There is no doubt that racism is a continuing problem.

There is no doubt that there are racist cops.

There is no doubt that black Americans have been victims of police brutality.

There is no doubt that white Americans have been victims of police brutality.

There is no doubt that there are psychopathic cops.

There is no doubt that psychopathy in American policing is a continuing problem.

Liberal Media Bias

Manipulative Media

Police Brutality and Black-on-Black Crime

What the data say about police shootings. Lynne Peeples, Nature. Sept. 4, 2019.

How do racial biases play into deadly encounters with the police? Researchers wrestle with incomplete data to reach answers.

On Tuesday 6 August, the police shot and killed a schoolteacher outside his home in Shaler Township, Pennsylvania. He had reportedly pointed a gun at the officers. In Grants Pass, Oregon, that same day, a 39-year-old man was shot and killed after an altercation with police in the state police office. And in Henderson, Nevada, that evening, an officer shot and injured a 15-year-old suspected of robbing a convenience store. The boy reportedly had an object in his hand that the police later confirmed was not a deadly weapon.

In the United States, police officers fatally shoot about three people per day on average, a number that’s close to the yearly totals for other wealthy nations. But data on these deadly encounters have been hard to come by.

A pair of high-profile killings of unarmed black men by the police pushed this reality into the headlines in summer 2014. Waves of public protests broke out after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the death by chokehold of Eric Garner in New York City.

Those cases and others raised questions about the extent to which racial biases — either implicit associations or outright racism — contribute to the use of lethal force by the police across the United States. And yet there was no source of comprehensive information to investigate the issue. Five years later, newspapers, enterprising individuals and the federal government have launched ambitious data-collection projects to fill the gaps and improve transparency and accountability over how police officers exercise their right to use deadly force.

“It is this awesome power that they have that no other profession has,” says Justin Nix, a criminologist at the University of Nebraska Omaha. “Let’s keep track of it.”

Social scientists and public-health researchers have begun to dig into these records and have produced more than 50 publications so far — up from a trickle of papers on the topic before 2015. They are mining the new numbers to address pressing questions, such as whether the police are disproportionately quick to shoot black civilians and those from other minority groups. But methods and interpretations vary greatly. A pair of high-profile papers published in the past few weeks1,2 come to seemingly opposite conclusions about the role of racial biases.

Scientists are now debating which incidents to track — from deadly shootings to all interactions with the public — and which details matter most, such as whether the victim was armed or had had previous contact with the police. They are also looking for the best way to compare activities across jurisdictions and account for misreporting. “It’s really contentious because there’s no clearly right answer,” says Seth Stoughton at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, a former police officer who now studies the regulation of law enforcement.

Although the databases are still imperfect, they make it clear that police officers’ use of lethal force is much more common than previously thought, and that it varies significantly across the country, including the two locations where Brown and Garner lost their lives. St Louis (of which Ferguson is a suburb) has one of the highest rates of police shooting civilians per capita in the United States, whereas New York City consistently has one of the lowest, according to one database. Deciphering what practices and policies drive such differences could identify opportunities to reduce the number of shootings and deaths for both civilians and police officers, scientists say.

“We need to standardize definitions and start counting,” says Stoughton. “As the old saying goes, ‘What gets measured, gets managed.’”

Spotlight on a blind spot

In December 2014, spurred by unrest in the wake of Ferguson, then-US president, Barack Obama, created a task force to investigate policing practices. The group issued a report five months later, highlighting a need for “expanded research and data collection” (see go.nature.com/2kqoddk). The data historically collected by the federal government on fatal shootings were sorely lacking. Almost two years later, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) responded with a pilot project to create an online national database of fatal and non-fatal use of force by law-enforcement officers. The FBI director at the time, James Comey, called the lack of comprehensive national data “unacceptable” and “embarrassing”.

Full data collection started this year. But outsiders had already begun to gather the data in the interests of informing the public. The database considered to be the most complete is maintained by The Washington Post. In 2015, the newspaper began collecting information on fatal shootings from local news reports, public records and social media. Its records indicate that police officers shoot and kill around 1,000 civilians each year — about twice the number previously counted by the FBI.

Recognizing that ‘lethal force’ does not always involve a gun and doesn’t always result in death, two other media organizations expanded on this approach. In 2015 and 2016, UK newspaper The Guardian combined its original reporting with crowdsourced information to record all fatal encounters with the police in the United States, and found around 1,100 civilian deaths per year. Online news site VICE News obtained data on both fatal and non-fatal shootings from the country’s 50 largest local police departments, finding that for every person shot and killed between 2010 and 2016, officers shot at two more people who survived. Extrapolating from that, the actual number of civilians shot by the police each year is likely to be upwards of 3,000.

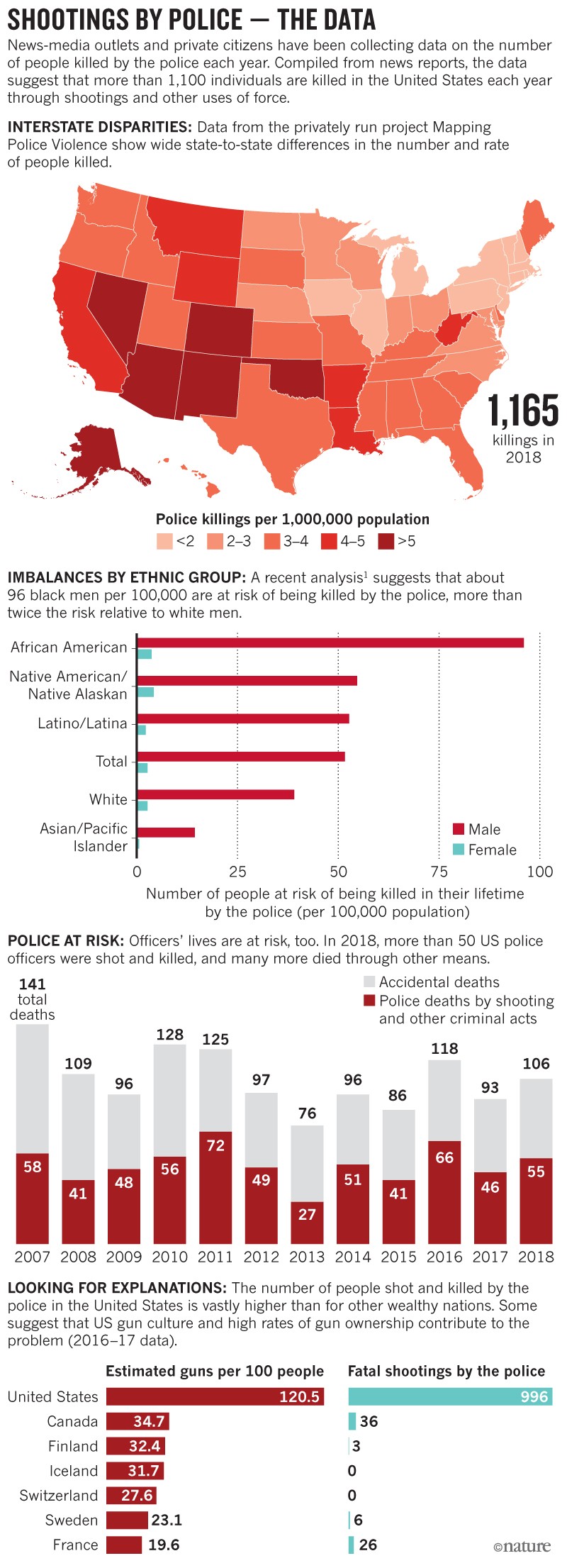

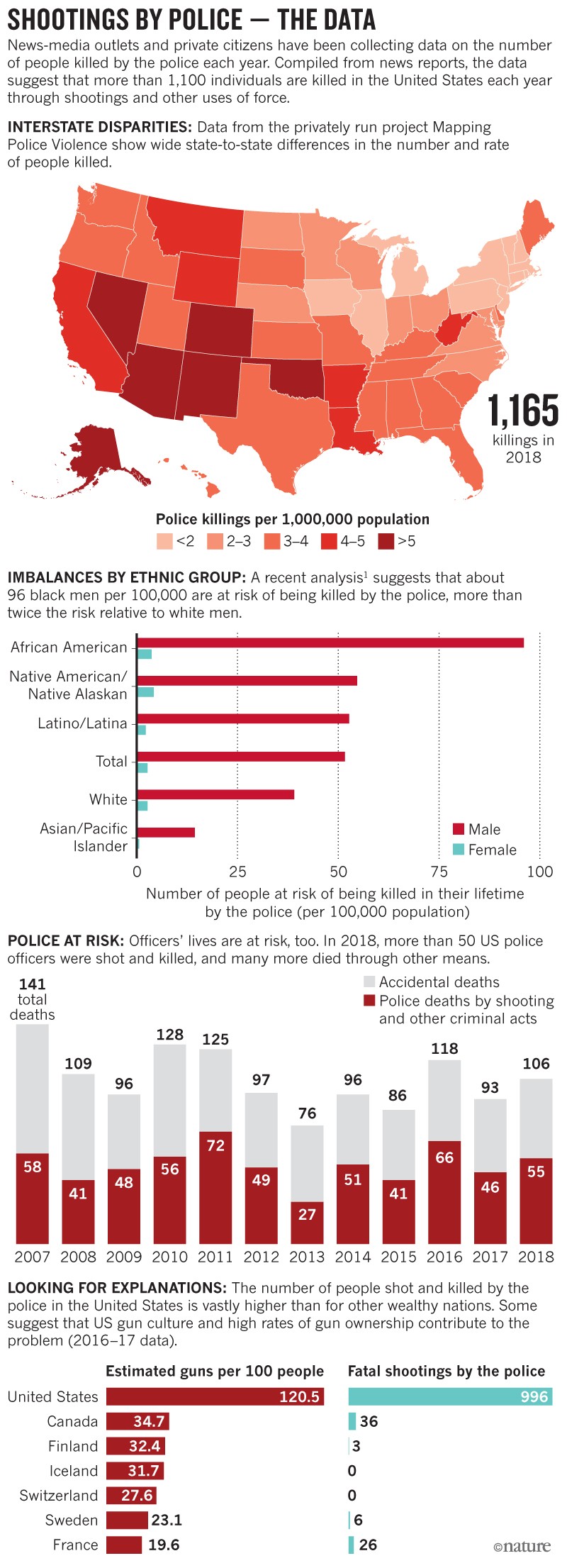

Unofficial national databases have also popped up outside the major news organizations. Two small-scale private efforts, Fatal Encounters and Mapping Police Violence, aggregate and verify information from other databases with added details gleaned from social media, obituaries, criminal-records databases and police reports (see ‘Shootings by police — the data’).

Sources: Map: Mapping Police Violence; Ethnic imbalance: ref. 1; Police deaths: FBI LEOKA report 2018

The results paint a picture of definite disparity when it comes to race and police shootings. Although more white people are shot in total, people from minority ethnic groups are shot at higher rates by population. One paper published in August found that a black man is 2.5 times more likely than a white man to be killed by the police during his lifetime1. The difference, albeit smaller, is also there for women. But the authors did not make any conclusions regarding racial bias of police officers, in part because not everyone has an equal chance of coming into contact with the police. Crime rates and policing practices differ across communities, as do the historical legacies that influence them. Aggressive policing over time can increase local levels of violence and contact with the police, says Frank Edwards, a sociologist at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, and an author on the paper. “This is inherently a multilevel problem,” he says.

Researchers have used various approaches to try to determine the best benchmarks for the data, such as looking at the arrest rates where the shootings occurred or factoring in the context of encounters that end in a shooting. Did the suspect have a weapon? Were officers or another civilian being threatened? In a 2017 study3, for example, Nix determined that black people fatally shot by the police were twice as likely as white people to be unarmed. Those findings align with many studies published since 2015 suggesting that racial biases do influence police shootings.

Some research runs counter to this conclusion. This July, authors of a study that pulled information from The Washington Post and The Guardian databases, as well as directly from police departments, said they found no evidence of biases against black or Hispanic people2. In addition to factoring in the crime rates of the communities where the shootings happened, the authors looked at the race of the officers involved.

Several scientists have taken issue with their methods, however. To sidestep some of the questions about encounter rates, the study authors started from the pool of people shot by the police and then calculated the chance that they were of a certain race. Jonathan Mummolo, a political scientist at Princeton University, New Jersey, argues that the real question to ask in order to detect racial bias is the reverse: does a citizen of a certain race face a greater chance of getting shot by the police? And answering this question requires knowing, or at least reasonably approximating, that elusive encounter rate.

The national-scale databases are inherently messy, in part as a result of disparate definitions of the ‘use of force’, as well as different police protocols and reporting requirements. Other studies have avoided some of these inconsistencies by focusing on local data.

A 2017 study of data collected from the Dallas Police Department in Texas indicated that although race was not a significant factor in decisions to pull the trigger, Dallas officers were more likely to draw their firearms on minority suspects4.

The Dallas Police Department declined to comment on the study but highlighted its officer-education efforts, including in areas of cultural diversity and implicit bias, as well as its deployment of body cameras, which many agencies have adopted as a way to improve transparency.

Some researchers say it’s important to shift the discussion to examine when — rather than whether — racial bias factors into the use of deadly force. Does it come into play when a department decides which neighbourhoods to police most heavily? Or is it when an officer first lays eyes on a civilian, or is it when they make that split-second decision to pull the trigger? Andrew Wheeler, a criminologist at the University of Texas at Dallas, says that national-level databases should at least include all levels of use of force — down to the drawing of a weapon — in order to answer questions and create change. “Collecting data in and of itself is a good mechanism to hold police agencies accountable,” he says.

Counting on the Feds

In January, after more than three years of pilot development, the FBI unveiled its official National Use-of-Force Data Collection, which covers dozens of variables including fatal and non-fatal injuries incurred through a variety of police encounters. The database, according to the FBI, aims to inform dialogue by filling the information gap. But data submission is entirely voluntary. And no data are yet available for outside review.

Nix and others doubt that all of the more than 18,000 police agencies in the United States will voluntarily report incidents. But Darrel Stephens, a retired police chief and the interim executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Association, is more optimistic. Growing public pressure will force agencies to participate, he says. At the same time, he adds, the increased scrutiny since Ferguson has also come at a cost. In a 2017 national survey by the Pew Research Center, 76% of police officers reported that they had become more reluctant to use force when it is appropriate. Police officers, too, face risks. An average of around 50 officers are shot and killed by civilians every year.

In other wealthy nations, where accurate tracking of shootings is generally a given, officials tend to have fewer deaths of both civilians and officers to count. Terry Goldsworthy, a criminologist at Bond University in Queensland, Australia, highlights one potential explanation for the difference: a stark contrast in the attitude towards and availability of guns. “Generally, when a police officer pulls up to a car in Australia, they don’t expect someone to be armed,” he says.

Australia keeps a tally of its approximately five civilian deaths at the hands of the police per year, using a central government database. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, an independent inquiry is initiated every time a police officer is involved in a shooting.

To encourage US law-enforcement agencies to report use-of-force information, Stoughton, who has published widely on deadly force, says officials should consider making federal grants conditional on whether departments submit use-of-force data to national collections. But he recognizes the challenges. “We’re not talking about anything that is practically difficult,” he says. “This is something that is politically difficult.”

Researchers, meanwhile, aren’t going to wait around for the FBI. Some are refining methods to better analyse the imperfect data they have; others are continually trying to improve the information collected so far. Academics are expanding the Fatal Encounters database and filling in holes, for example, by adding police-department demographics and the location of the nearest emergency department, as well as using surname and demographic information to guess at the race of someone where it isn’t identified. “I don’t think we’ve closed the book on any of this,” says Mummolo. “We’re just beginning.”

Is 'Reverse Racism' Among Police Real? Brentin Mock. Feb. 8, 2017.

The Truth Behind Racial Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings. Joseph Cesario, MSU. July 22, 2019.

The Myth of Systemic Police Racism. Heather MacDonald. WSJ. June 2, 2020.

Hold officers accountable who use excessive force. But there’s no evidence of widespread racial bias.

The George Floyd Protests – 20 unanswered questions

As the situation deterioates all across the nation, we need to stop and ask how we got here

The Minneapolis Putsch. CJ Hopkins. The Off-Guardian. June 1, 2020.

Seven Reasons Why Police Are Disliked. Randall Collins, The Sociological Eye. June 5, 2020.

Number of people shot to death by the police in the United States from 2017 to 2020, by race. Statista.

Rush to Judgment. Norman Mailer. 1966.

There is no doubt that there are racist cops.

There is no doubt that black Americans have been victims of police brutality.

There is no doubt that white Americans have been victims of police brutality.

There is no doubt that there are psychopathic cops.

There is no doubt that psychopathy in American policing is a continuing problem.

Liberal Media Bias

Manipulative Media

Police Brutality and Black-on-Black Crime

What the data say about police shootings. Lynne Peeples, Nature. Sept. 4, 2019.

How do racial biases play into deadly encounters with the police? Researchers wrestle with incomplete data to reach answers.

On Tuesday 6 August, the police shot and killed a schoolteacher outside his home in Shaler Township, Pennsylvania. He had reportedly pointed a gun at the officers. In Grants Pass, Oregon, that same day, a 39-year-old man was shot and killed after an altercation with police in the state police office. And in Henderson, Nevada, that evening, an officer shot and injured a 15-year-old suspected of robbing a convenience store. The boy reportedly had an object in his hand that the police later confirmed was not a deadly weapon.

In the United States, police officers fatally shoot about three people per day on average, a number that’s close to the yearly totals for other wealthy nations. But data on these deadly encounters have been hard to come by.

A pair of high-profile killings of unarmed black men by the police pushed this reality into the headlines in summer 2014. Waves of public protests broke out after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the death by chokehold of Eric Garner in New York City.

Those cases and others raised questions about the extent to which racial biases — either implicit associations or outright racism — contribute to the use of lethal force by the police across the United States. And yet there was no source of comprehensive information to investigate the issue. Five years later, newspapers, enterprising individuals and the federal government have launched ambitious data-collection projects to fill the gaps and improve transparency and accountability over how police officers exercise their right to use deadly force.

“It is this awesome power that they have that no other profession has,” says Justin Nix, a criminologist at the University of Nebraska Omaha. “Let’s keep track of it.”

Social scientists and public-health researchers have begun to dig into these records and have produced more than 50 publications so far — up from a trickle of papers on the topic before 2015. They are mining the new numbers to address pressing questions, such as whether the police are disproportionately quick to shoot black civilians and those from other minority groups. But methods and interpretations vary greatly. A pair of high-profile papers published in the past few weeks1,2 come to seemingly opposite conclusions about the role of racial biases.

Scientists are now debating which incidents to track — from deadly shootings to all interactions with the public — and which details matter most, such as whether the victim was armed or had had previous contact with the police. They are also looking for the best way to compare activities across jurisdictions and account for misreporting. “It’s really contentious because there’s no clearly right answer,” says Seth Stoughton at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, a former police officer who now studies the regulation of law enforcement.

Although the databases are still imperfect, they make it clear that police officers’ use of lethal force is much more common than previously thought, and that it varies significantly across the country, including the two locations where Brown and Garner lost their lives. St Louis (of which Ferguson is a suburb) has one of the highest rates of police shooting civilians per capita in the United States, whereas New York City consistently has one of the lowest, according to one database. Deciphering what practices and policies drive such differences could identify opportunities to reduce the number of shootings and deaths for both civilians and police officers, scientists say.

“We need to standardize definitions and start counting,” says Stoughton. “As the old saying goes, ‘What gets measured, gets managed.’”

Spotlight on a blind spot

In December 2014, spurred by unrest in the wake of Ferguson, then-US president, Barack Obama, created a task force to investigate policing practices. The group issued a report five months later, highlighting a need for “expanded research and data collection” (see go.nature.com/2kqoddk). The data historically collected by the federal government on fatal shootings were sorely lacking. Almost two years later, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) responded with a pilot project to create an online national database of fatal and non-fatal use of force by law-enforcement officers. The FBI director at the time, James Comey, called the lack of comprehensive national data “unacceptable” and “embarrassing”.

Full data collection started this year. But outsiders had already begun to gather the data in the interests of informing the public. The database considered to be the most complete is maintained by The Washington Post. In 2015, the newspaper began collecting information on fatal shootings from local news reports, public records and social media. Its records indicate that police officers shoot and kill around 1,000 civilians each year — about twice the number previously counted by the FBI.

Recognizing that ‘lethal force’ does not always involve a gun and doesn’t always result in death, two other media organizations expanded on this approach. In 2015 and 2016, UK newspaper The Guardian combined its original reporting with crowdsourced information to record all fatal encounters with the police in the United States, and found around 1,100 civilian deaths per year. Online news site VICE News obtained data on both fatal and non-fatal shootings from the country’s 50 largest local police departments, finding that for every person shot and killed between 2010 and 2016, officers shot at two more people who survived. Extrapolating from that, the actual number of civilians shot by the police each year is likely to be upwards of 3,000.

Unofficial national databases have also popped up outside the major news organizations. Two small-scale private efforts, Fatal Encounters and Mapping Police Violence, aggregate and verify information from other databases with added details gleaned from social media, obituaries, criminal-records databases and police reports (see ‘Shootings by police — the data’).

Sources: Map: Mapping Police Violence; Ethnic imbalance: ref. 1; Police deaths: FBI LEOKA report 2018

The results paint a picture of definite disparity when it comes to race and police shootings. Although more white people are shot in total, people from minority ethnic groups are shot at higher rates by population. One paper published in August found that a black man is 2.5 times more likely than a white man to be killed by the police during his lifetime1. The difference, albeit smaller, is also there for women. But the authors did not make any conclusions regarding racial bias of police officers, in part because not everyone has an equal chance of coming into contact with the police. Crime rates and policing practices differ across communities, as do the historical legacies that influence them. Aggressive policing over time can increase local levels of violence and contact with the police, says Frank Edwards, a sociologist at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, and an author on the paper. “This is inherently a multilevel problem,” he says.

Researchers have used various approaches to try to determine the best benchmarks for the data, such as looking at the arrest rates where the shootings occurred or factoring in the context of encounters that end in a shooting. Did the suspect have a weapon? Were officers or another civilian being threatened? In a 2017 study3, for example, Nix determined that black people fatally shot by the police were twice as likely as white people to be unarmed. Those findings align with many studies published since 2015 suggesting that racial biases do influence police shootings.

Some research runs counter to this conclusion. This July, authors of a study that pulled information from The Washington Post and The Guardian databases, as well as directly from police departments, said they found no evidence of biases against black or Hispanic people2. In addition to factoring in the crime rates of the communities where the shootings happened, the authors looked at the race of the officers involved.

Several scientists have taken issue with their methods, however. To sidestep some of the questions about encounter rates, the study authors started from the pool of people shot by the police and then calculated the chance that they were of a certain race. Jonathan Mummolo, a political scientist at Princeton University, New Jersey, argues that the real question to ask in order to detect racial bias is the reverse: does a citizen of a certain race face a greater chance of getting shot by the police? And answering this question requires knowing, or at least reasonably approximating, that elusive encounter rate.

The national-scale databases are inherently messy, in part as a result of disparate definitions of the ‘use of force’, as well as different police protocols and reporting requirements. Other studies have avoided some of these inconsistencies by focusing on local data.

A 2017 study of data collected from the Dallas Police Department in Texas indicated that although race was not a significant factor in decisions to pull the trigger, Dallas officers were more likely to draw their firearms on minority suspects4.

The Dallas Police Department declined to comment on the study but highlighted its officer-education efforts, including in areas of cultural diversity and implicit bias, as well as its deployment of body cameras, which many agencies have adopted as a way to improve transparency.

Some researchers say it’s important to shift the discussion to examine when — rather than whether — racial bias factors into the use of deadly force. Does it come into play when a department decides which neighbourhoods to police most heavily? Or is it when an officer first lays eyes on a civilian, or is it when they make that split-second decision to pull the trigger? Andrew Wheeler, a criminologist at the University of Texas at Dallas, says that national-level databases should at least include all levels of use of force — down to the drawing of a weapon — in order to answer questions and create change. “Collecting data in and of itself is a good mechanism to hold police agencies accountable,” he says.

Counting on the Feds

In January, after more than three years of pilot development, the FBI unveiled its official National Use-of-Force Data Collection, which covers dozens of variables including fatal and non-fatal injuries incurred through a variety of police encounters. The database, according to the FBI, aims to inform dialogue by filling the information gap. But data submission is entirely voluntary. And no data are yet available for outside review.

Nix and others doubt that all of the more than 18,000 police agencies in the United States will voluntarily report incidents. But Darrel Stephens, a retired police chief and the interim executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Association, is more optimistic. Growing public pressure will force agencies to participate, he says. At the same time, he adds, the increased scrutiny since Ferguson has also come at a cost. In a 2017 national survey by the Pew Research Center, 76% of police officers reported that they had become more reluctant to use force when it is appropriate. Police officers, too, face risks. An average of around 50 officers are shot and killed by civilians every year.

In other wealthy nations, where accurate tracking of shootings is generally a given, officials tend to have fewer deaths of both civilians and officers to count. Terry Goldsworthy, a criminologist at Bond University in Queensland, Australia, highlights one potential explanation for the difference: a stark contrast in the attitude towards and availability of guns. “Generally, when a police officer pulls up to a car in Australia, they don’t expect someone to be armed,” he says.

Australia keeps a tally of its approximately five civilian deaths at the hands of the police per year, using a central government database. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, an independent inquiry is initiated every time a police officer is involved in a shooting.

To encourage US law-enforcement agencies to report use-of-force information, Stoughton, who has published widely on deadly force, says officials should consider making federal grants conditional on whether departments submit use-of-force data to national collections. But he recognizes the challenges. “We’re not talking about anything that is practically difficult,” he says. “This is something that is politically difficult.”

Researchers, meanwhile, aren’t going to wait around for the FBI. Some are refining methods to better analyse the imperfect data they have; others are continually trying to improve the information collected so far. Academics are expanding the Fatal Encounters database and filling in holes, for example, by adding police-department demographics and the location of the nearest emergency department, as well as using surname and demographic information to guess at the race of someone where it isn’t identified. “I don’t think we’ve closed the book on any of this,” says Mummolo. “We’re just beginning.”

Is 'Reverse Racism' Among Police Real? Brentin Mock. Feb. 8, 2017.

Criminologists have debated for decades whether police carry racial biases into their work—particularly the kind that leads them to kill African Americans at disproportionate rates. Much of the research in this arena suggests that yes, on balance, police officers of all races do tend to perceive African Americans as more threatening than whites. The much-revered University of California Berkeley criminology professor Paul Takagi wrote as early as 1974 that “the police have one trigger finger for whites and another for blacks,” in the Journal of Crime and Scholarly Justice.

However, a few recent studies upended the conventional wisdom on this by pointing to evidence that police might be more hesitant to use deadly force against black suspects, as opposed to white suspects. Such studies leveled up the stakes around the so-called “Ferguson Effect”: Not only were cops scaling back their policing to avoid potential public scrutiny, as this effect supposes, but they’re now being more racist towards white people, these new studies allege.

The sheer volume of news stories over the last few years showing police using force against African Americans—both armed and unarmed—certainly suggest otherwise. After all, those stories are what propelled the Black Lives Matter movement, which continues to push for more awareness about police violence. Those stories also prompted a group of researchers to dig a little deeper into the question of whether police are biased against minorities. In a report released today, “A Bird’s Eye View of Civilians Killed by Police in 2015,” criminal justice scholars from the University of Louisville and the University of South Carolina found an interesting way to ascertain how racial discrimination might play a role in police violence.

...

Another study, conducted by Harvard sociologist Roland Fryer last year, had similar findings. After examining over 1,300 police shootings in some of the nation’s largest cities, he found no evidence that police were more likely to shoot black suspects over whites. Wrote Fryer in the conclusion to his report: “It is plausible that racial differences in lower level uses of force are simply a distraction and movements such as Black Lives Matter should seek solutions within their own communities rather than changing the behaviors of police and other external forces.”

The Truth Behind Racial Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings. Joseph Cesario, MSU. July 22, 2019.

“Until now, there’s never been a systematic, nationwide study to determine the characteristics of police involved in fatal officer-involved shootings,” said Joseph Cesario, co-author and professor of psychology at MSU. “There are so many examples of people saying that when black citizens are shot by police, it’s white officers shooting them. In fact, our findings show no support that black citizens are more likely to be shot by white officers."

“We found that the race of the officer doesn’t matter when it comes to predicting whether black or white citizens are shot," Cesario said. "If anything, black citizens are more likely to have been shot by black officers, but this is because black officers are drawn from the same population that they police. So, the more black citizens there are in a community, the more black police officers there are.”

... “Many people ask whether black or white citizens are more likely to be shot and why. We found that violent crime rates are the driving force behind fatal shootings,” Cesario said. “Our data show that the rate of crime by each racial group correlates with the likelihood of citizens from that racial group being shot. If you live in a county that has a lot of white people committing crimes, white people are more likely to be shot. If you live in a county that has a lot of black people committing crimes, black people are more likely to be shot. It is the best predictor we have of fatal police shootings.”

... There’s also something to be said for what the victims were doing when the cops shot them. Cesario points out that, “The vast majority—between 90 percent and 95 percent—of the civilians shot by officers were actively attacking police or other citizens when they were shot”—and that there were more white civilians who were committing such attacks when police killed them than were African Americans. In fact, white people were more likely to be armed when police killed them, as Cesario’s study acknowledges—“if anything, [we] found anti-White disparities when controlling for race-specific crime,” reads the study.

The Myth of Systemic Police Racism. Heather MacDonald. WSJ. June 2, 2020.

Hold officers accountable who use excessive force. But there’s no evidence of widespread racial bias.

The charge of systemic police bias was wrong during the Obama years and remains so today. However sickening the video of Floyd’s arrest, it isn’t representative of the 375 million annual contacts that police officers have with civilians. A solid body of evidence finds no structural bias in the criminal-justice system with regard to arrests, prosecution or sentencing. Crime and suspect behavior, not race, determine most police actions.

In 2019 police officers fatally shot 1,004 people, most of whom were armed or otherwise dangerous. African-Americans were about a quarter of those killed by cops last year (235), a ratio that has remained stable since 2015. That share of black victims is less than what the black crime rate would predict, since police shootings are a function of how often officers encounter armed and violent suspects. In 2018, the latest year for which such data have been published, African-Americans made up 53% of known homicide offenders in the U.S. and commit about 60% of robberies, though they are 13% of the population.

The police fatally shot nine unarmed blacks and 19 unarmed whites in 2019, according to a Washington Post database, down from 38 and 32, respectively, in 2015.

...

This past weekend, 80 Chicagoans were shot in drive-by shootings, 21 fatally, the victims overwhelmingly black. Police shootings are not the reason that blacks die of homicide at eight times the rate of whites and Hispanics combined; criminal violence is.

Twigs on the same branch? Identifying personality profiles in police officers using psychopathic personality traits. Diana M. Falkenbach et al. Journal of Research in Personality. Oct. 2018.

Abstract

Recent high-profile incidents reignited the conversation about psychopathic traits in police officers. Psychopathy is characterized by multiple variants: primary and secondary psychopathy. There is limited research examining psychopathy in populations that may exhibit adaptive psychopathic traits. This study used model-based cluster analyses of high psychopathy scorers to investigate psychopathic subtypes in an urban police sample. Relative to the primary subtype, the secondary group displayed higher levels of Self-Centered Impulsivity, trait anxiety, covert narcissism, borderline personality disorder traits, substance use, psychiatric treatment, and aggression. These findings support the concept of successful psychopathy and the existence of psychopathy profiles in police officers, providing a useful look at how successful psychopathy may manifest as well as implications for the criminal justice system and police departments.

Psychopathic cops can be more dangerous than criminals. They are responsible for police brutality, unjustified shootings, false testimony, and many other forms of police misconduct.

Every year, dozens of people who were convicted based on a cop's testimony, are released from prison because they were innocent. In three out of four homicide exonerations, official misconduct is a factor.

Thousands of Americans have died at the hands of cops in suspicious circumstances. This kind of behaviors are, more often than not, the work of a psychopath.

What is a Psychopath?

One of the problems with psychopaths is that they are incapable of remorse.

For Jon Ronson, author of The Psychopath Test, “Psychopathy is probably the most pleasant-feeling of all the mental disorders... All of the things that keep you good, morally good, are painful things: guilt, remorse, empathy.” For neuroscientist James Fallon, author of The Psychopath Inside, “Psychopaths can work very quickly, and can have an apparent IQ higher than it really is, because they’re not inhibited by moral concerns.”

Psychopaths have cognitive empathy, they can understand what others are feeling, but they lack the ability to feel it, which is known as emotional empathy. “This all gives certain psychopaths a great advantage, because they can understand what you’re thinking, it’s just that they don’t care, so they can use you against yourself,” Fallon explains.

In fact, research has shown that psychopaths are extremely adept at identifying vulnerability.

Psychopaths Often Become Cops

What happens when a person like that, someone who has zero concern for our feelings, is handed a gun and put in a position of power?

An encounter with a psychopath in a police uniform can be a life hazard. That's why it is so important to be able to detect them. When you are in front of a psychopath, behaviors need to be altered, because normal social behaviors can trigger unexpected responses.

Research has shown that Police Officer is one of the top 10 professions chosen by psychopaths, ranking at number 7.

As I wrote in my book - California: State of Collusion, “Power, such as we give to law enforcement, prosecutors and judges, actually attracts psychopathic personalities who want to exert violent dominance under the color of authority. Innocent people can be subjected to a power trip police encounter, can be arrested by a megalomaniacal cop, jailed by a sadist, prosecuted by a manipulative Machiavellian and judged by a sociopath on an ego trip.”

The George Floyd Protests – 20 unanswered questions

As the situation deterioates all across the nation, we need to stop and ask how we got here

Violence, looting and riots won’t solve any of the political problems in America, but will cause more. So why are they being encouraged?

As this gets published, curfews are being introduced all across the country, national guard units are on high alert, and the media continue to pump out alarmist stories stoking the conflict.

Who will benefit from this chaos?

The Minneapolis Putsch. CJ Hopkins. The Off-Guardian. June 1, 2020.

Things couldn’t be going better for the Resistance if they had scripted it themselves.

Actually, they did kind of script it themselves. Not the murder of poor George Floyd, of course. Racist police have been murdering Black people for as long as there have been racist police. No, the Resistance didn’t manufacture racism.

They just spent the majority of the last four years creating and promoting an official narrative which casts most Americans as “white supremacists” who literally elected Hitler president, and who want to turn the country into a racist dictatorship.

According to this official narrative, which has been relentlessly disseminated by the corporate media, the neoliberal intelligentsia, the culture industry, and countless hysterical, Trump-hating loonies, the Russians put Donald Trump in office with those DNC emails they never hacked and some division-sowing Facebook ads that supposedly hypnotized Black Americans into refusing to come out and vote for Clinton. Putin purportedly ordered this personally, as part of his plot to “destroy democracy.”

The plan was always for President Hitler to embolden his white-supremacist followers into launching the “RaHoWa,” or the “Boogaloo,” after which Trump would declare martial law, dissolve the legislature, and pronounce himself Führer. Then they would start rounding up and murdering the Jews, and the Blacks, and Mexicans, and other minorities, according to this twisted liberal fantasy.

I’ve been covering the roll-out and dissemination of this official narrative since 2016, and have documented much of it in my essays, so I won’t reiterate all that here. Let’s just say, I’m not exaggerating, much.

After four years of more or less constant conditioning, millions of Americans believe this fairy tale, despite the fact that there is absolutely zero evidence whatsoever to support it. Which is not exactly a mystery or anything. It would be rather surprising if they didn’t believe it. We’re talking about the most formidable official propaganda machine in the history of official propaganda machines.

And now the propaganda is paying off. The protesting and rioting that typically follows the murder of an unarmed Black person by the cops has mushroomed into “an international uprising” cheered on by the corporate media, corporations, and the liberal establishment, who don’t normally tend to support such uprisings, but they’ve all had a sudden change of heart, or spiritual or political awakening, and are down for some serious property damage, and looting, and preventative self-defense, if that’s what it takes to bring about justice, and to restore America to the peaceful, prosperous, non-white-supremacist paradise it was until the Russians put Donald Trump in office.

In any event, the Resistance media have now dropped their breathless coverage of the non-existent Corona-Holocaust to breathlessly cover the “revolution.”

...

Look, I’m not saying the neoliberal Resistance orchestrated or staged these riots, or “denying the agency” of the folks in the streets. Whatever else is happening out there, a lot of very angry Black people are taking their frustration out on the cops, and on anyone and anything else that represents racism and injustice to them.

This happens in America from time to time. America is still a racist society. Most African-Americans are descended from slaves. Legal racial discrimination was not abolished until the 1960s, which isn’t that long ago in historical terms.

...

So I have no illusions about racism in America. But I’m not really talking about racism in America. I’m talking about how racism in America has been cynically instrumentalized, not by the Russians, but by the so-called Resistance, in order to delegitimize Trump and, more importantly, everyone who voted for him, as a bunch of white supremacists and racists.

...

OK, and this is where I have to restate (for the benefit of my partisan readers) that I’m not a fan of Donald Trump, and that I think he’s a narcissistic ass clown, and a glorified con man, and … blah blah blah, because so many people have been so polarized by insane propaganda and mass hysteria that they can’t even read or think anymore, and so just scan whatever articles they encounter to see whose “side” the author is on and then mindlessly celebrate or excoriate it.

If you’re doing that, let me help you out … whichever side you’re on, I’m not on it.

I realize that’s extremely difficult for a lot of folks to comprehend these days, which is part of the point I’ve been trying to make. I’ll try again, as plainly as I can.

America is still a racist country, but America is no more racist today than it was when Barack Obama was president. A lot of American police are brutal, but no more brutal than when Obama was president. America didn’t radically change the day Donald Trump was sworn into office.

All that has changed is the official narrative. And it will change back as soon as Trump is gone and the ruling classes have no further use for it.

And that will be the end of the War on Populism, and we will switch back to the War on Terror, or maybe the Brave New Pathologized Normal … or whatever Orwellian official narrative the folks at GloboCap have in store for us.

Seven Reasons Why Police Are Disliked. Randall Collins, The Sociological Eye. June 5, 2020.

[7] Racism among police. Some cops are racists. How many are there, and what kind of racists they are, needs better analysis. What kind? There is a difference between white supremacists of the pre-1960s period; stereotyping racists who think most black people are potential criminals; situational racists who react to black people in confrontational situations with fear and hostility; casual racists who make jokes. These aren’t insoluble questions; if ethnographers followed people around in everyday life and observed what they talked about and how they behaved in different situations, we would have a good picture. And there still remains the further question, does one or another degree of racism explain when police violence happens?

My estimate is that racism among police is less important a factor than the social conflicts and situational stresses outlined in points [1-6]. To put it another way, if we got rid of racist attitudes, but left [1-6] in place, how much would police violence be reduced? Very little, I would predict.

What can be done? And how likely is it to have effects? ...

Rush to Judgment. Norman Mailer. 1966.

No comments:

Post a Comment