractive sources first, and leaving costlier alternatives for later – ECoEs have been driven upwards relentlessly by depletion.

A fourth factor, technology, accelerates movement along the early, downwards ECoE trajectory, and then acts to mitigate subsequent increases. Mitigation, though, is all that technology can accomplish, because the scope for technological improvement is bounded by the envelope of the physical properties of the energy resource itself.

Lastly on this, because the four factors driving ECoEs – reach, scale, depletion and technology – all act gradually, ECoEs evolve, and need to be measured as trends.

Application – the money complication

With the basic principles established, and the role of ECoE understood, it might seem that, to arrive at a measure of prosperity, all we need do now is to subtract ECoE from economic activity. That would indeed be the case – if we had a reliable data series for output.

But this is something that we simply don’t possess, least of all in reported GDP. Essentially, GDP has been manipulated for the best part of two decades, and, arguably, for even longer than that.

By manipulation, I’m not referring to tinkering at the production boundary, or understating the deflator necessary for making comparisons over time.

The kind of manipulation I have in mind is the simple matter of pillaging the future to inflate perceptions of the present.

Expressed in PPP-converted dollars at constant 2018 values, reported world GDP increased by 36% between 2000 and 2008, and has grown by a further 34% since then. During those same periods, though, world debt increased by, respectively, 50% and 58%. Each $1 of incremental GDP between 2000 and 2008 was accompanied by $2.30 of net new borrowing, a number that has increased to more than $3 in the decade since then. Sustaining annual “growth” of about 3.5% in recent years has required annual borrowing of about 9% of GDP.

In short, GDP and growth have been faked by the simple spending of borrowed money. This exercise in cannibalising the future to sustain the present would look even more extreme were we to include in the equation the creation of huge holes in pension provision.

In this context, we need to answer two questions before we can calculate a useful output metric against which ECoE can be applied.

First, what would happen now, if we stopped piling on yet more debt?

Second, where would GDP be today if we hadn’t embarked on a massive borrowing spree?

You’ll understand, I’m sure – with government, business and finance still hamstrung by the failed economic methodologies of the past – why I won’t go into details here about the SEEDS algorithms which provide answers to these questions.

What I can say, though, is that, in the absence of further net borrowing, growth in world GDP would fall from a reported level of around 3.5%, to about 1.2% now, decreasing to just 0.6% by 2030.

On the second question, setting growth since 2000 of $61tn against borrowing of $167tn over the same period puts in context quite how far reported GDP has been inflated by the spending of borrowed money – and, if this borrowing binge hadn’t happened, GDP now would be 30% below the numbers actually recorded. Instead of “GDP of $135tn PPP, growing at 3.5% annually”, we’d have “GDP of $94tn, growing at barely 1%”.

Prosperity – the ECoE connection

When we set growth in real, “clean” GDP (C-GDP) of 31% since 2000 against a global trend ECoE that has risen from 4.1% to 7.9% over the same period – and stir a 23% increase in population numbers into the pot as well – you’ll readily understand why people have started to become poorer.

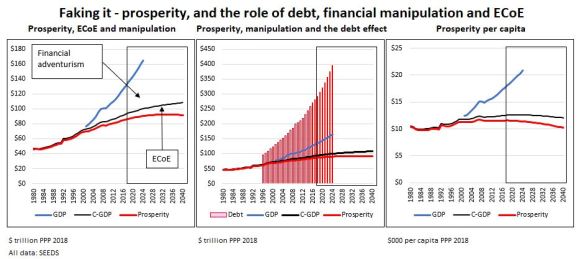

This is set out in fig. 1. In the left-hand chart, the gap between reported GDP (in blue) and C-GDP (black) represents the compound rate of divergence in a period when debt of $167tn has been injected into the system, together with large amounts of ultra-cheap liquidity.

If we were now to unwind these injections, GDP would fall to (or below) the black C-GDP line, over whatever period of time the debt reduction was spread. The gap between C-GDP (black) and prosperity (red) shows the impact of rising ECoEs, and illustrates how the worsening ECoE trend is set to turn low (and faltering) growth in C-GDP into a deteriorating prosperity trend.

The middle chart adds debt, to set these trends in context. In the right-hand chart, per capita equivalents illustrate how the average person has been getting poorer, albeit – so far – pretty gradually.

Fig. 1

Comparing 2000 with 2018 (in constant PPP dollars), a rise of 31% in C-GDP has been offset by an ECoE deduction that has soared from $2.7tn to $7.4tn. Aggregate prosperity has thus increased from $69tn ($71.9tn minus ECoE of $2.7tn) in 2000 to $86tn ($93.5tn minus $7.4tn) last year.

This is a rise of 26%, only slightly greater than the increase (of 23%) in world population numbers between those years. In fact, SEEDS indicates that global prosperity per capita peaked in 2007, at $11,720, and had fallen to $11,570 by last year.

On the cusp of degrowth

This, to be sure, has been a very small decrease, essentially meaning that per capita prosperity has plateaued for slightly more than a decade. Before drawing any comfort at all from this observation, though, the following points need to be noted.

First, the post-2007 plateau contrasts starkly with historic improvements in prosperity. The robust growth of the first two decades after 1945, for instance, coincided with a continuing downwards trend in overall ECoE, as the ECoEs of oil, gas and coal moved towards the lowest points on their respective parabolas.

Second, the deterioration in prosperity, though gradual, has taken place at the same time that debt has escalated. Back in 2007, and expressed at 2018 values, the prosperity of the average person was $11,720, and his or her debt was $27,000. Now, though prosperity is only $140 lower now than it was then, debt has soared to $39,000.

Third, these are aggregated numbers, combining Western economies – where prosperity has been falling over an extended period – with emerging market (EM) countries, where prosperity continues to improve. Once EM economies, too, pass the climacteric into deteriorating prosperity – and that is about to start happening – the global average will fall far more rapidly than the gradual erosion of recent years.

Fourth, as these trends unfold we can expect the rate of deterioration to accelerate, not least because our economic system is predicated on perpetual expansion, and is ill-suited to managing degrowth. In a degrowth phase, in which utilization rates slump and trade volumes fall, increasing numbers of activity-types will cease to be viable (a process that has already commenced). Additionally, of course, we ought to expect the process of degrowth to damage the financial system and this, amongst other adverse effects, will put the “wealth effect” – such as it is – into reverse.

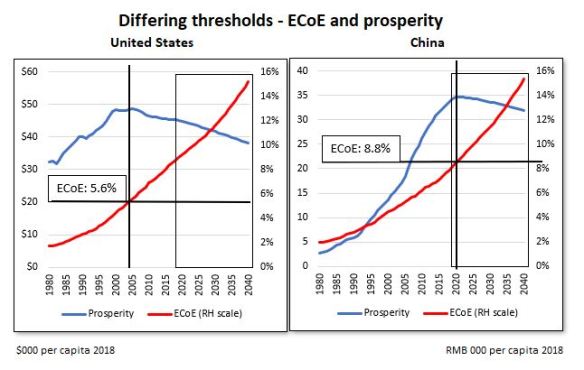

The differences between Western and EM economies is illustrated in fig. 2, which compares the United States with China. On both charts, prosperity per person is shown in blue, and ECoE in red.

In America, prosperity turned down from 2005, when ECoE was 5.6%. In China, on the other hand, SEEDS projects a peaking of prosperity in 2021, by which time ECoE is expected to have reached 8.8%. The reason for this difference is that complex Western economies have far less ECoE-tolerance than less sophisticated EM countries.

As a rule of thumb, prosperity turns downwards in advanced economies at ECoEs of between 3.5% and 5.5%, with the United States far more resilient than weaker Western countries, most notably in Europe. The equivalent band for EM countries seems to lie between 8% and 10%, a threshold that most of these countries are set to cross within the next five or so years.

Where China is concerned, it’s noteworthy that, with ECoE now hitting 8%, there are very evident signs of economic deterioration, including debt dependency, increasing liquidity injections, and falling demand for everything from cars and smartphones to chips and components.

Fig. 2

The energy implications

In conjunction with the SEEDS 20 iteration, the system has adopted a new energy scenario which differs significantly from those set out by institutions such as the U.S. Energy Information Administration and the International Energy Agency.

Essentially, SEEDS broadly agrees with EIA and IEA projections showing increases, between now and 2040, of about 38% for nuclear and 58% for renewables, with the latter defined to include hydroelectricity.

Where SEEDS differs from these institutions is over the outlook for fossil fuels. Using the median expectations of the EIA and the IEA, oil consumption is set to be 11% higher in 2040 than it is now, gas consumption is projected to grow by 32%, and the use of coal is expected to be little changed.

Given the strongly upwards trajectories of the ECoEs of these energy sources, it’s becoming ever harder to see where such increases in supply are supposed to come from. With the US shale liquids sector an established cash-burner, and with most non-OPEC countries now at or beyond their production peaks, it may well be that far too much is being expected of Russia and the Middle East. The oil industry may, in the past, have ‘cried wolf’ over the kind of prices required to finance replacement capacity, but we cannot assume that this is still the case.

The implication for fossil fuels isn’t, necessarily, that worsening scarcity will cause prices to soar but, rather, that it will become increasingly difficult to set prices that are at once both high enough for producers (whose costs are rising) and low enough for consumers (whose prosperity is deteriorating). [MW: see Gail Tverberg on this same exact point.] It’s becoming an increasingly plausible scenario that the supply of oil, gas and coal may cease to be activities suited to for-profit private operators, and that some form of direct subsidy may become inescapable.

Conclusions

It is to be hoped that this discussion has persuaded you of two things – the abject failure of ‘conventional’, money-based economics, and the imperative need to adopt interpretations based on a recognition of the (surely obvious) fact that the economy is an energy system.

Until and unless this happens, we’re going to carry on telling ourselves pretty lies about prosperity, and acting in ways characterised by an increasingly desperate impulse towards denial. Many governments are already taxing their citizens to an extent that, whilst it might seem reasonable in the context of overstated GDP, causes real hardship and discontent when set against the steady deterioration of prosperity.

Meanwhile, risk, as measured financially, keeps rising, and the cumulative gap between assumed GDP and underlying prosperity has reached epic proportions. Expressed in market (rather than PPP) dollars, scope for value destruction has now reached $320tn.

Only part of this is likely to take the form of debt defaults, though these could take on a compounding, domino-like progression. Just as seriously, asset valuations look set to tumble, when we are forced to realise that unleashing tides of cheap debt and cheaper money provides no genuine “fix” to an economy in degrowth, but serves only to compound the illusions on which economic assumptions and decisions are based.

No comments:

Post a Comment