The Hump. Conway, The Material World. Dec 22, 2023.

Quite early on in Material World I wrote that :

pursuing our various environmental goals will, in the short and medium term, require considerably more materials to build the electric cars, wind turbines and solar panels needed to replace fossil fuels. The upshot is that in the coming decades we are likely to extract more metals from the earth’s surface than ever before.

The point being that while in the long run it’s quite possible that we reduce the size of humanity’s footprint on the planet, in the immediate future we will do a lot more exploiting. We will mine more, refine more and consume more stuff - and the stuff we need for the energy transition will only add to this material intensity. The footprint will grow.

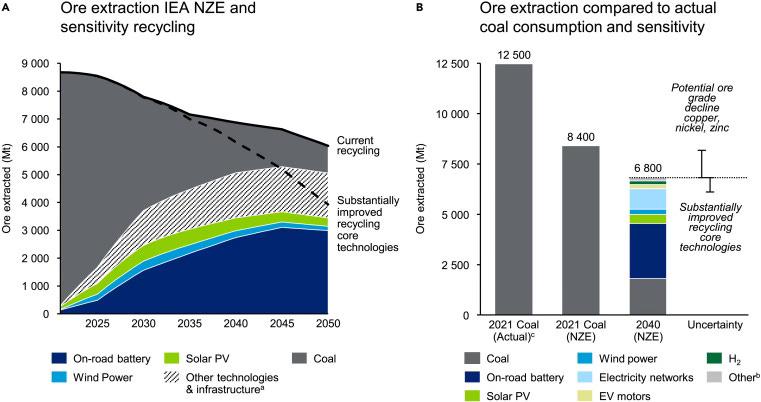

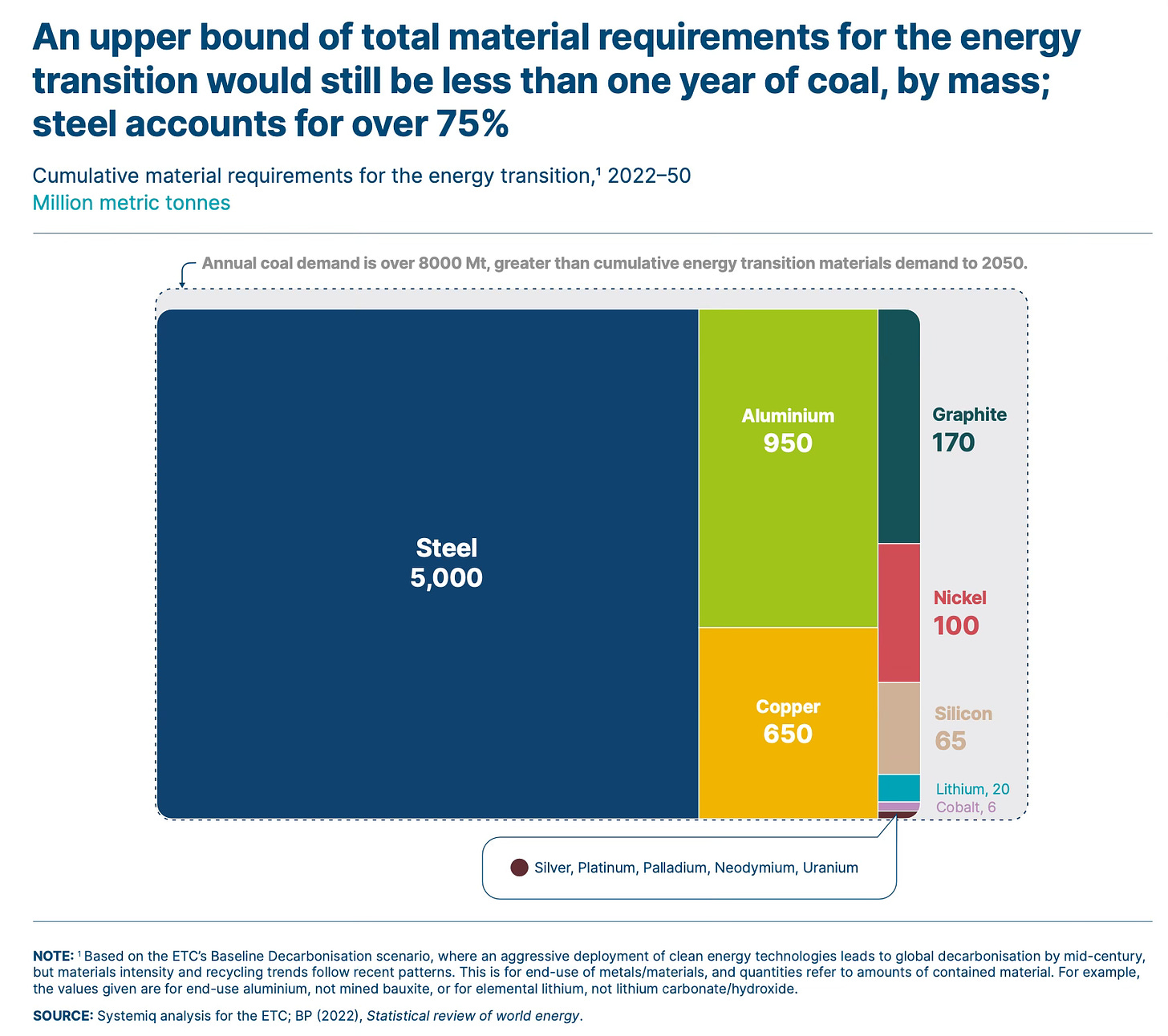

So, how does one square this with a few interesting papers which seem, on the face of it, to be suggesting precisely the opposite thing? Among the most prominent was this recent paper by Joey Nijnens and others. The paper looks at the total amount of material requirements for the energy transition and compares them with our current fossil fuel use.

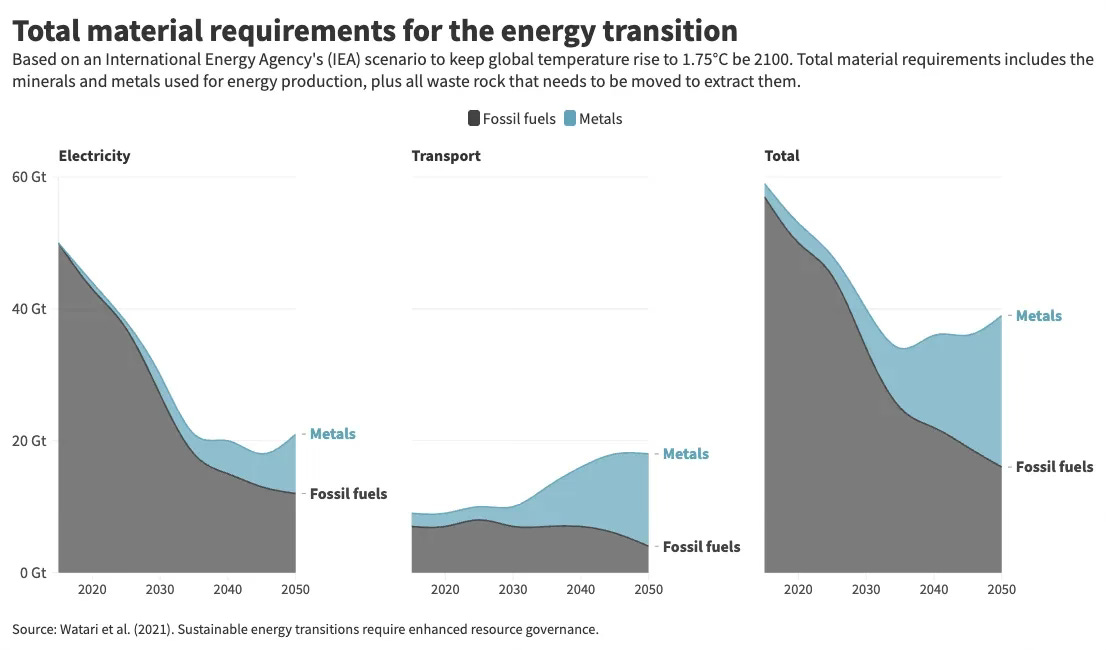

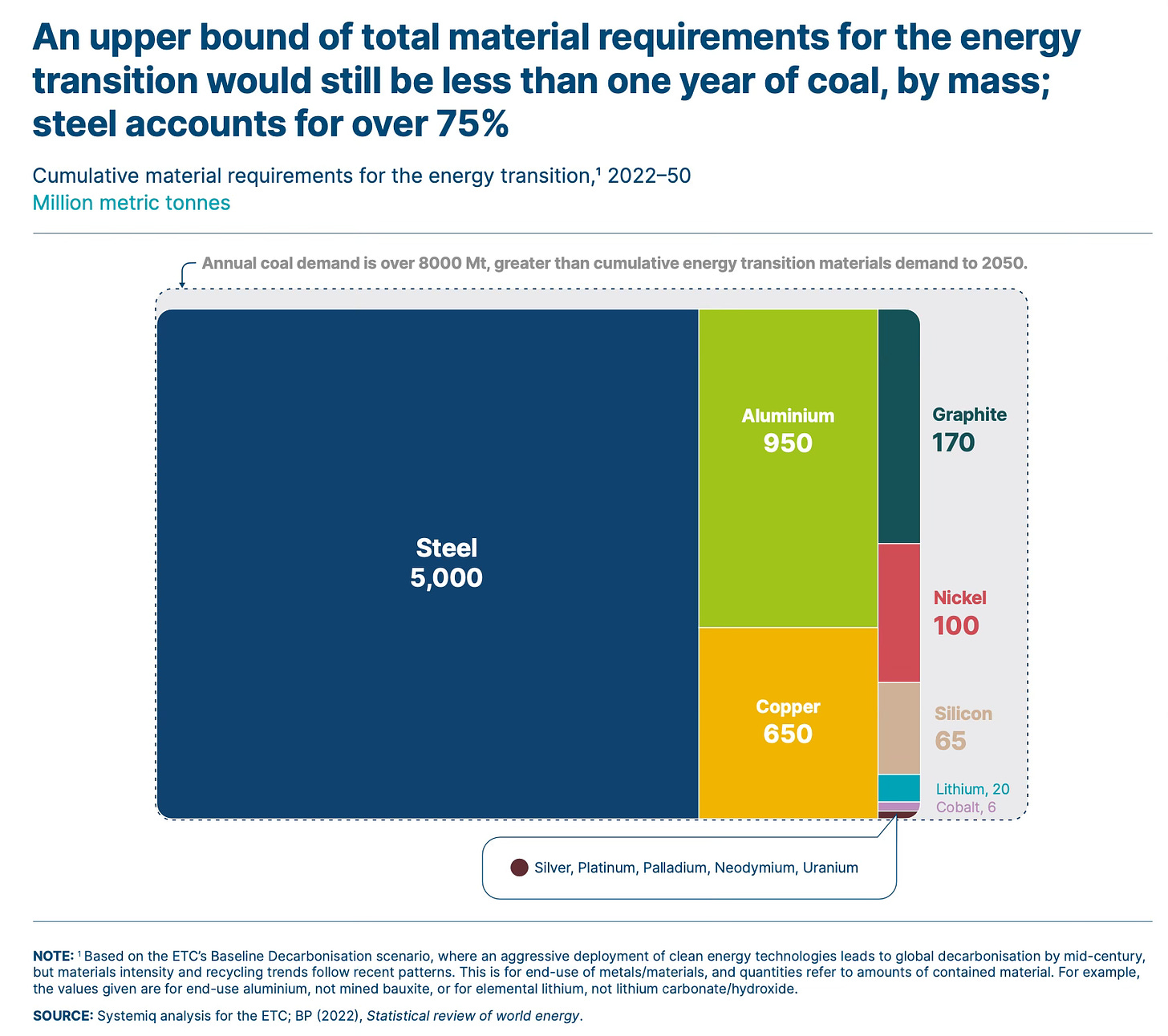

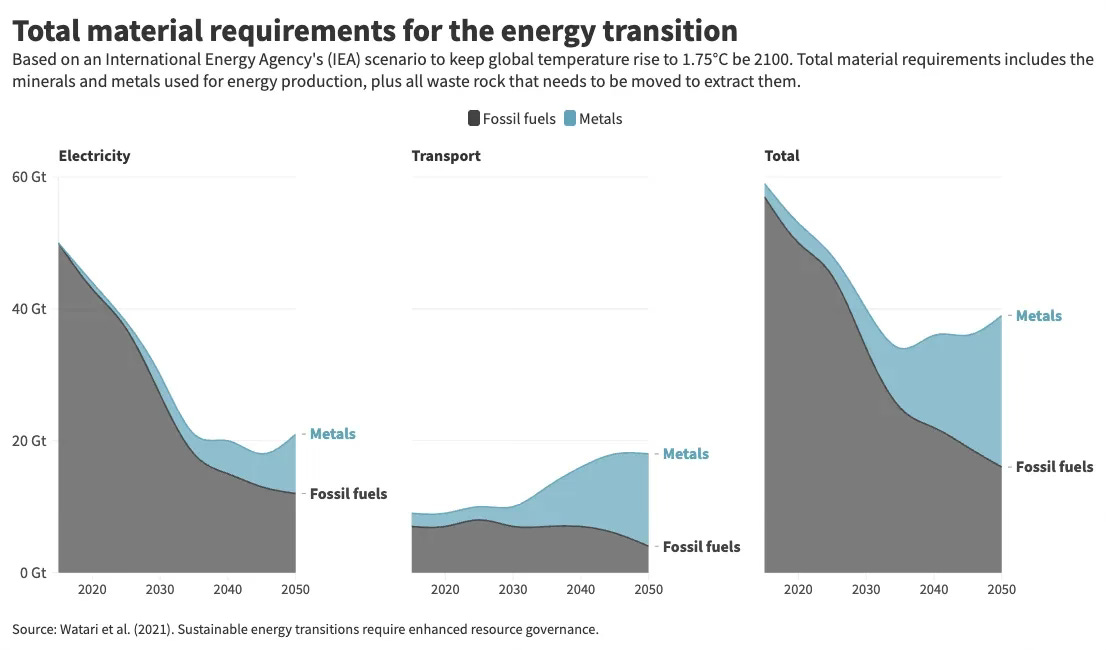

The charts underline an important point. We use an extraordinary amount of fossil fuels each year (far, far more than most people appreciate). And the main message from this chart is that while we’ll certainly need to do a lot of mining to get the copper, lithium, cobalt etc we’ll need, that weight of “new” stuff will be far less than the weight of all the fossil fuels we’re no longer using.

But the chart, which begins at around 2020, seems to suggest that this is happening now.

In other words, far from increasing in the short to medium term, as I wrote in my book, it looks tantalisingly as if humanity’s material footprint is actually about to fall immediately.

Hannah Ritchie did an excellent post a few weeks ago on that paper and another one making a similar point. As you’ll see from her chart (based on the data in the other paper, this one from Takuma Watari et al), the shape of the line is quite similar:

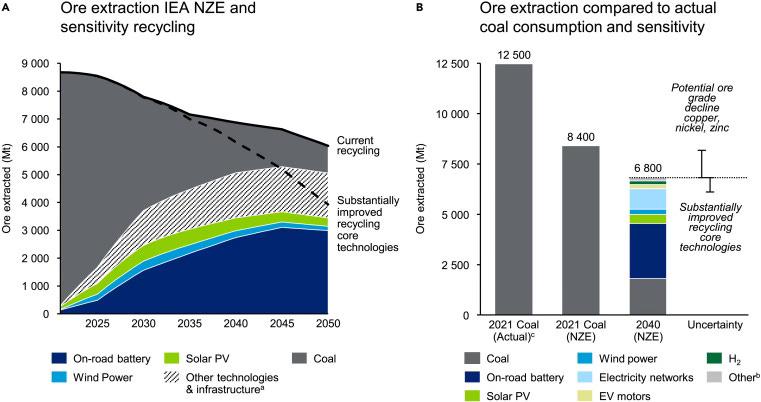

On the basis of all these charts it looks as if our mineral demand has already peaked, and that it will fall on a more or less constant basis in the coming years. Indeed, if we improve our ability to recycle then the line goes down even faster, so that by 2050 our apparent footprint has diminished considerably.

But is this really plausible? In other words, might things have improved so rapidly since I wrote those words above that I am already wrong - that far from growing, our footprint is about to shrink?

Unfortunately, the answer is no, for two reasons.

The first, and by far the most important, is that the charts above are based not on a realistic forecast for where our mineral consumption may actually head in the coming decades, but a very ambitious pathway we are already short of.

You see, the charts above are predicated on the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Emissions (NZE) pathway.

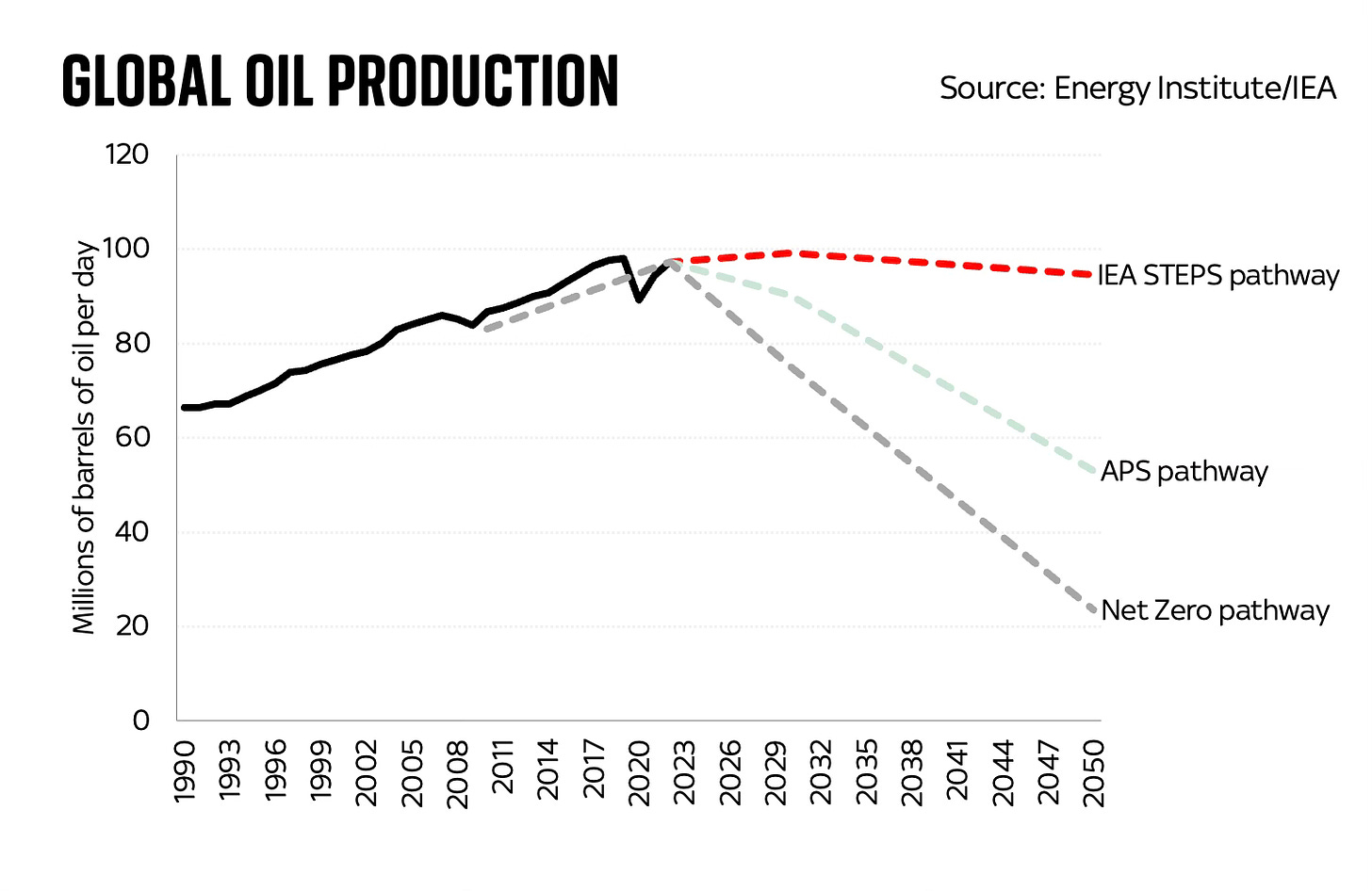

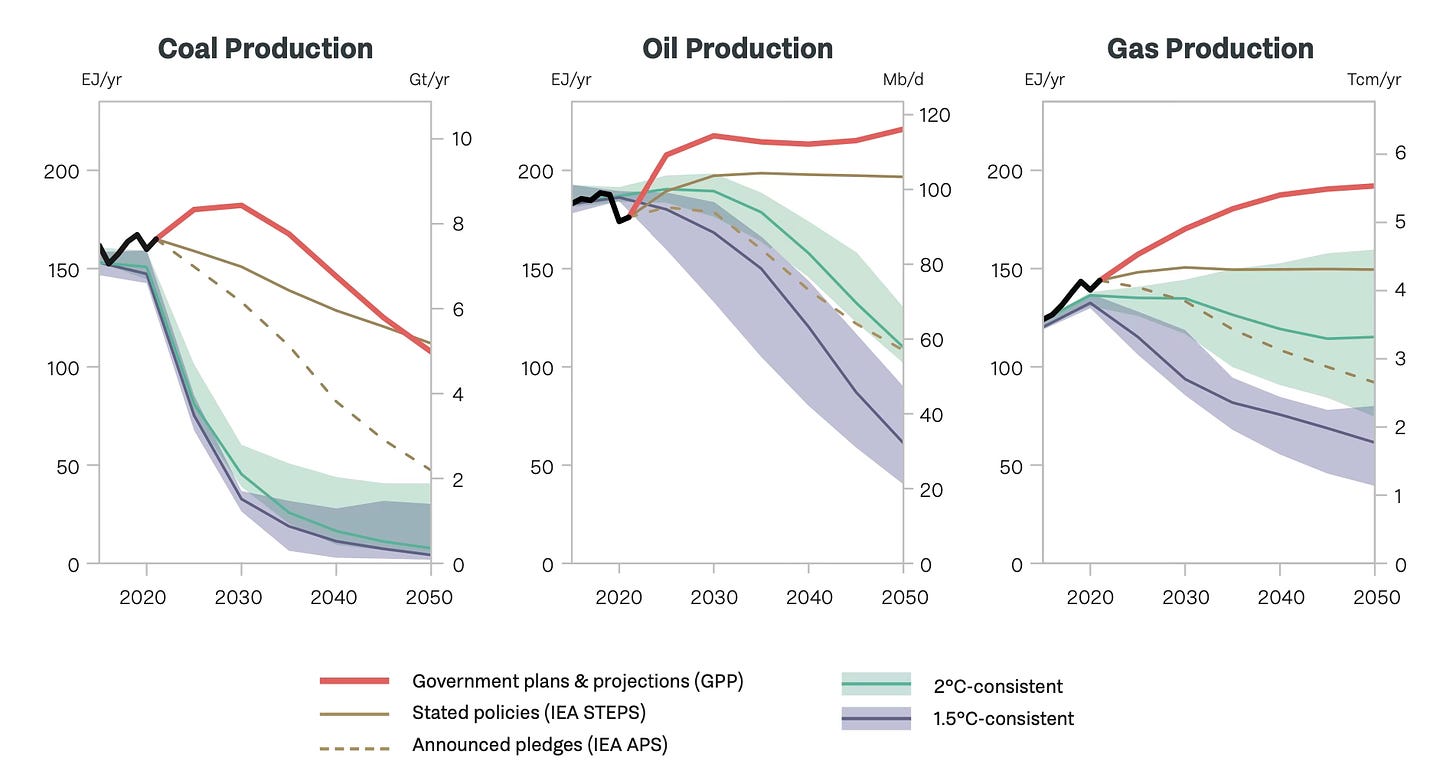

Long story short, a couple of years ago the IEA produced an excellent report providing a roadmap for how we might be able to get to net zero across the world. Actually they provided three roadmaps: a very ambitious pathway which could actually get the world to net zero by 2050 (the NZE pathway), as well as two other routes - one based on “announced pledges” (APS) - what governments said they would do and “stated policies” (STEPS), which is, for want of a better phrase, “business as usual”.

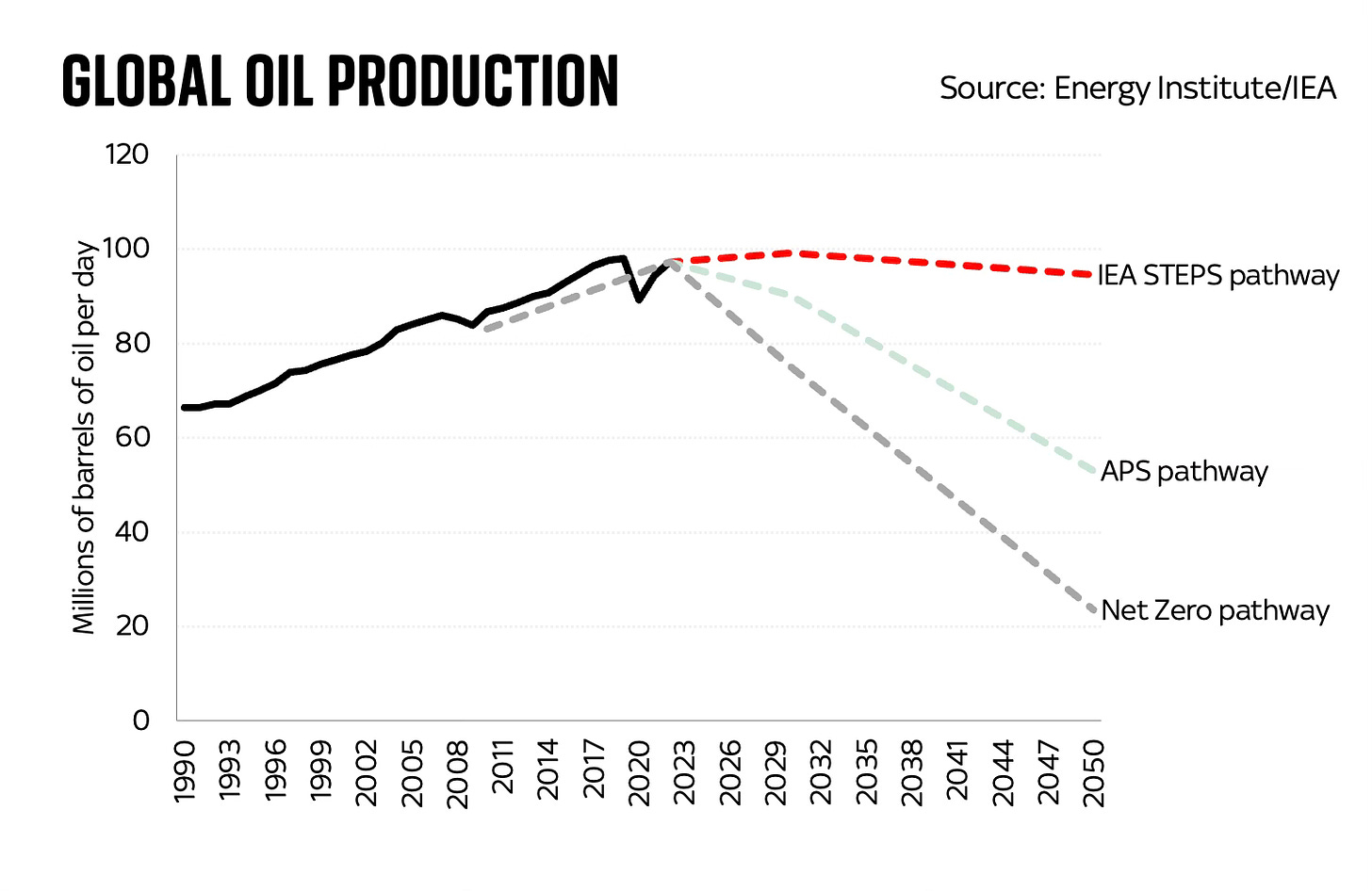

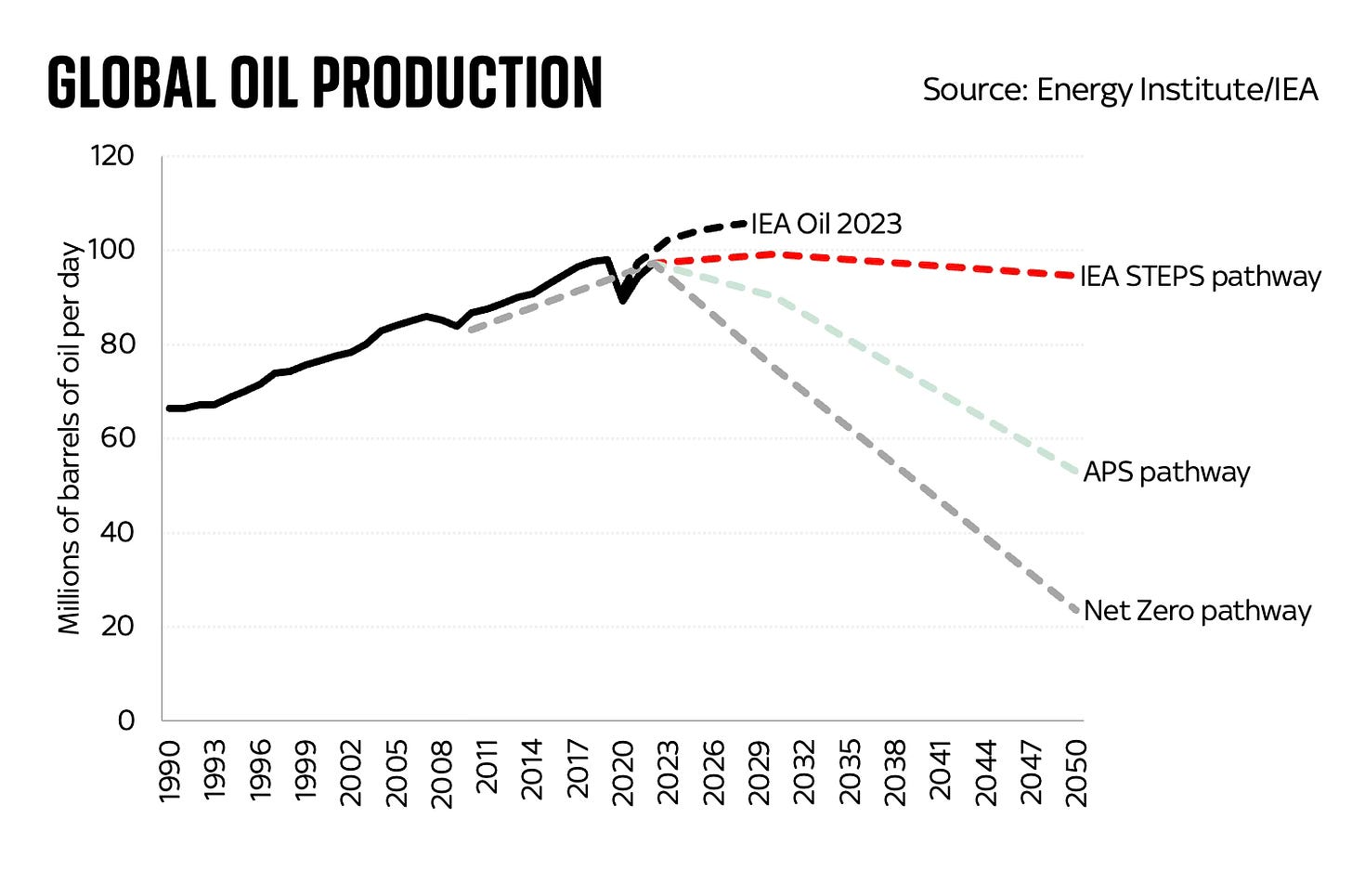

You get a sense of the difference between these pathways when you look at the chart above, in which I’ve mapped out what each of these IEA pathways assumes about crude oil production. The net zero pathway involves a very quick fall in global oil production in the coming years. But the other two pathways see oil production fall far more slowly (and, by extension, we fail to keep global temperatures below the 1.5 degree threshold).

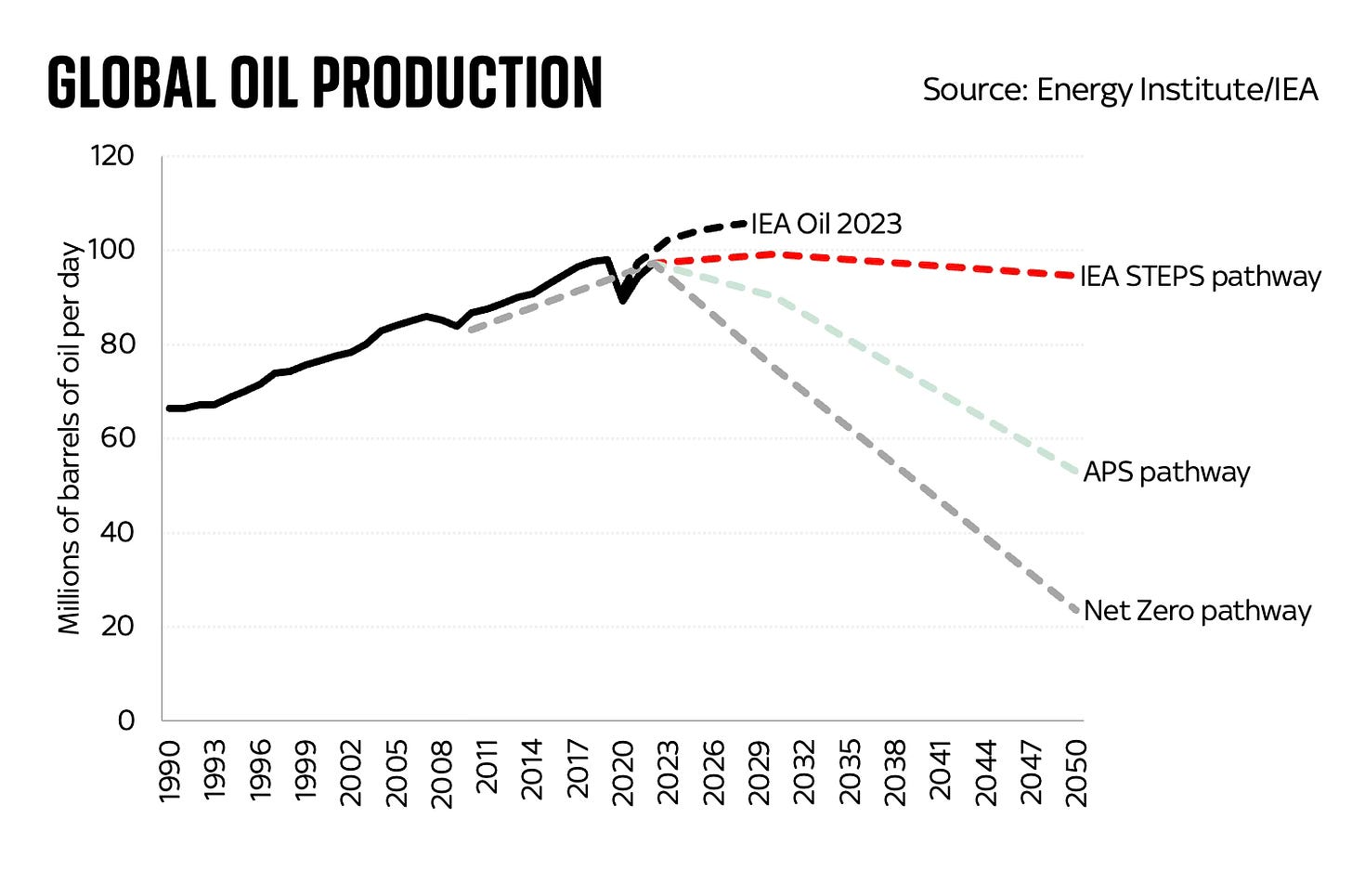

Now let’s look at where the IEA thinks, on the basis of its latest assessment of what’s actually happening in the oil market, production is and is likely to head in the coming years. I’ve added another line to the chart:

You probably already get the picture. Far from following the net zero pathway, we are already some way short of it. Actually it’s worse than that: oil consumption is likely to overshoot all of those pathways in the coming years.

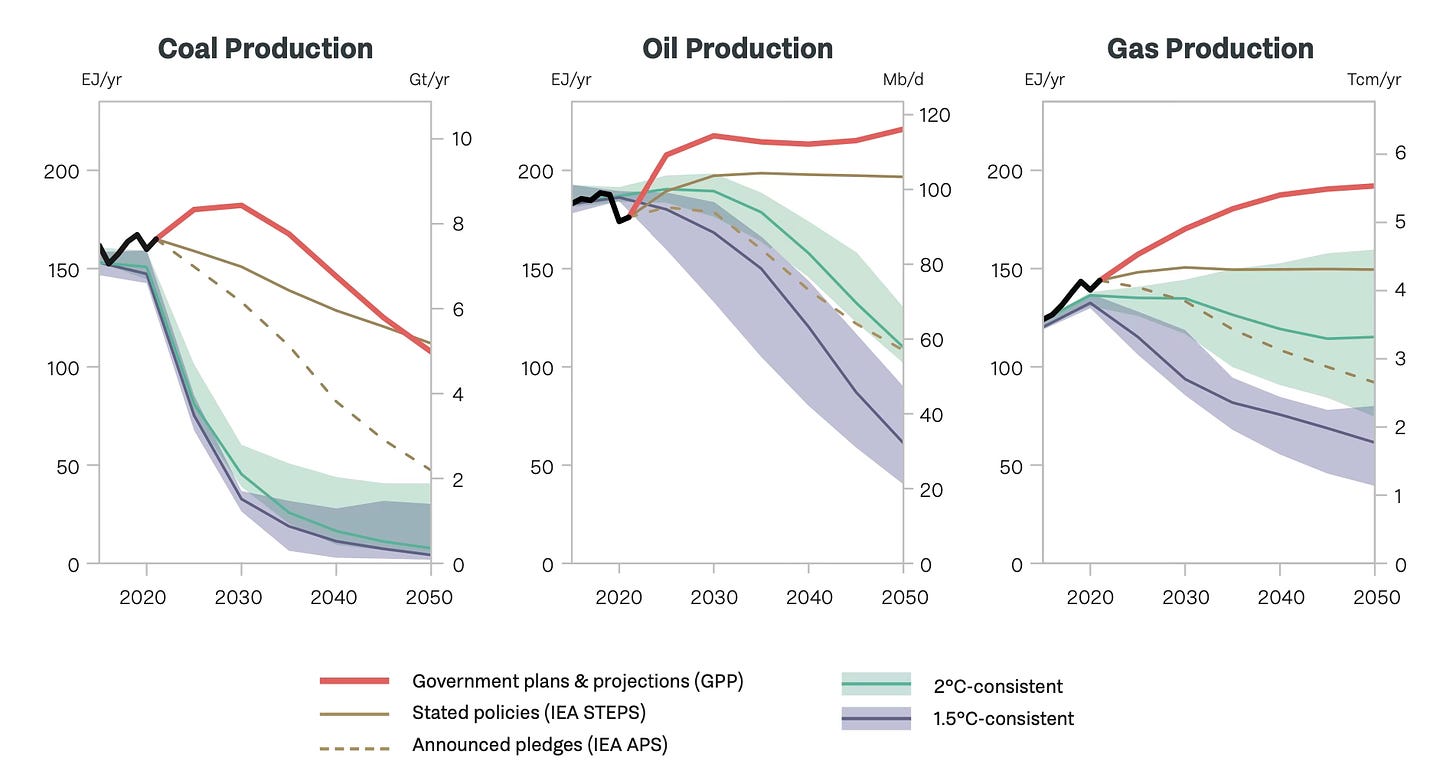

This, by the way, is precisely the story told by another recent report, the UN Production Gap 2023 report, which compares some of these pathways with where it actually looks, based on what fossil fuel producers are doing, where we’re heading. Look at the difference between the red lines below and, well, pretty much all the other lines.

You see, on the basis of revealed preference - what fossil producers are actually doing as opposed to what the IEA and others would rather like them to do - those lines aren’t going down in the coming years. They are rising, and in the case of oil and gas they may be considerably higher in 2050 than they are today. Coal production also just hit a record high in 2023.

Now, I suspect and also rather hope that the reality turns out to be considerably lower than those red lines. But what this exercise does is to underline that far from falling in line with the IEA’s best case scenario, right now fossil fuel use is rising above even its worst case scenario.

So any papers looking at future minerals demand and basing it on the IEA’s net zero scenario must be regarded not as exercises in prediction but as interesting thought experiments. Which, in fairness to these papers, is precisely what they are. And they make an important point: that in due course the energy transition should be far less mineral-intensive than today’s fossil fuel era. But the timing implied by those charts is way off.

Now, it’s worth saying, in the supplementary material to their paper, Nijnens et al say that if the world followed the STEPS scenario (eg the IEA’s worst case scenario) then:

“The estimate for 2040 ROM coal and ore extraction in the STEPS scenario is 8470 Mt, a similar extraction to the 2021 NZE ROM coal and ore extraction calculated in this research.”

In other words (and bear in mind this is based on a scenario which we’re already overshooting), our footprint will increase and then plateau before it decreases. And that decrease won’t begin for a while. There will, in other words, be a hump.

Once we get over that hump, the footprint does indeed start to shrink as the dynamics mapped in these papers suggest. As I wrote in the book, squint a bit and you can envisage a future where:

The world will be a healthier, more productive place, with fewer deaths from pollution, and since we will mine far fewer fossil fuels than today, our footprint will genuinely have shrunk across the world.

And for further excellent infographics about the sheer difference in scale between fossil fuel mining and future mining for green energy infrastructure (including stuff like steel), there’s a great recent report from the Energy Transitions Commission. With charts like this one:

But while this might be the case in the future, it’s not going to be the case for quite some time.

And that hump, like it or not, is probably what we’re heading for in the coming years. Those charts at the top are, like the IEA’s net zero model, better thought of as wishful thinking.

That brings us to a broader point, one recently made by the excellent Rob West of Thunder Said Energy: it’s very important to distinguish between the many models of what could constitute a plausible pathway to net zero and the pathway we’re actually on. None of this is to deny that these models are useful guides to how we might be able to shift towards cleaner energy: but they’re what they are. They’re models.

Rob’s own models, while we’re at it, suggest there will indeed be a peak (or maybe better to call it a plateau) for our material consumption around 2030, mostly thanks to a fall in global coal consumption. But his chart - the one above - is very different indeed to the ones at the top. For one thing, it has that hump.

Anyway, all of this is before you consider the other proviso which has to be appended to the analysis in these papers, which is that they aren’t considering all of the materials.

As you’ll know if you’ve read the book or indeed some of my previous blogs, the majority of our planetary footprint isn’t metals or fossil fuels, but the sands and aggregates and stone we dig and blast out of the earth’s surface to provide us with construction materials. It’s concrete; it’s sand used for land reclamation; it’s the aggregates we use to pave our roads.

And frankly there’s little sign of our consumption of that kind of stuff falling any time soon.

It would have been nice to have ended 2023 by declaring that we had reached the point of “peak stuff” - as those charts at the top seem to imply. But the reality is very different.

Our mineral consumption isn’t about to fall. We’re heading for the hump.

I read The Techno-Optimist Manifesto so you don’t have to. Rintrah by Radagast. Dec 2, 2023

There’s a growing realization I have, that one of the main effects that wealth and technology have is their ability to shield the mind from reality. Opulence is an insulator. More than anything, opulence makes you feel invulnerable. In Uganda, men prey for rain. They understand that they are tied to their environment and its well-being.

This doesn’t really exist in the modern world. You don’t feel tied to your region. I would encourage you to ask people, why they live where they live. Ask someone: Why do you live in Rotterdam? Why do you live in St. Louis? Why do you live in Maastricht? Why do you live in Memphis? You’ll receive answers like:

“Well because I want to study engineering”

“Because I work at an auto manufacturing plant”

“Because my parents moved here”

I can almost guarantee you there’s one thing nobody will say: Because there’s a river. And yet that’s probably why you live where you live. All the answers you will give come back to that point. Your grandfather moved to Chicago to work at a steel mill? Oh cool. So why is the steel mill there? BECAUSE THERE’S A MASSIVE RIVER LEADING TO NEW ORLEANS, ALLOWING YOU TO SHIP HEAVY GOODS ACROSS THE COUNTRY AT A FRACTION OF THE COST OF TRANSPORTING THEM BY ROAD OR RAIL.

And everything else you’re doing, only exists by the grace of these industries. You don’t work at the steel mill in Chicago, but at a university in Chicago? Well congratulations, you’re even further removed from actual physical reality, making you even more blind.

If you see the coal brought in by boat, or the finished product leave by boat, you might at least once in your entire life remember why you live where you live. But if your job consists of explaining to a bunch of 18 year olds why everything is racist, sexist and/or homophobic, you are permanently protected from understanding how you ended up there. Your entire reality is social, so you end up understanding nothing.

A lot of people have this back to the land fantasy. It’s easy to discover this, when you point out how harmful SUVs are. You’ll discover numerous Americans who insist they need one, to drive back and forth to their permaculture farm somewhere in bumfuck nowhere. In reality, we would be better off with people moving “back to the water” instead of “back to the land”.

I think it is this isolation from the reality of nature, that makes it so difficult for most people to accept that environmental problems are real problems. You can get people in Uganda to understand that climate change is a real problem. You can’t get most Western men to understand it, because technology serves to completely insulate them from reality. When things go wrong, there’s supposed to always be a technological solution for them. The scariest idea to them, is the idea that there are just certain limits you’ll need to respect.

Because billionaires in the United States tend to get rich by embracing technological progress, they tend to feel personally attacked by the idea that technological progress is running into hard limits and is increasingly unable to make life better for the majority of our population. It’s similar to trying to explain the energy problem that Bitcoin has, to someone who became rich through Bitcoin.

There are some billionaires who seem at least somewhat aware of this problem. Ted Turner is notorious for warning about the overpopulation problem. Bill Gates is pretty worried too. He realizes it’s going to take a long time, to solve the climate problem. Hence he wants to block the sun, which angers low IQ low status white males, who would prefer to die in their mobile homes when their air conditioning stops working.

But others are less worried. Others are worried, about our worries. That includes Marc Andreessen. So before I start off reviewing the manifesto he wrote, I want to point out how Andreessen became rich. Andreessen has worked for tech companies for a long time, but in 2009 he founded Andreessen Horowitz with his longtime business partner Ben Horowitz. He started out investing in various software companies.

These companies, as you may know, can reach ridiculous valuations. What Andreessen Horowitz do, is that they enter bubbles before they form. This is why they’re so enthusiastic about cryptocurrency. They invested in Ripple, in Coinbase, in cryptokitties, even in various obscure cryptocurrencies. The advantage this has is that they’re then rewarded with tokens, which they’re legally allowed to dump onto low status white males who fall for these swindles, as these are not securities.

This is basically the Andreessen Horowitz strategy: Ignite a forest fire and then sell it as a heat generating machine. High status white males like Andreessen set up businesses that sell shovels and then they wait for low status white males to go dig for gold. But this business is coming to an end, as low status white males are now stuck with credit card debt and have no money left to buy fake shovels and fake Internet gold from high status white males like Andreessen.

You know the situation is dire, because in the past when you used to point out that these are all scams, a low status white male would immediately appear from thin air, who would argue that every cryptocurrency is a scam, except for his own variety of fake internet money. These days you don’t even really see those types anymore.

So these dudes are in trouble. They don’t make money by funding things that people use. They make their money by investing in things before the dumb herd is able to invest in them. They don’t really care what they invest in, as long as the dumb herd shows up afterwards. But that dumb herd is running out of money.

I think this is some important context to the manifesto. You have a billionaire who moves onto increasingly more speculative ventures, pouring money into them in anticipation of the LSWMs who will show up later to inflate the value of those ventures. I think this man is trying to convince himself that his investments still make the world a better place.

So now onto the manifesto. Starting out with the good, the manifesto makes me feel less cringe. It isn’t any better or worse than something I would write for this blog while home alone on a Friday night. Example:

We believe that we are, have been, and will always be the masters of technology, not mastered by technology. Victim mentality is a curse in every domain of life, including in our relationship with technology – both unnecessary and self-defeating. We are not victims, we are conquerors.

We believe in nature, but we also believe in overcoming nature. We are not primitives, cowering in fear of the lightning bolt. We are the apex predator; the lightning works for us.

You can be a fifty-something year old billionaire and still just write like an angsty objectivist teenage boy.

We all know by now, that when someone writes a book to debunk an idea, it’s because she fears the idea is true. And similarly, when someone writes a manifesto, it’s intended to convince himself of an attitude towards life he no longer believes in. If Ted Kaczynski really believed life in his cabin in Montana was idyllic, he wouldn’t spend his days blowing people up and writing his manifesto.

Let us look at the Techno-Optimist Manifesto again. I had expected it to be somewhat nuanced, to incorporate and then reject the critiques of eternal growth many smart people with far less money have already offered. Consider:

We believe energy should be in an upward spiral. Energy is the foundational engine of our civilization. The more energy we have, the more people we can have, and the better everyone’s lives can be. We should raise everyone to the energy consumption level we have, then increase our energy 1,000x, then raise everyone else’s energy 1,000x as well.

The European Union has reduction in energy use as one of its official goals, because we already know this can’t work. Energy is ultimately heat. When we use more energy, we warm up our environment. That’s one of the reasons cities are warmer than the countryside.

After about 400 years of perpetual growth in energy consumption at 2.3% a year, the Earth’s surface would reach boiling point. This is just basic stuff you would expect people to know, but he either doesn’t know it, or he’s just sticking his fingers in his ears like a toddler and going “LALALALA I CAN’T HEAR YOU”, because he goes on to say:

We believe energy need not expand to the detriment of the natural environment. We have the silver bullet for virtually unlimited zero-emissions energy today – nuclear fission. In 1973, President Richard Nixon called for Project Independence, the construction of 1,000 nuclear power plants by the year 2000, to achieve complete US energy independence. Nixon was right; we didn’t build the plants then, but we can now, anytime we decide we want to.

The mysterious thing about the techno-optimists is that whenever they see us not doing what they want to do, they assume it must be because we just don’t want it. They never think to themselves “well, perhaps it wasn’t possible after all”.

Consider the nuclear delirium, the insanity that right wingers are peddling now that they’re ever so slowly coming to terms with the fact that yes, we’re rapidly making most of the planet inhospitable to human civilization. Now they have a solution: The whole thing could work, if we simply built nuclear power plants!

This is not a new solution, mind you, nor is the delirious optimism new. In the 70’s the Dutch prime minister sold all our natural gas for pennies, because they assumed it would be worthless and left in the ground as we would soon all be using nuclear energy instead. Today we’re stuck with the hangover from the naive optimism of our parents and grandparents.

There isn’t really a place on Earth, where we see what these people want to have. Not in communist China, not in Japan, not in the former Soviet Union, not in the US of A, not in South Korea, not in Taiwan, there’s no place on Earth that runs on nuclear. The sole exception you could argue is France, but that country depends on the rest of Europe to export and import its electricity, because their reactors have to shut down in summer when the rivers get too warm.

The reason it didn’t happen of course is because you run into scaling problems everywhere. It takes time and experienced crews to build these reactors, the reactors themselves depend on rare minerals, you need special locations near a source of water, away from dense cities and not at risk of war or natural disasters and then eventually you need to figure out a location to dump the waste. The reason the United States didn’t build those 1,000 reactors before the year 2000 is because it can’t.

But the biggest problem, is a problem I already touched on at the start of this post: Water. Everything ultimately depends on water.

What does a nuclear reactor do? It releases heat by splitting atoms, which we then use to generate movement in water and thereby ultimately produce electricity. This releases huge amounts of new heat you’ll need to leave somewhere.

Humans feel very powerful and in control, when they split the atom. But what do you do with the heat that you produce? Where do you leave it? Well, for 95% of all nuclear power generated we decide to cool our reactors with water.

So, we dump that heat into our water supply. If you warm up the water next to your shore, you’re going to produce toxic algae blooms, because the water stops mixing properly and you reduce the influx of oxygen. That means the fish in that environment eat toxic algae, causing the build up of domoic acid. This causes brain damage. Take a look at this:

A rash of attacks by seals on humans in South Africa has been blamed on brain damage caused by diseased fish.

A “red tide” of toxic algae, boosted by climate change, has found its way into South Africa’s seal population through the fish they eat.

That’s caused a mass die-off of seals – but those that remain have become unusually aggressive.

Can nuclear energy reduce our CO2 emissions? Probably. But we want to reduce our CO2 emissions, because we want less heat in our environment. If we build nuclear energy power plants, we move from increasing global warming, to increasing local warming. That’s not better, that’s worse.

Around 95% of all nuclear power generation uses water as a coolant. There are alternatives, there are a handful of gas cooled nuclear reactors. But if you want to have a nuclear meltdown, the best way to achieve it is probably to use an obscure type of reactor with a coolant that just disappears into the atmosphere as soon as something breaks. And it’s inevitably more expensive too.

A nuclear power plant is allowed to dump water into our seas and our rivers, that is up to six degree warmer than the water it took in. Do you think I want to cause six degree of local warming in my local water, to reduce global warming by less than 0.01 degree Celsius? That is suicidal.

And more importantly it doesn’t work either. Nuclear energy is intermittent energy. When the local water gets too warm, you can’t dump your water back into the environment. Sweden had to shut down one of its nuclear reactors in the summer of 2018, because the water got too warm. Climate change has the nasty habit of making proposed climate change solutions obsolete.

If the water is getting too warm for Swedish nuclear reactors in 2018, what do you think will happen to Dutch nuclear reactors that we want to start building today, that won’t become operational in 2030? They will cease offering any electricity during summer at all!

But these people don’t want to hear this, because they’re invested in the myth of mankind mastering nature. Not the individual man making it through the merciless Alaskan winter or anything like that mind you. These are not genuine rugged individualists, they are collectivists at heart, like most people. The autists and schizoids, the natural individualists, are rare creatures indeed.

No, Mankind is going to master nature, colonize other planets without atmospheres and figure out some way not to die of space radiation while doing so. So in the Techno-Optimist Manifesto we find Andreessen arguing that “the ultimate mission of technology is to advance life both on Earth and in the stars”.

Note that these people are also never really interested in a consolation price. They don’t speak of building floating cities on the ocean. They don’t speak of colonizing Antarctica. They’re not interesting in building domed underwater cities on the bottom of the ocean floor.

These are all vastly more cost-effective and realistic scenarios than colonizing Mars, or worse, places outside our solar system. It something goes wrong, you can send assistance within hours, instead of months. You have an atmosphere protecting you from harmful radiation. There would be a meaningful economic purpose to pursue.

But nobody is volunteering for this. Nobody is volunteering to live in a city 4000 meter beneath sea level. Nobody is pushing governments to let them build a city in Antarctica. Even the simplest possible option, a floating city, has hardly anyone genuinely interested. When you have 10,000 people living on a floating city, that is self-sufficient in food production, you can begin to think about more ambitious projects.

Keep in mind, these are all opportunities that would have a realistic chance to achieve what the Mars colonization enthusiasts claim to pursue: Protect humanity from extinction. When by 2100, most of the world gets too hot for human survival from time to time, we will still be right in the middle of the release of various greenhouse gasses from natural ecosystems.

What would probably help humanity survive by then, is if we had functional cities in Antarctica, floating cities on the ocean that could be moved to the North Pole or deep underwater cities shielded against above-ground temperatures (and against nuclear fallout). Those would all increase our survival chances as a species. Oceanic cities near the North Pole would even have an additional benefit: They would repair our climate by reflecting sunlight.

Colonies on Mars don’t have any of these benefits. They would inevitably just be an economic drain on planet Earth, unless you think a colony of 400 settlers on Mars would just 3D print their own CT scanners, dialysis machines, the rare earth minerals that go into such machines, antibiotics, pesticides (assuming they don’t just keep importing all food), baby milk powder, tetanus vaccines, radioactive iodine when someone gets sick, birth control pills and anything else humans need eventually. We’re able to have our standard of living, because we live around billions of other people who can deliver us anything we need, most of it within hours.

The actual reason the richest man on the planet wants to colonize Mars of course, is because reality doesn’t matter anymore for making money, as we don’t live in a society that punishes failure. We reward people who show us an image of success. In such a society, you become rich by telling people what they want to hear. You package people’s hopes and dreams and sell them back to them at inflated prices.

The reason this annoys me so much is because there are a handful of people out there who do accept that limits to growth are real and are working on solutions that could allow us to have something resembling a future. These solutions are humble and the people who propose them don’t have loud mouths, so you never hear about them, while the billions continue to flow to guys like Andreessen and Musk, who promise you a future on Mars.

It’s possible to grow seaweed in the ocean, ship it to shore by sailboat, dry it on land, burn it in a thermal power plant and then sequester the CO2 underground. This is a way to sequester CO2. It’s also possible to mine olivine, disperse it on beaches and let the mineral sequester CO2 for us. It’s even possible to bring the air to very low temperatures, until you eventually have frozen CO2, which you can then bury somewhere. A plant built for this purpose on Antarctica would be most cost-effective.

But again, there’s no true interest in ambitious projects. There’s a crisis of meaning, which people like Musk and Andreessen jump into with increasingly ridiculous ideas and visions for the future.

To a large degree, Andreessen’s success can be traced to him saying “Fuck ESG”. In the manifesto he makes this explicit. He writes:

Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades – against technology and against life – under varying names like “existential risk”, “sustainability”, “ESG”, “Sustainable Development Goals”, “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management”, “de-growth”, “the limits of growth”.

If everyone else managing large sums of money is worried about making sure they don’t make the planet uninhabitable while adding another zero, but you decide not to worry about that, you have a strategic advantage. But when you use that strategic advantage, you want to justify it to yourself.

And so, you come to believe in “overcoming nature”, rather than in respecting nature’s boundaries. This doesn’t work. It just makes the eventual terms of surrender worse. If people had understood this simple principle, they would not have done something so stupid as attempting to vaccinate the whole world against a rapidly mutating SARS virus either.

But sadly, the Andreessens of this world don’t understand this. This means they are setting mankind up for just one possible outcome: Unconditional surrender.

Am I an Alarmist? "Sarah Connor", Collapse 2050.

Maybe I'm the one that's a fool. Do these people know something I don't know? Am I wrong to think human civilization is circling the drain?

I never share my articles on LinkedIn.

LinkedIn is a circle-jerk of blind corporate optimism and virtue signaling. Between pointless meetings, political finagling and pseudo-intellectualism, there's no way these corporate vine-swingers want to hear that their very reason for existing is soon coming to an end.

Despite superficialities, many of these people are actually quite smart. But perhaps not smart enough to redirect their energy to something useful.

Who knows. Maybe I'm the one that's a fool. Do these people know something I don't know? Am I wrong to think human civilization is circling the drain?

Or, perhaps my assessment of the problem is correct but the techno-optimists are right that we'll eventually be saved by human ingenuity.

I wonder if I'm an alarmist.

I've always been this way. I picked up my anxiety from experience and my family. When was a small child I worried about war, destitution and the cruel world. As my consciousness matured during the height of the cold war, I fully expected to get nuked at any moment. That eventually wound down, but my existential angst violently resurfaced in 2001 when I learned about peak oil and the Olduvai Theory.

Meanwhile, the world was getting peppered with financial and medical calamities. Is it any wonder why I peer around the corner for the next disaster?

Yet, there are many others that are optimistic about the future and human ingenuity. Some even believe developments in AI will thrust humanity to a new era of abundance.

I wonder if I'm projecting my own anxieties onto my outlook for humanity. After all, there are plenty of other people who are equally convinced that I'm wrong.

Here's the thing. If I'm wrong, that would be the best possible outcome. I hope I'm wrong about our dystopian future. Just as I hope I don't crash next time I ride in a car.

Did you know: For every 1000 miles you drive, your chances of getting into a car accident are 1 in 366. That's lower than 1%, yet that doesn't stop me from wearing my seatbelt. I think most people do the same. However, decades ago it was considered alarmist to suggest people wear seatbelts. It became a debate over freedom. Some even argued it was safer to get thrown from a car during an accident.

If one feels the need to prepare for a car crash it certainly makes sense to prepare for crop failures, mass migration and broken supply chains.

Let's say there's only a 1% chance human civilization is wiped out. Even with such a low probability, the downside remains too great to ignore the possibility. People must prepare. I pulled the alarm, not because I'm an alarmist but because I want to warn people of what might be coming. If more people were alarmed, we might actually do something about it, reducing the cause for alarm in the first place.

With that said, I think the probability of civilizational collapse is much greater than 1%. There's a near certainty of collapse.

I've seen the research. Watched the trends. I've even observed the changes first-hand. The implications of a hotter climate - heat deaths, lower crop yields, rising seas - are obvious. The greenhouse effect has been known for about 200 years. Exxon itself forecasted everything we're seeing.

The big question is when and how?

Still, I must leave room for the possibility I'm missing something. Or that I'm underestimating human ingenuity, adaptability and technological advancement.

However, if I look at the evidence laid out in front of me, my predictions are well-supported by observable facts. Meanwhile, the counter argument is founded on unproven technologies and the crude extrapolation that civilization will continue to exist because it currently exists. The optimistic view is built on survivorship bias.

Unfortunately, the ghosts of failed past civilizations don't get a voice. If they did, there'd be a lot more alarmists.